The Watery Way

Sally Bonn

A thunderstorm. Night. Water runs down the walls, onto the windowsills, it runs from the roofs, down the façades, down the sides, on the bas-reliefs, the columns, the pilasters, it runs inside, too, down the bookshelves, it soaks the books.

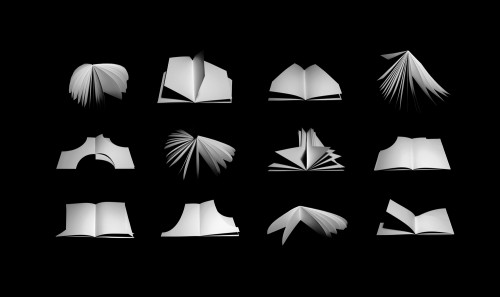

The child, the poet, watches the water and hides. At dawn, the books are stacked in piles on the bare ground and topped with a heavy stone that compresses them, squeezing them like sponges. Frothy, foamy water escapes from between their pages.

“Books must be well kept and read, for books are Soul and Life. Without books, the world would have witnessed nothing but ignorance.” And so the books are carried up onto the flat-stone roofs, one by one, and opened to the air and sun to dry. The pages turn in the wind around the future poet who stretches out among books that dwarf him in the faint sound of suspended phrases. The child who will become poet and who lies down among the open books is the man whose life and soul are torment. His name is Harutyun Sayatyan, he was born in Georgia in the early 18th century. The filmmaker Sergei Parajanov traces his life in the fascinating visual poem The Colour of Pomegranates. For the poet Sayat Nova, there are three holy aims: to love the pen, to love writing, to love books. The artist listened to Sayat Nova’s song.

