Sharing Intensities

Paul di Felice

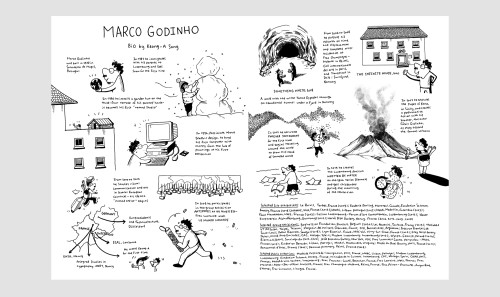

Since our first real meeting, at the exhibition Shared Differences, part of the 2007 Luxembourg, European Capital of Culture program, our paths as artist and curator have often crossed. We connected immediately, forging an artistic and human bond that still holds fast. With him, it’s hard to separate artistic moments from ordinary existence. In his mind, the gap between life and art is infra-thin, barely perceptible. And so, time spent in conversation and creative letting-go, between bucolic breaks and in situ work, between unstructured conceptualization and controlled improvisation, is integral to the creative process that Marco Godinho is by nature inclined to share.

Autre chose

I had read the great Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa in the Italian version by the contemporary writer Antonio Tabucchi, translator and champion of Pessoa’s work, and Marco’s love of literature led me to re-immerse myself in that marvelous literary universe. Shaped then as now by simple gestuality and profound minimalism, his installations remind me of Pessoa’s definition of beauty: “Beauty is the name of something that doesn’t exist / But that I give to things in exchange for the pleasure they give me.”

