Oblivion (Water)

Oblivion (Water), 2019

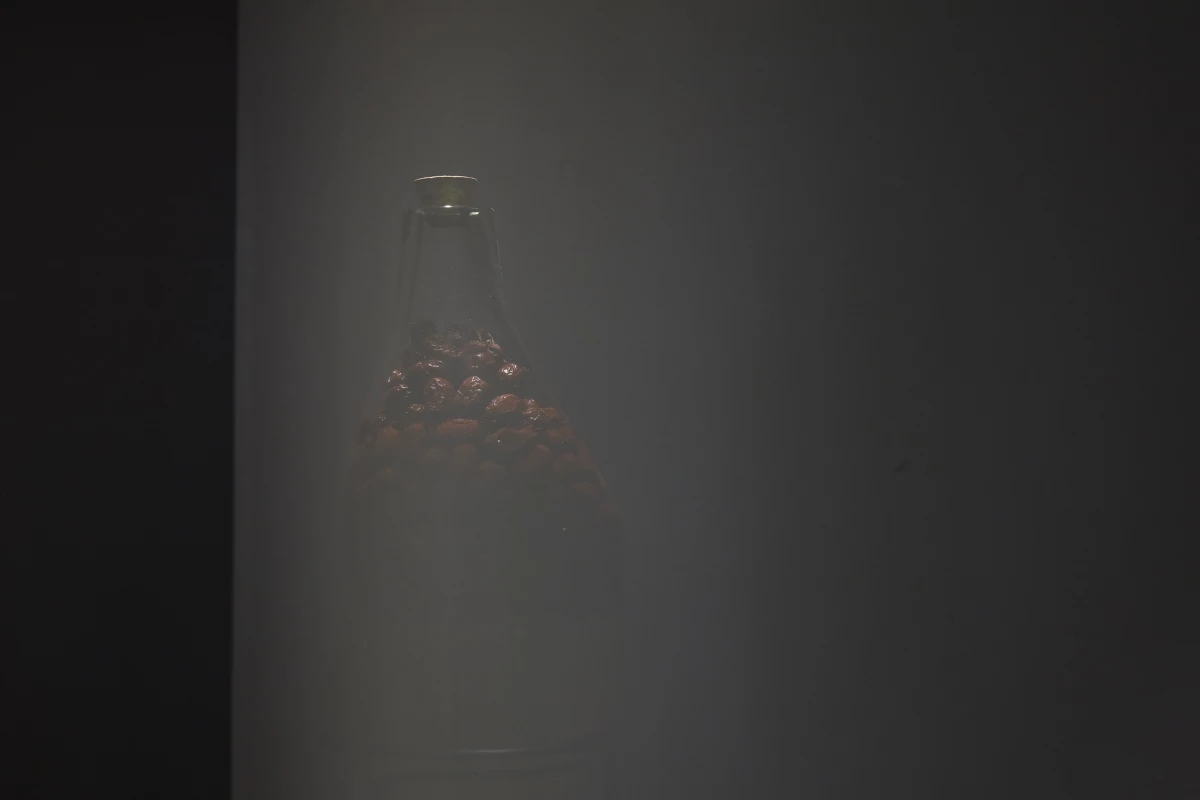

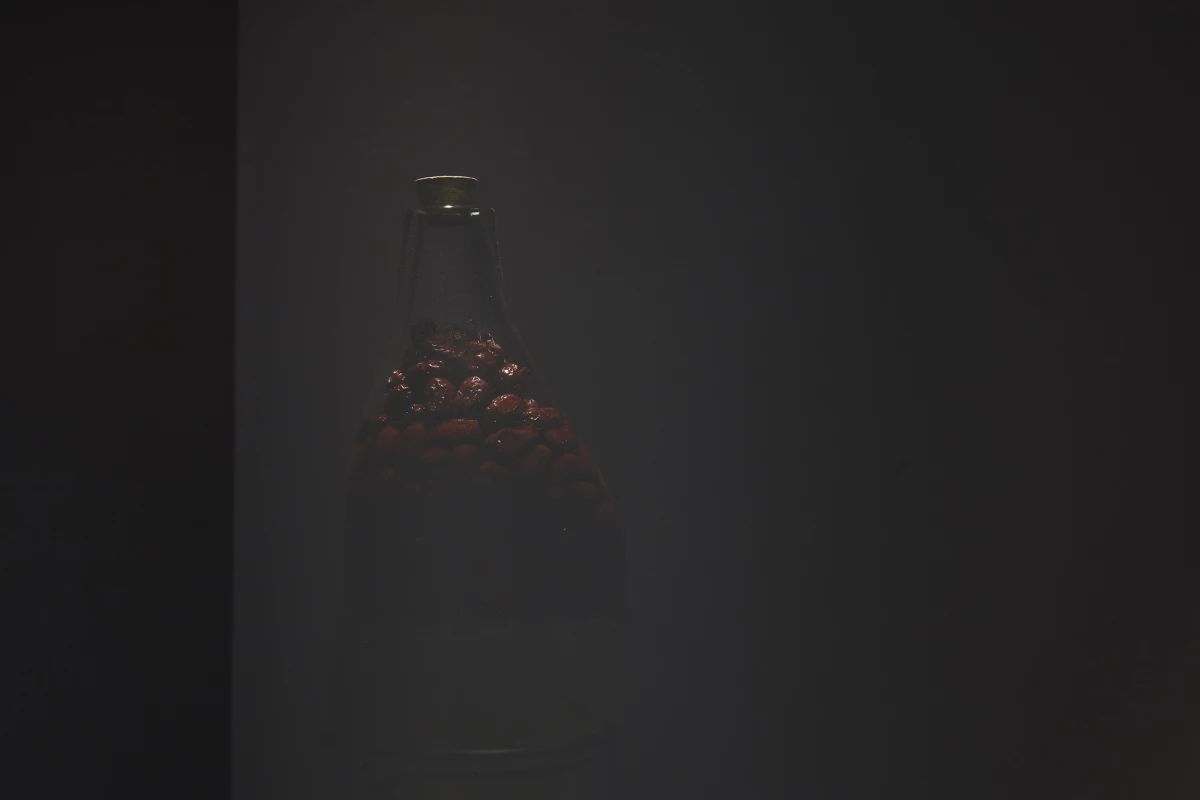

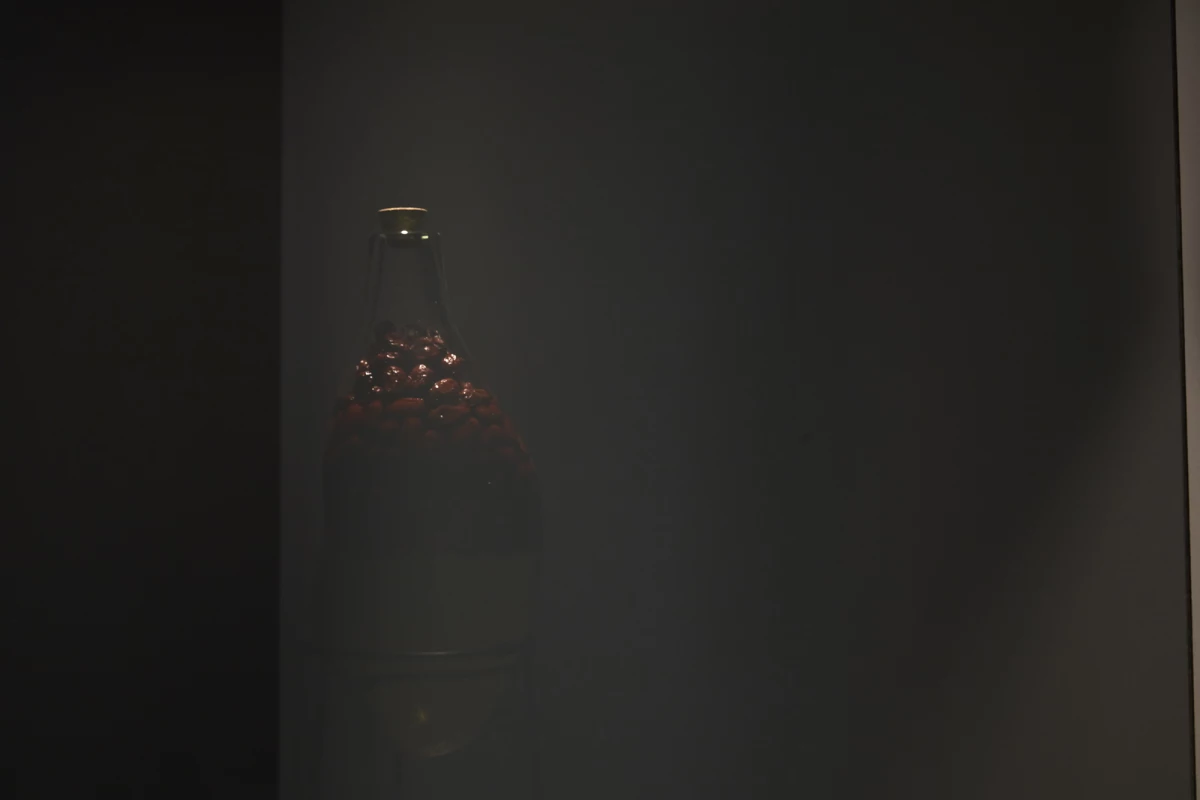

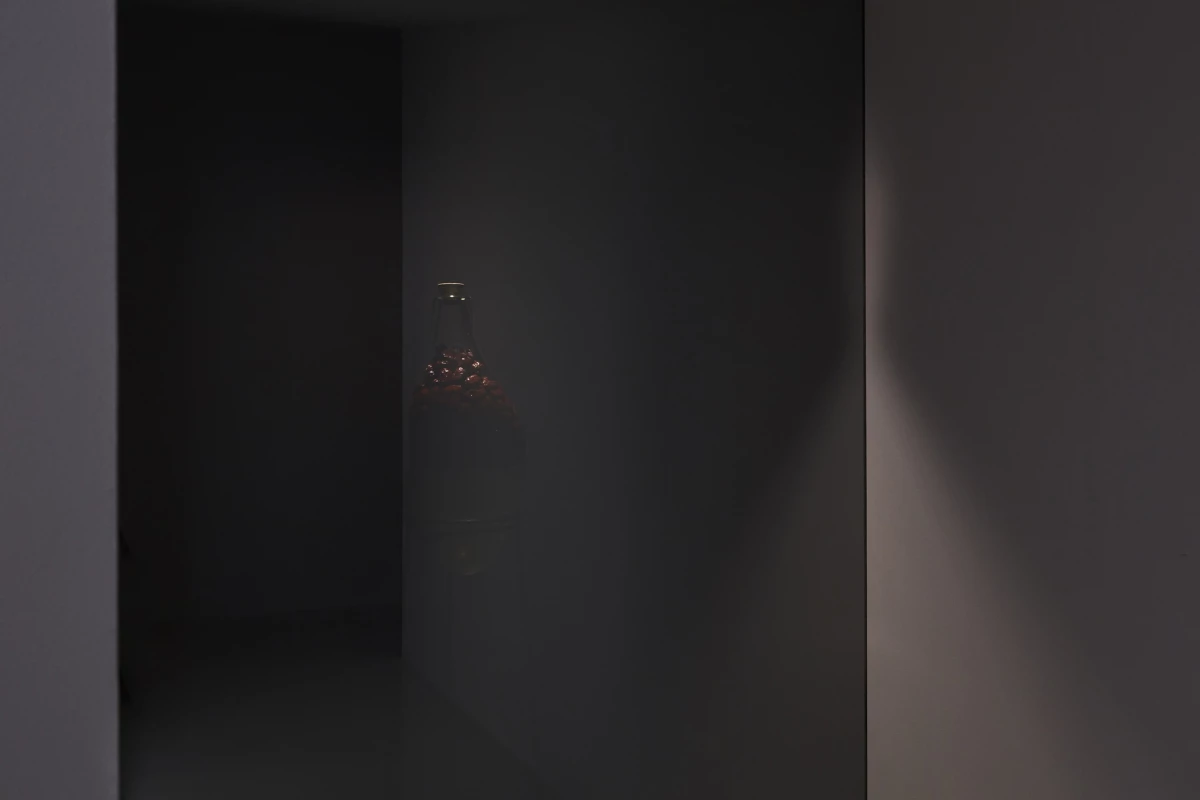

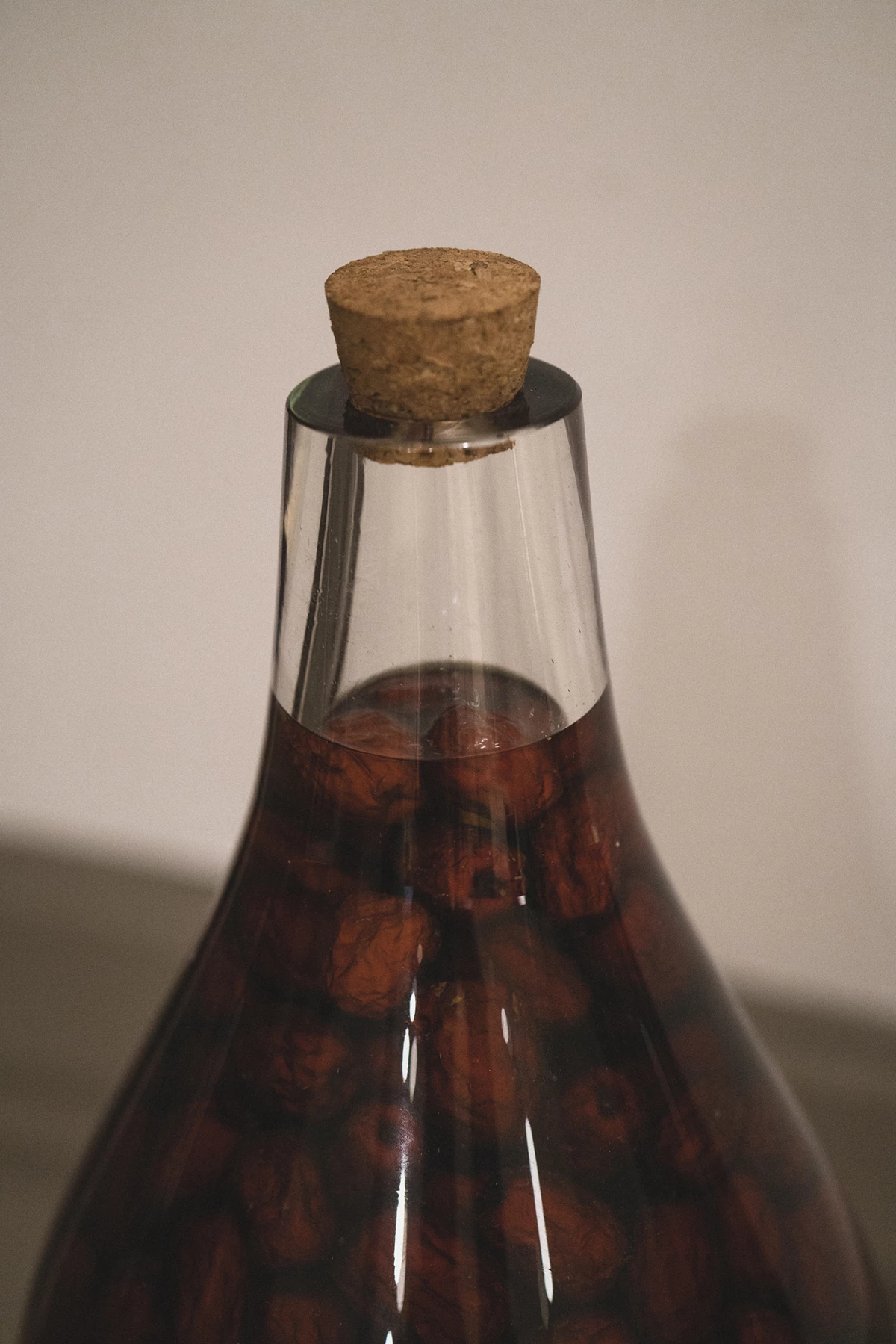

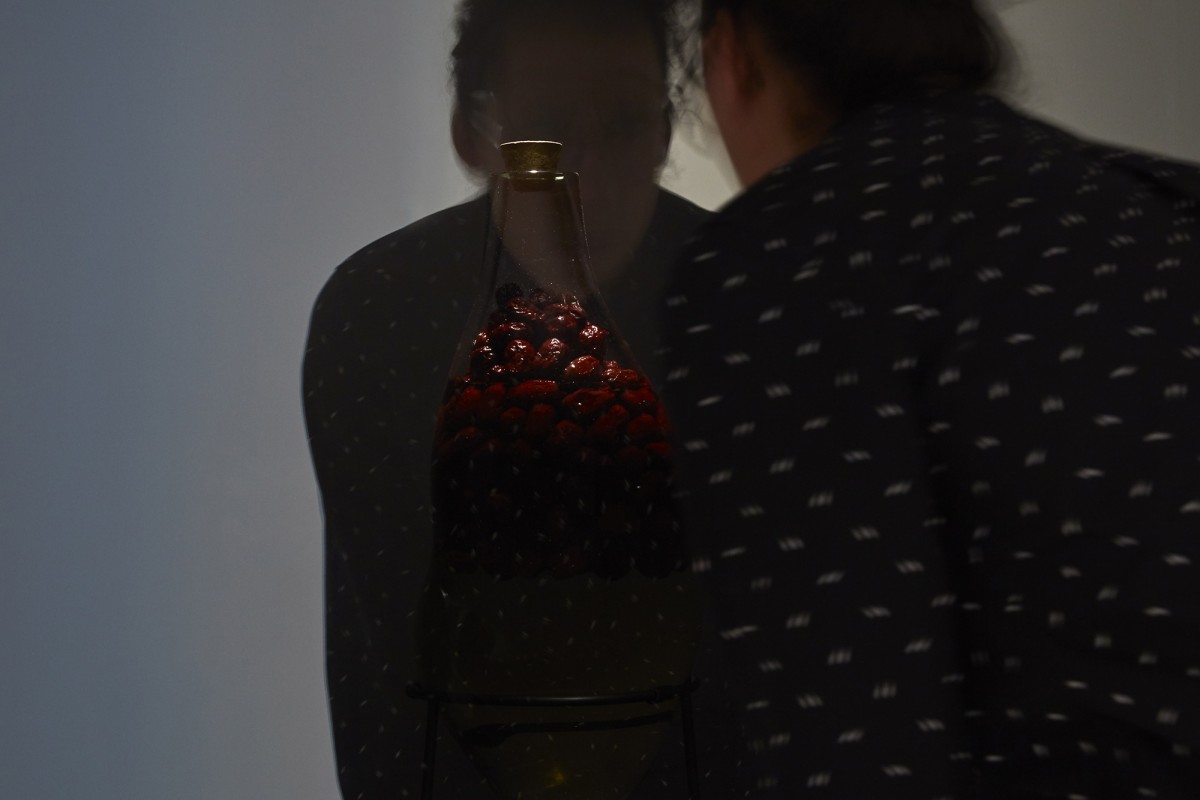

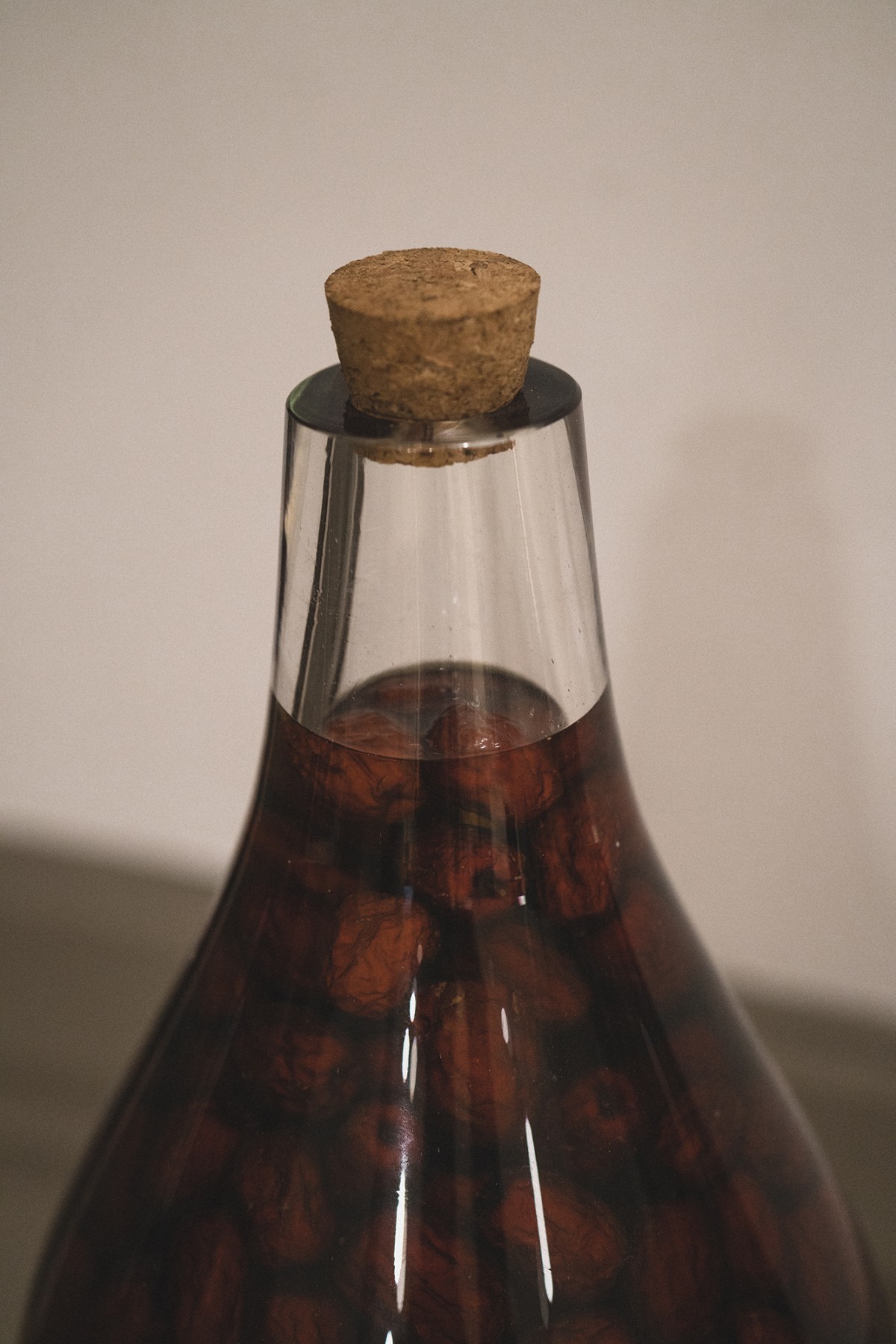

Opening ceremony, aqua vitae from Portugal and Luxembourg, jujube fruit from Korea, blown glass