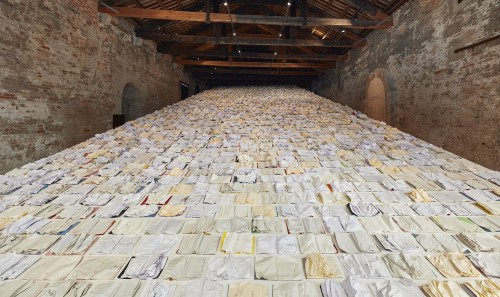

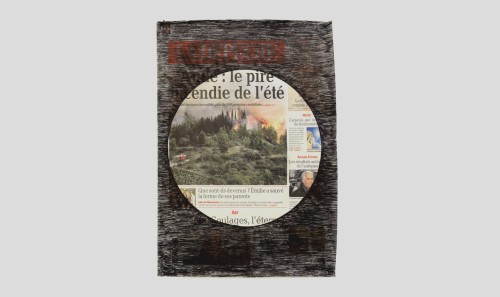

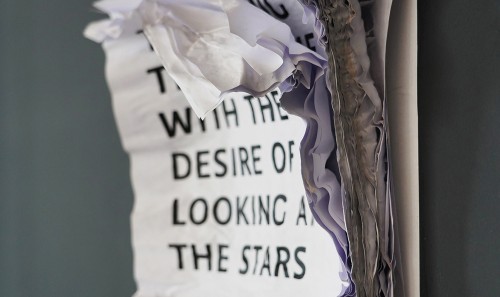

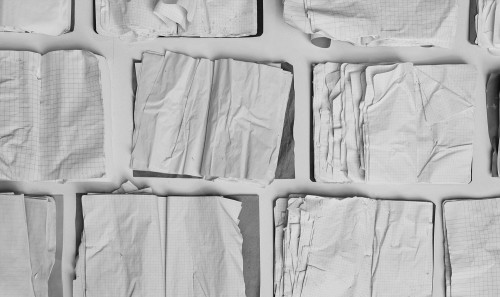

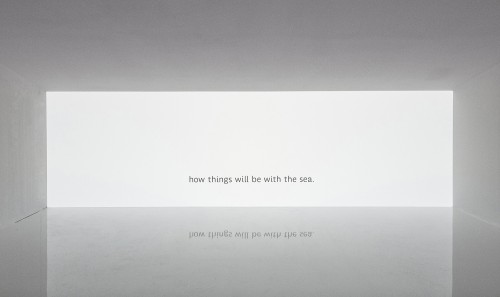

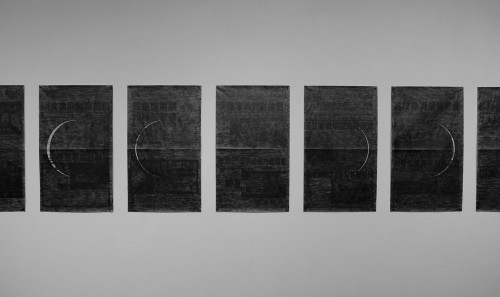

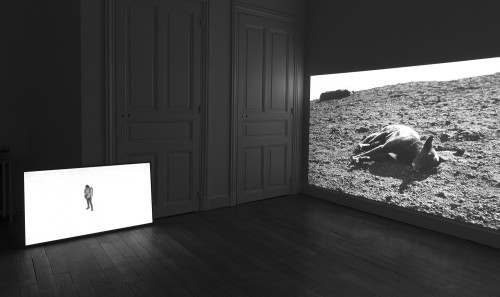

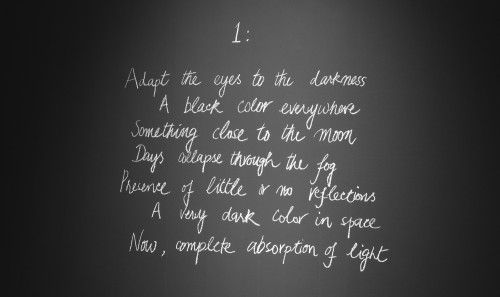

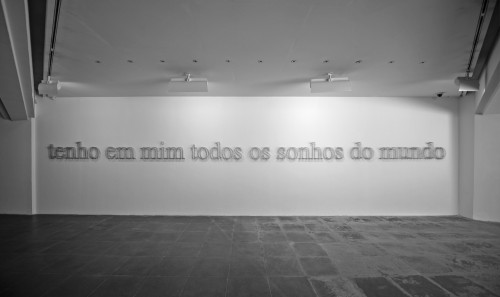

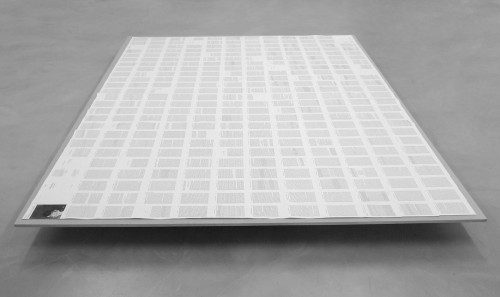

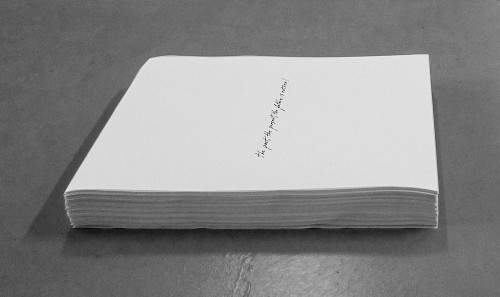

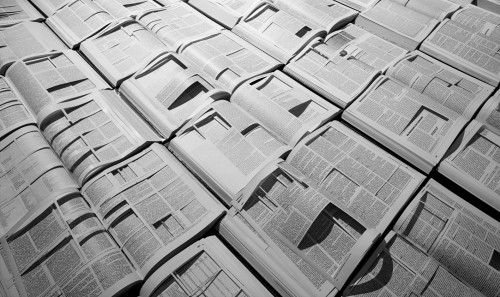

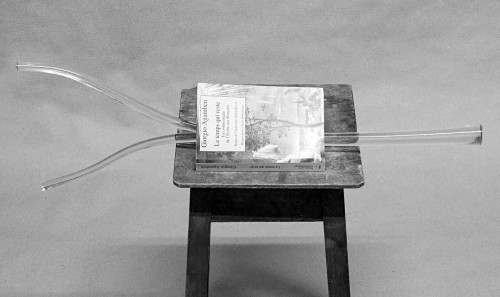

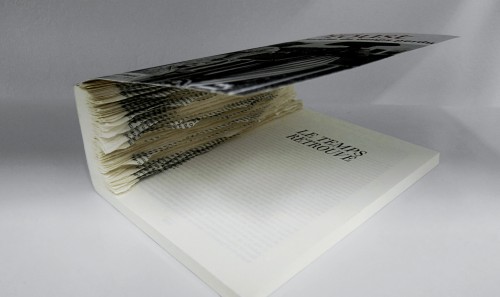

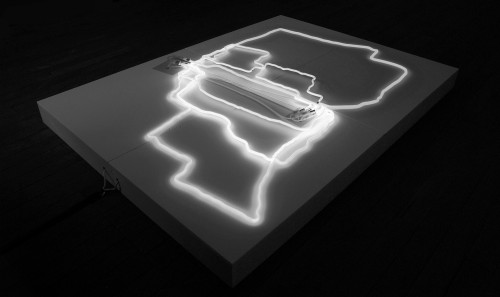

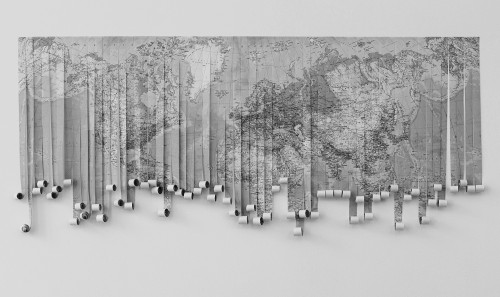

Floating pages, open to the air and light, I find them again in Venice. But there, laid out on a monumental ramp that measures nearly five meters at its highest point and slopes up from south to north in the shelter of a wooden-floored pavilion, they are white, empty, blinded by the real. By the thousands, the dried, wrinkled pages buckle and warp, paper yellow or white or pale grey, blank, lined or squared, covers blue, red, green, yellow, grey, black, pink, beige, brown, orange, permeated and hardened by salt. Notebooks run aground. They come from elsewhere, they have travelled, and we must lend eye and ear to what they carry within them. An invisible text. An unreadable text. Written by the sea.