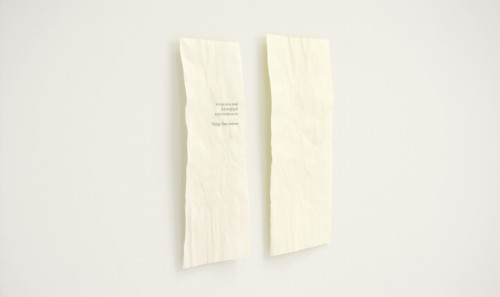

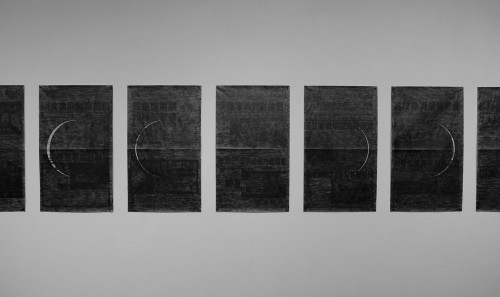

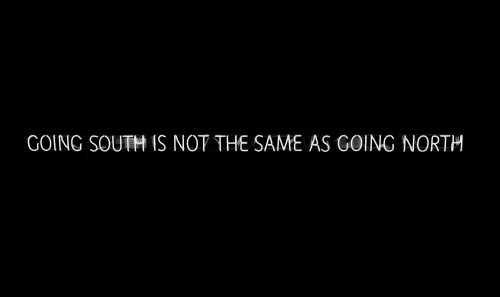

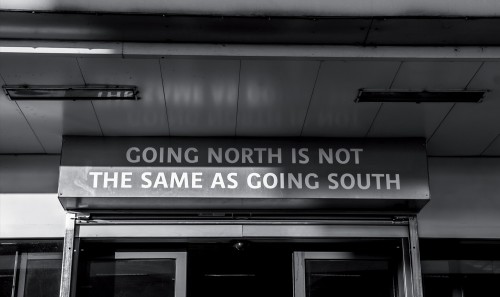

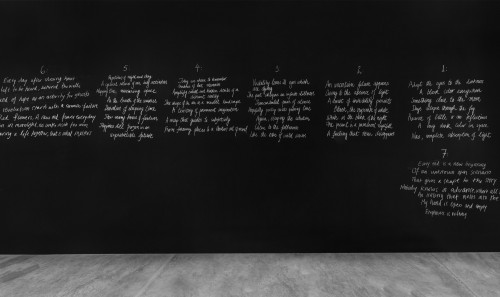

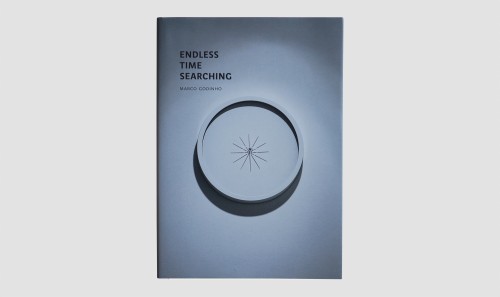

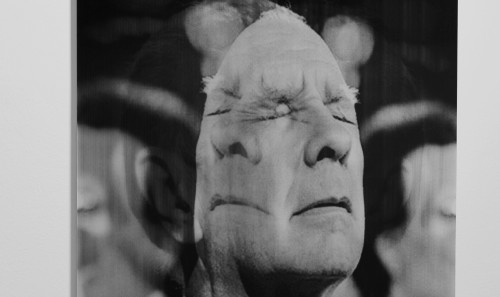

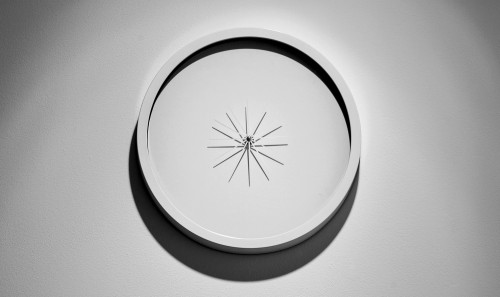

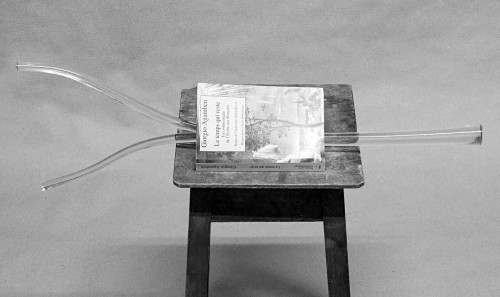

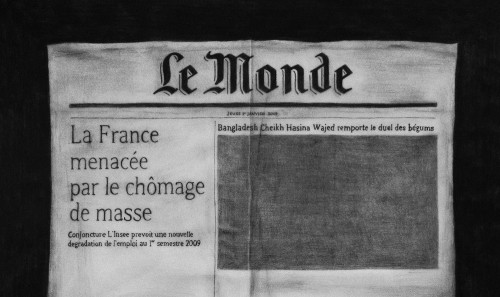

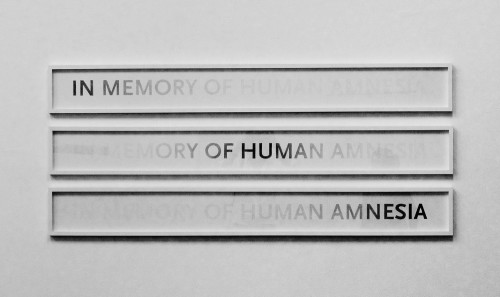

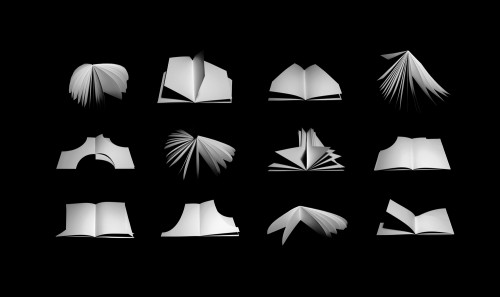

Marco Godinho would speak of intensity rather than beauty, because for him the notion relates more to action and attitude on a flexible scale and less to an exclusive canon, as the classical concept would have it. Likewise, whereas Pessoa’s standpoint is akin to introspection, Marco’s approach takes on relational dimensions. Even as he addresses social issues, he shares a contagious wonderment before the little things of life that nourish his sensitivity and creativity. But his work is driven as well by a sometimes diabolical pursuit of detail and the necessary pleasure of deconstructing the real and its representations. Poetry, language play and philosophy inform his artistic conceptions but also serve as subjects, or as tools and supports for his visual reflections. As a result, his seemingly light works respond in artistic form to philosophical concepts, as in Autre chose, where the Derrida sequence seems to illustrate the thinker’s theory of hauntology and, in a certain way, the deconstruction of stereotypes.