bottles, cork, metal, one- way mirror, light system, time-based work, performance

–

Oblivion (Water), 2019

Ending ceremony (tasting event on the last day of the Biennale), performance

–

Oblivion (Water), 2019

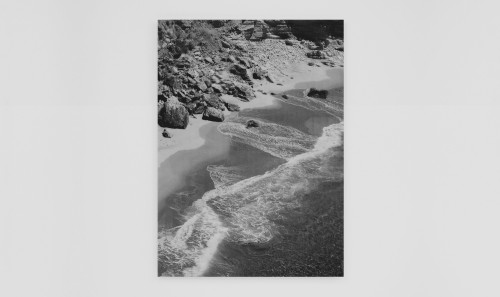

Colour photographs

Dimensions variable

Oblivion (Water) is a work that evolves through out the Biennial, which lasts approximately seven months. This is the ideal length of time to macerate Korean jujube fruit in Luxembourgish and Portuguese brandy, which is thus turned into a placebo. Between the opening ritual (first day of maceration) and the ending ceremony (tasting event on the last day of the Biennale), the exhibition space becomes the site of a process during which the work is developed and transformed.

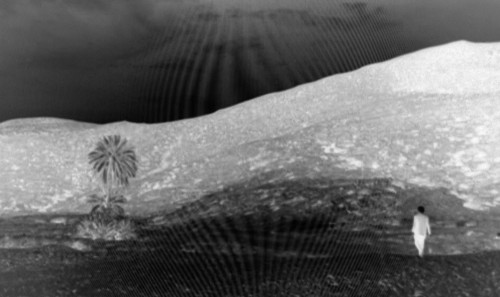

In Homer’s Odyssey, Ulysses arrives on the island of the lotophagi, or