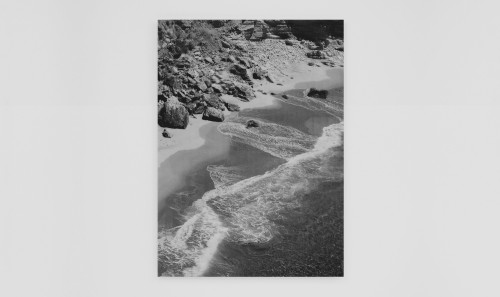

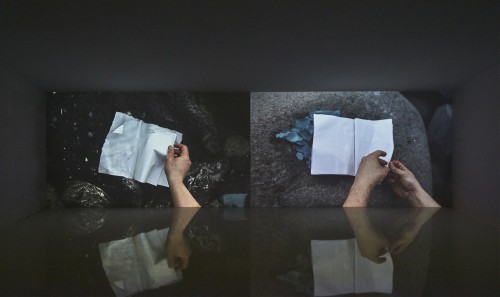

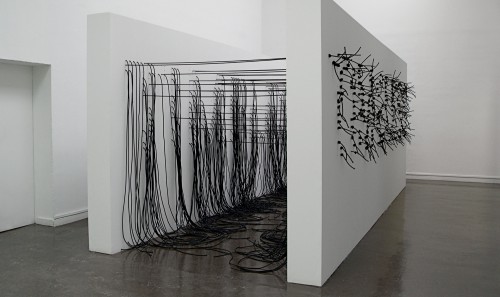

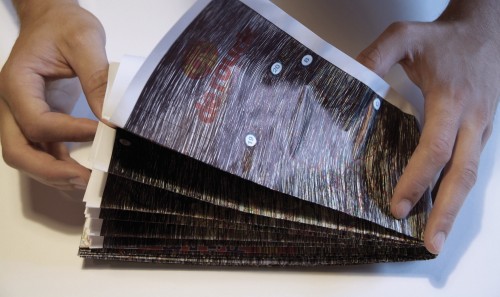

What would the sea say if it could write? This sea. Not just any one. This sea of origins, this sea of stories, this sea of journeys and wandering. This sea on which rises the rosy-fingered dawn. The floating pages on the Venetian slope recount the stories of those who have long swum in the deep waters of the margins of the wine-dark sea. The artist sets off to find them, collect them, welcome them in the notebooks whose pages he turns under water. His gesture is delicate and attentive, his gesture is one of writing. A writing without writing. He invites with his hand, he handles, literally, the intangible words, the undetectable words, the secret words. All those words that float on the surface of the water. All those words settle on the white paper in a multitude of secret stories that constitute the library of the sea. We see it, he shows us filmed images of these gestures of writing, bending, crouched at the water’s edge, hand turning all the pages of a notebook one by one, the sodden paper folding in the foam, the waves and the rolling surf. What the artist, the wet‑handed scribe, tells us is that we can read differently. Blindly. By listening to the song of the floating pages.

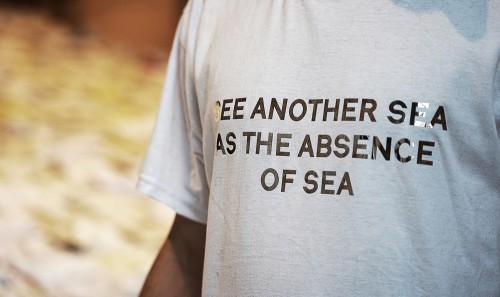

To build this library of the sea, the artist goes to the blue. An odyssey along shores to gather words made by waves. That’s the wandering life. Which is also the title of a travelogue by Guy de Maupassant, who, nearing the end of his life and weary of Paris, sailed to Italy, Sicily, Algeria and Tunisia. And the poet Yves Bonnefoy took the same title for his writings about an alchemist of colour, a painter who travels by boat from island to island in search of beauty. That painter may be Zeuxis, but the tale applies to any painter. Any artist.