Forever Immigrant

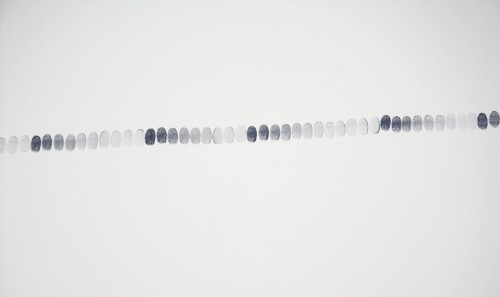

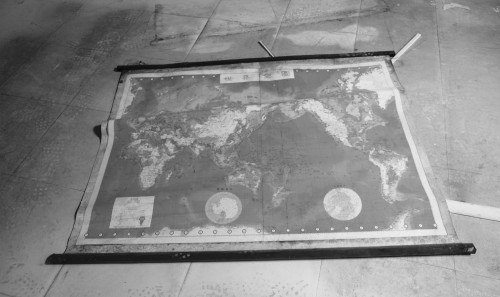

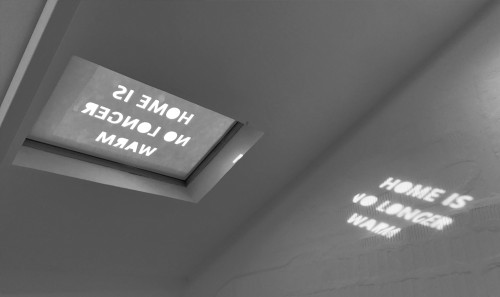

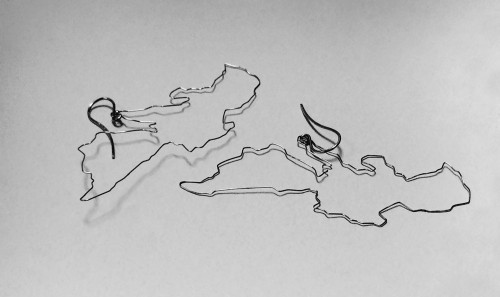

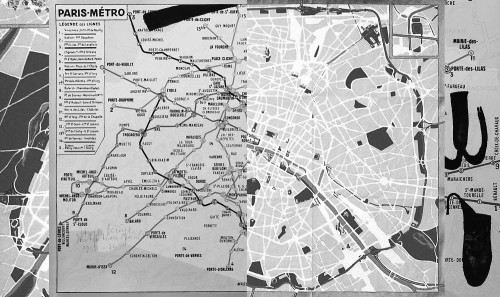

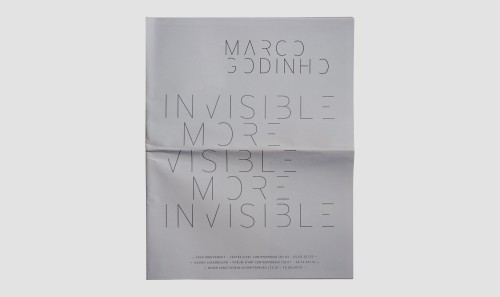

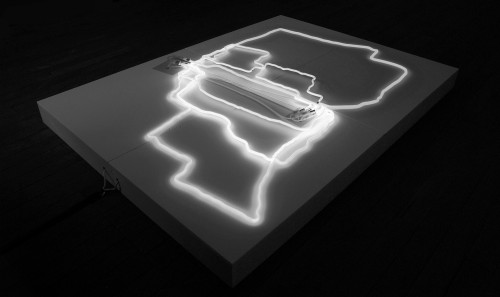

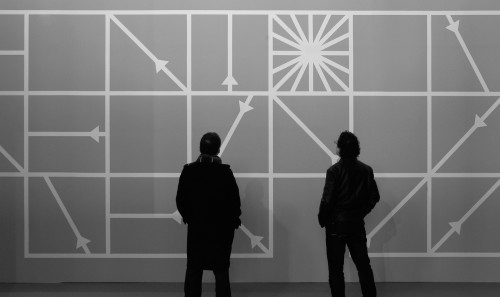

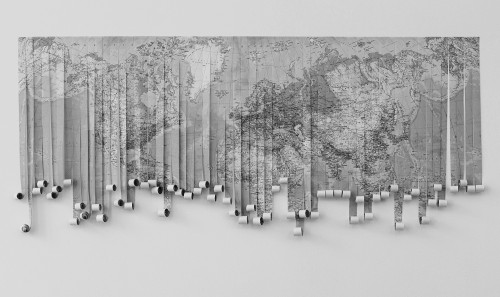

Marco’s themes, or rather preoccupations, vary but often revolve around “the other,” in the sense of limits, borders and representations. In 2007, the “Migration” theme for Luxembourg’s Year of Culture gave him the opportunity to explore these questions of lifelong interest. In that case, he irrefutably deconstructed the notions of representation in the Schengen Agreement and Convention region by reinterpreting its cartography through a gesture of erasure and revelation. Several works in the exhibition, such as Welcome Stranger, written in white neon, and Mental Type, an alphabet of the artist’s invention, refer to the theme of “the other” and “us” in the face of personal isolation.

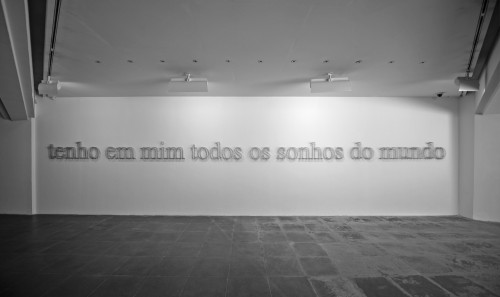

Does confinement in our inner worlds, of which Fernando Pessoa spoke, prevent us from seeing real life or simply from living it as if in a strange or dreamlike world? With his installation of Pessoa’s phrase “Tenho em mim todos os sonhos do mundo” (I have in me all the dreams of the world), spelled out with large steel nails in reference to the workers and former factory where the piece was first shown, in 2007, Marco metaphorically evokes the dichotomies between reality and dream, between materiality and illusion. Might the interstices he speaks of through his artistic utopias be a way of filling the gap, of confronting the absence and conceptualizing the invisible? This gap, which according to Ernst Bloch is the very definition of utopia, plays a central role in Marco Godinho’s artistic process. Art being not an escape route from life but an attitude, an approach inscribed in everyday life.

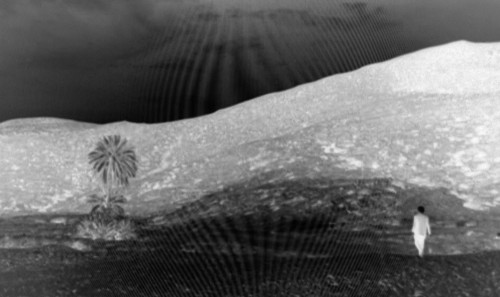

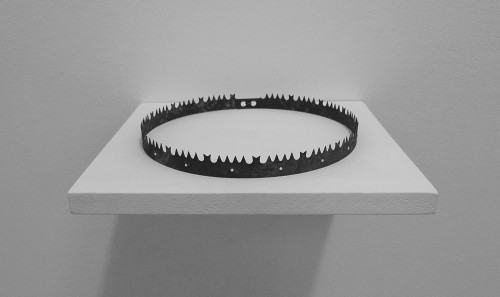

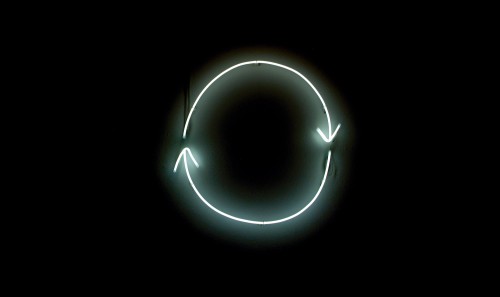

And if our life were nothing but a long journey? A sort of peregrination “in endless search of an elsewhere, a place to briefly stop before setting out again,” as Marco likes to say. Inspired first by his immigrant family experience and then, of necessity, by his more universal thinking on present-day migration issues, works like Forever Immigrant are perpetually fuelled by the uncertainties of nomads and foreigners. “This form of feeling like a foreigner everywhere is a feeling I like to keep alive at all times.” More than providing answers, these works extend the questioning while, at the same time, drawing on the wandering. Begun like an uncharted voyage a dozen years ago, his journey has taken him, like a modern Ulysses, from Portugal to Spain and North Africa, from France to Italy and Greece, and, finally, marking an important milestone, to Venice.

Ai Murazzi, Lido, Venice

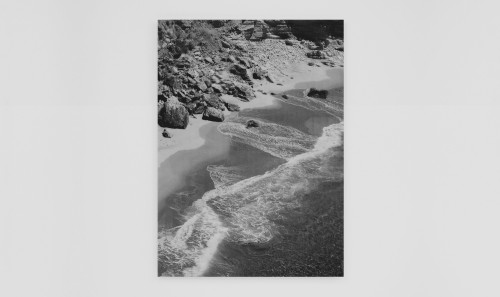

About five kilometers (as the crow flies) from the Arsenale, the Murazzi, dikes of white Istrian stone built in the late 18th century, hold back the waves of the Adriatic and, with them, all the secrets of the cast-off objects that wash up there. Contemplating the silvery glints of the breakwater lit by the setting sun, far from the tourists of Venice, we resume the habitual discussion of our views on art in the context of the Biennale. We talk about the difficulty of responding artistically to the particularly “Venetian” contrasts as a participant in the world’s leading contemporary art event.

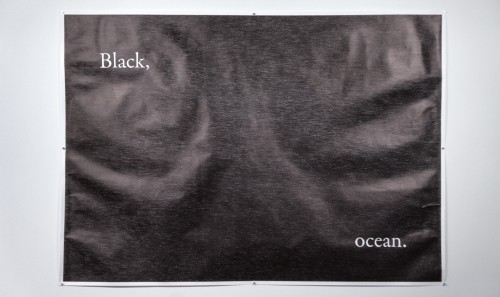

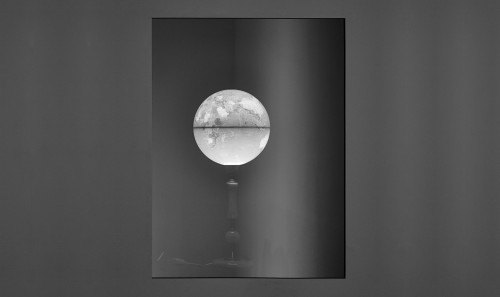

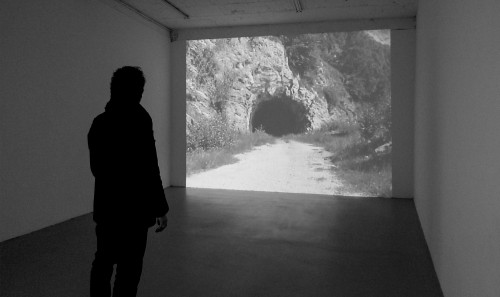

This calm contemplation of the sea, with its evocation of mirror and infinity, takes us to a part of his oeuvre inspired by the Mediterranean, its ancient myths and its contemporary realities. “That sea forever starting and restarting,” as Paul Valéry wrote in the poem “The Graveyard by the Sea,” is at the heart of his maritime metaphors. Always the Mediterranean, its shimmer, its migrations and its conflicts, which Marco Godinho seems to exorcise through his artistic actions. In the video Cabo da Roca (2007), titled after the westernmost point of mainland Europe, in Portugal, the artist is powerless before the infinity of the ocean. His action is tense. Walking becomes exploratory, the body is reminded of its limits and the sense of void outweighs the intoxication of scenic beauty.