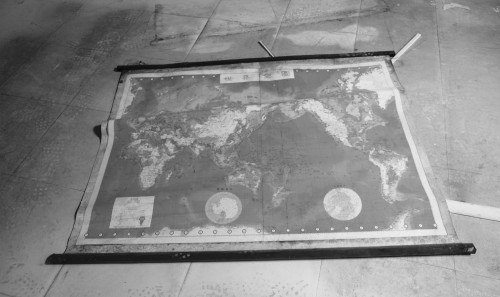

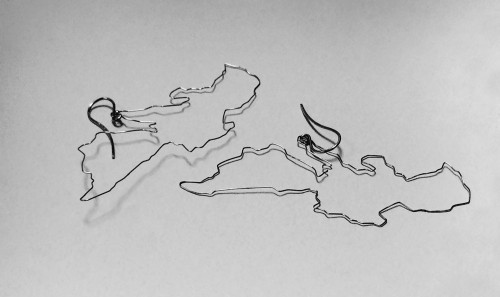

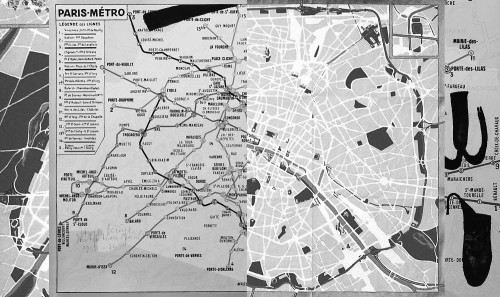

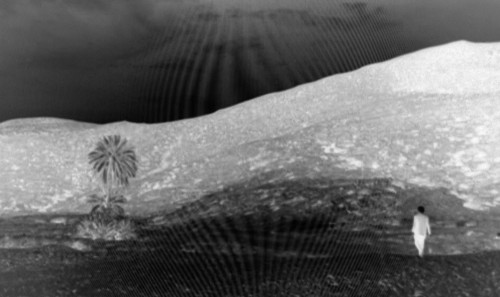

The artist laces his shoes and walks. Like a nomad, he roams the Mediterranean territory, walks along the hazy or barren sea. He began in 2013, around the Strait of Gibraltar. Malaga, Torremolinos, Marbella and on to Algeciras, Europa Point. At each stop, he acquired notebooks and immersed them in the foaming water, on the sand or rocks. On the African continent, he went to Ceuta. And in southern Italy, Sicily, Palermo, Catania, Syracuse, Acireale, Taormina, Porto Empedocle, Lampedusa, Linosa, and Naples, Pompeii, and the coast near Rome. Farther north, Trieste, then Umag, in Croatia. Lebanon, too, Beirut and the north coast. Barcelona and the Spanish coast. In France: Marseille, Toulon, Hyères, Antibes, Nice, then Monaco and Ventimiglia. On the Tunisian coast: Tunis, La Marsa, near Sidi Bou Said, Carthage, Djerba. And finally Jesolo, the Lido, Venice. We must listen to the song of the place names.

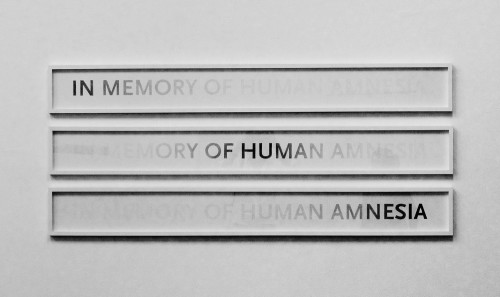

The artist goes toward the multiple thresholds these trajectories construct, to invent a moving space with indistinct borders. He lets himself be guided by the Homeric song of a contemporary Mediterranean, ages converging. These landscapes populate our memories and populate themselves with a new, unspoken and unwritten memory, that of the men and women and children who cross it. The sea is thus the receptacle of a myriad of stories that we must hear beyond the silence and the forgetting. The myths, Greece, the today of boats that save and wait offshore to be welcomed. It is about encounters and what the water brings of sharing from the shores on every side of this almost landlocked sea.

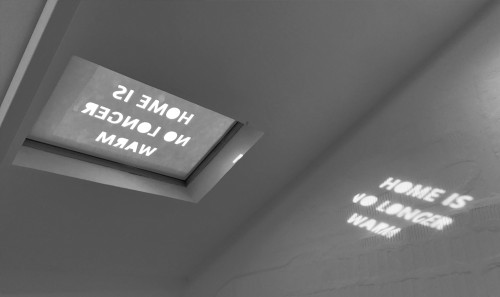

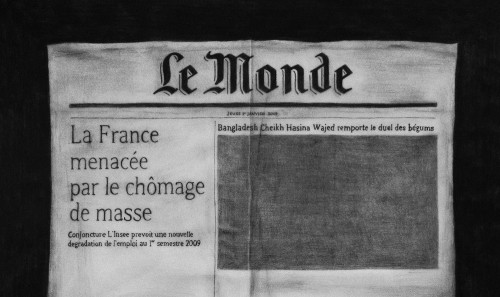

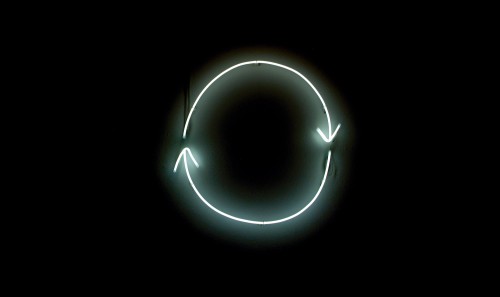

For the Mediterranean is a liquid route, a watery way. One February morning I heard on the radio the voice of the Italian writer Erri de Luca speaking in perfect French about Europe and the Mediterranean. Recalling Homer’s descriptions of the sea as “wine-dark,” “hazy” and “barren,” he said, it is a watery way (hygra keleutha). It is via this watery way that civilization came to us, on the northern coast of the Mediterranean. It is via this watery way that astronomy, philosophy, poetry, theatre, geometry and even numbers arrived. In this watery way, which is path, which is movement, we also hear the voice that calls, that retains. In the voice of Erri de Luca, the watery voie (way) becomes the homonym voix (voice). And the Mediterranean is like a song that is heard from every shore.