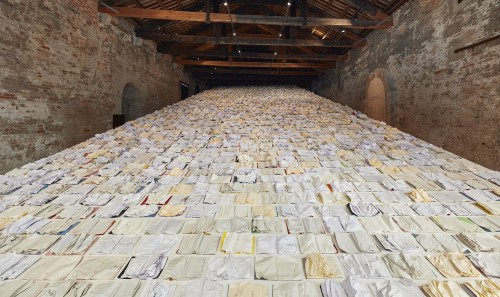

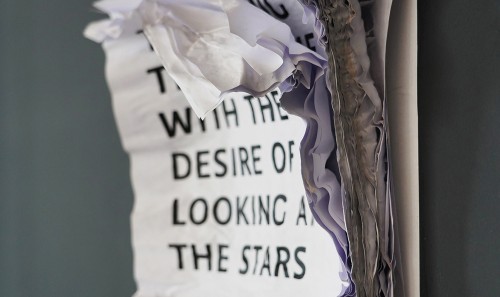

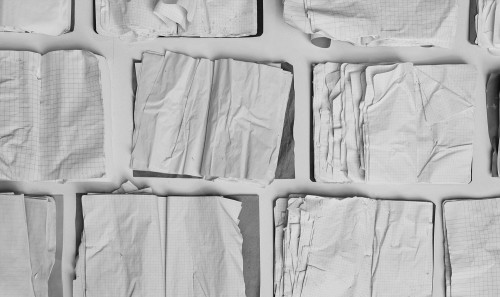

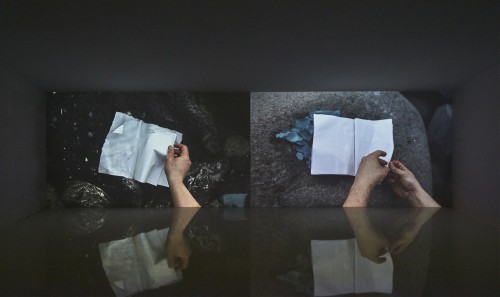

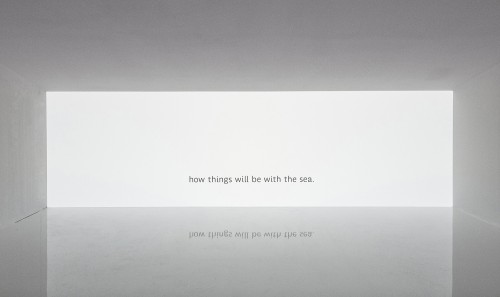

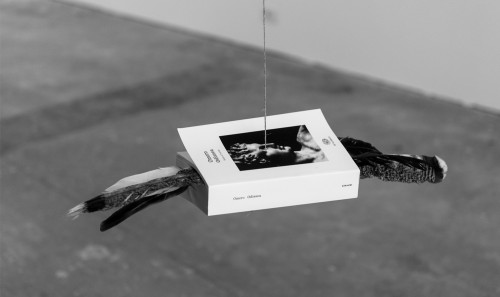

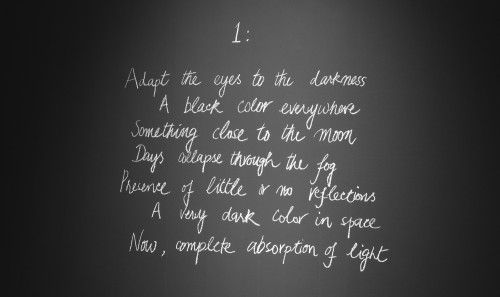

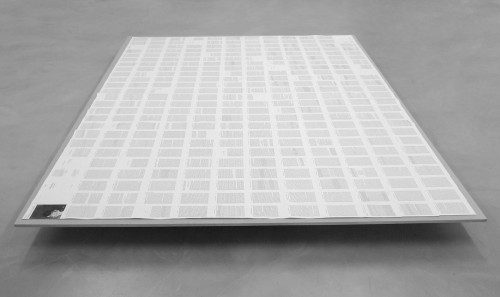

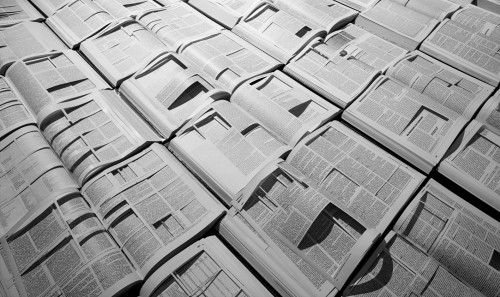

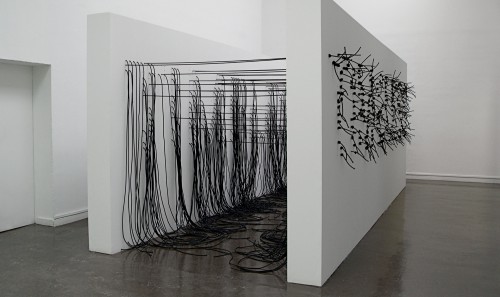

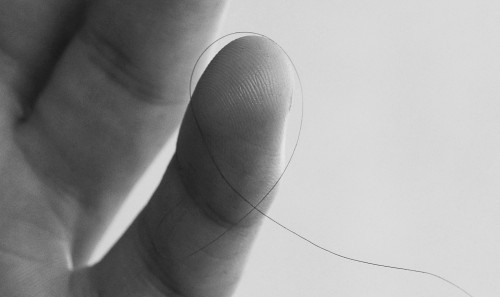

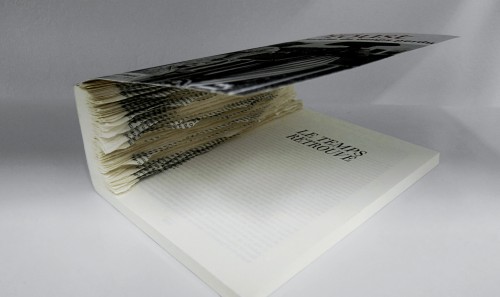

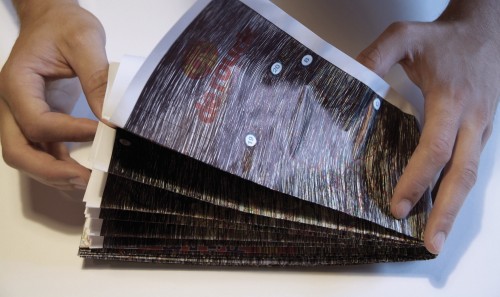

While threshold, resistance and mutation are addressed in Marco’s work, it is definitely the notion of nomadism that most informs his practice. Written by Water, a work begun in 2013, confronts the viewer with an ephemeral presence through the ritualized gestures of immersing notebooks in water (video), but also through the installation of notebooks bearing material traces written by the waters of the seas of Gibraltar, Ceuta, Palermo, Lampedusa, Djerba, Carthage and Trieste. In 2019, the artist borrowed the title Written by Water for a large-scale installation created for the Luxembourg Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The installation is composed of some three thousand notebooks marked by the material traces of the water’s writing. Visitors are invited to literally immerse themselves in the video installations that, in their way, recount the artist’s journey. Between the solemn gestures of submerging notebooks, the recorded stories of visually impaired exiles who speak of their relationship to the sea, and the narratives scripted according to each location, Marco Godinho’s work, at once poetic and political, opens new fields of interpreting questions of mutation and migration. Here, as elsewhere, the artist speaks of the unstable beauty of our changing, uncertain world that emanates from the continual vagaries and vicissitudes he seeks through his art.

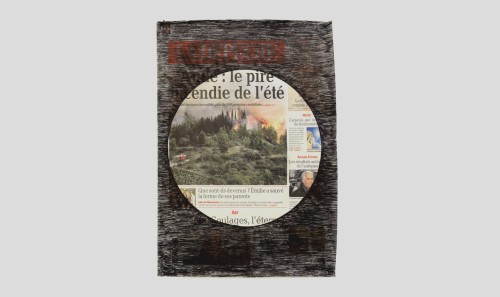

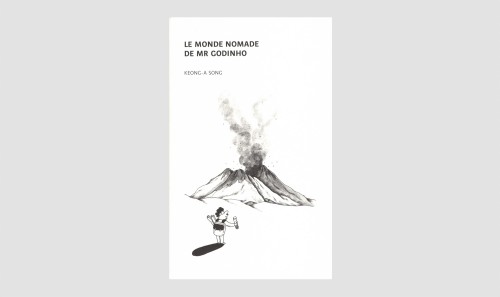

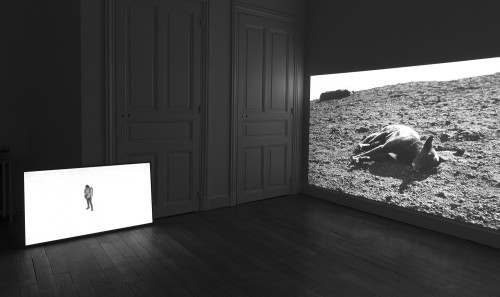

This is expressed even more in recent works that interweave documentary and fiction, such as Notes sur cette terre qui respire le feu (2017), where Marco invites visitors to engage with his experience on the Etna volcano, in Sicily. In this case, he asked his brother Fábio, an actor, to make the climb with him, favouring, as in other projects, forms of collaboration where sharing and relating are important. “I can change by exchanging with the Other and still not lose or distort myself,” he likes to say, quoting the great Martinican poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant.

It is true that for Marco an artistic project is not really a solitary act; instead, it is part of exchanging on all levels and building on a coherent body of work sustained by his journeys and physical and literary encounters. Hence the need for a stop in Trieste, to pay homage to Joyce and his Ulysses by multiplying points of view, like the author, and borrowing a disconcerting narrative of flights of fancy and reminiscences.

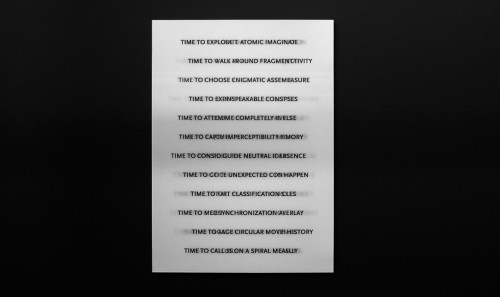

Whether a poetic or material re-enunciation of limits and geographic borders, as in Cabo de Roca, or a multifaceted recording of wanderings, traces of physical and metaphysical passages, as in Written by Water, Marco Godinho’s works, despite their apparent fragmentation and haiku rhythm, their poetic and poïetic power, form a whole that seems driven, as he says, “by an eternal beginning, a detonator of possibilities, of opening to the world.”

Paul di Felice holds a Ph.D. in Visual Arts. He has taught modern and contemporary art history and art education at University of Luxembourg, in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. An art critic and curator of international contemporary photography exhibitions, he is also co-editor and co-publisher of Café Crème edition & mediation, a member of the editorial board of the online magazine lacritique.org and coordinator for Luxembourg of the European Month of Photography (EMOP).

- A Little Larger Than the Entire Universe: Selected Poems by Fernando Pessoa, ed. and trans. Richard Zenith (London: Penguin Books, 2006), 29.

- Fernando Pessoa, “Tabacaria,” in Selected Poems, trans. Jonathan Griffin (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1974), 111.

- Marco Godinho, interview by Christophe Gallois, in Mondes nomades (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2017).

- Édouard Glissant, “Drawing Lines in the Sand,” Le Monde diplomatique, November 2006.

- Marco Godinho, interview by Christophe Gallois, in Mondes nomades (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2017).