We must hear, says Jorge Luis Borges, the song of the sea that binds and sunders. It is the only way, he says, or rather has Ariosto muse, for a book to truly be. “It needs the rise and set of the sun / Centuries, arms,” and el mar que une y separa, “the binding and sundering sea.”

The multiple languages do not appear, and yet they are there, inscribed directly on the paper, captured in the deposited salt. The orality makes sense.

The artist seeks in this watery way the voice of ancestors mixed with that of his contemporaries. He has heard that “myth is … a language which does not want to die,” that it feeds on meanings and turns them into “speaking corpses.” He has heard that “myth is a type of speech.” He listens, he gathers, he receives.

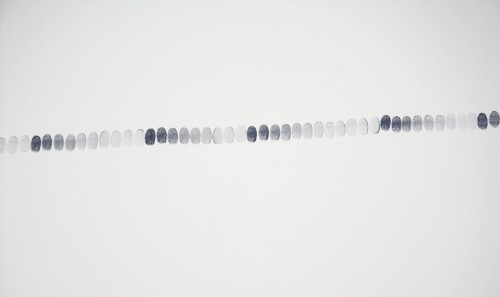

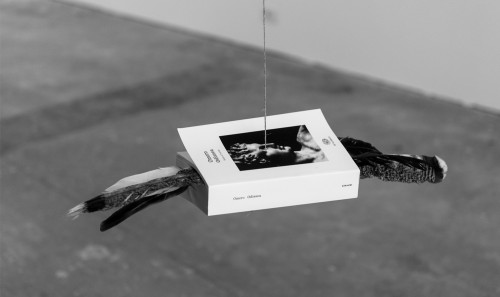

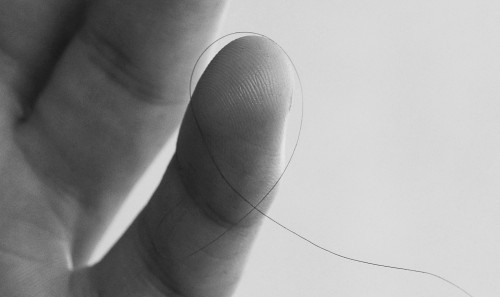

The artist does not write something, he writes. He writes without writing. He wants to set nothing in stone. He favours the flowing, the moving, the impermanent. His writing gesture renders an invisible, that of the throng of ghosts that haunt these waves. His gesture accompanies the words, his hand participates in the language. He may have read the ethnologist André Leroi-Gourhan, and perhaps the theologian and mystic Gregory of Nyssa, born in Neocaesarea in the 4th century, who believed that nature added hands to our bodies primarily for the sake of language, of communication. Turning the pages is an intention-to-say. An intention-to-write. And the artist lends his body to the voices. He affects himself.

In ancient Greek, there exists a grammatical voice between the passive and the active called “middle voice.” These three voices refer to the different positions of the subject in the process of an action. The active voice represents the subject as performing the action; the passive voice, as receiving the action. The middle voice indicates that the subject is involved in the action in some particular way. Situated between energeia and pathos, it serves to denote actions one performs and at the same time receives; for example, touch and be touched.

When Roland Barthes addresses writing in an absolute sense in his lectures on the preparation of the novel, or in the essay “To Write: An Intransitive Verb?,” he associates the intransitivity, the absolute nature, of the verb “to write” with the middle voice of Greek grammar. He sees the middle voice as characteristic of modern writing, a writing where the writer affects the language as much as she affects herself through contact with it. For this voice points toward experience and at the same time turns back toward passivity. Various actions can be expressed this way in Greek by using the middle voice: to be born, to die, to follow or embrace a movement, to enjoy. An example frequently given is that of the verb “to untie” (one’s laces). I untie for myself (my laces). This action affects me.

Writing is a means. A very powerful means, according to Barthes, where the subject affects itself in the writing. And in the artist’s singular gesture of writing, this affecting of self occurs. He does not write to or on or something. He writes. By means of the sea. And this gesture touches him as it touches the water and the floating stories, as it touches the transparent ghosts. The artist experiences the limit situation of being at once the producer and the product of a single gesture that he transports and transposes on his journey. He invents a signless writing made by salt and water, by sun and wind, by memories and his hands.

The artist observes the permanent wavelike movement of a liquid world, which enacts the modernity described by the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman. He finds his way. He makes a map of writings to guide us. He does not reject the permanent movement, he embraces it, makes no attempt to resist it. He follows an itinerary sung to the rhythm of walking. He, too, has no need to see. He frees the phantom word.

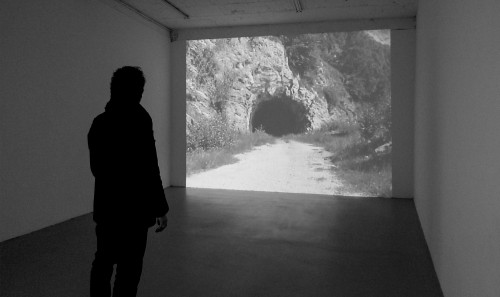

Homer was blind, it is said. Borges became blind. In his introduction to the Odyssey, the writer Michel Butor speaks of blindness and the remarkably visual nature of the poem. He writes, “I personally met in Egypt, a country where flies swarm in children’s eyes, Coptic cantors [who are] always blind, an old man transmitting his art to a young assistant. Song was, in this way, the refuge of the blind.”

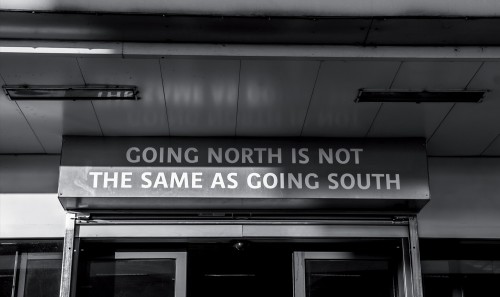

The artist roams the space from north to south, hurries in the hours of the dawn and the night, and collects the wandering songs become refuge. The refuge of the blind that is the library.

Sally Bonn’s research interest lies in writing practices in the field of visual arts. She is the author of numerous essays and a critical fiction. Also an art critic and occasional exhibition curator, she teaches aesthetics at Université de Picardie Jules Verne, in Amiens.

- Stated by Sayat Nova in Sergei Parajanov’s film The Color of Pomegranates (Sayat Nova, 1969). After decades of being confined to the festival circuit, the original Armenian version with English subtitles was digitally restored and re‑edited in 2014 and released on DVD and Blu-ray in 2018.

- Jorge Luis Borges, “Ariosto and the Arabs,” in Dreamtigers, trans. Harold Morland (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985), 82.

- Roland Barthes, “Myth Today,” in Mythologies [1957], trans. Annette Lavers (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1972), 132.

- Ibid., 107.

- Roland Barthes, The Preparation of the Novel [1978-80], trans. Kate Briggs (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

- Roland Barthes, “To Write: An Intransitive Verb?” [1966], in The Structuralist Controversy, Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato, eds. (Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1972), 141-142.

- In the words of Michel Guérin, we treat the gesture “comme le moyen d’exprimer, faute de mieux, le vœu d’une parole fantôme” [as the means to express, for want of better, the wish for a phantom word], Philosophie du geste (Arles: Actes Sud, 1995), 14.

- Michel Butor, “On dit qu’Homère était aveugle,” introduction to Œuvres d’Homère II – L’Odyssée, translated from the Greek by Frédéric Mugler, (Paris: La Différence, 1991), 12.