lotus-eaters (now Djerba in Tunisia), who feed on the lotus flower, “the fruit that brings oblivion to those who eat it.” It stands for a particular threat to all explorers: that of “so kind a welcome,” so hospitable a land that one no longer wants to return home. As soon as the sailors eat the fruit, their desire to return home vanishes.

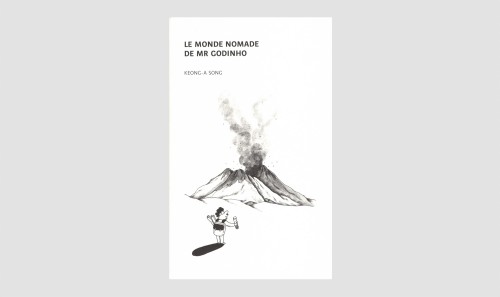

According to researchers, the fruit of oblivion might well be the jujube (probably native to Asia, it appeared in Africa more than 4,000 years ago). In search of the wondrous fruit, Godinho first travelled to Djerba, but when he failed to find any jujube (it was not the right season), he decided to try his luck in Korea, an important jujube producer as well as the country of origin of his partner. In Oblivion (Water), Godinho begins by deconstructing his own (Portuguese-Luxembourgish) identity and offers all those who taste the liquid to open up more to the other and forget the sectarianisms of identity and nationalism – open up to what is foreign, open up to the world and “claim the right to opacity,” as Édouard Glissant put it, for whom “the only way to fight glo balization [is] not by withdrawing into oneself, into one’s own condition, but by establishing relations with the other. And this is a real dimension of Utopia.”

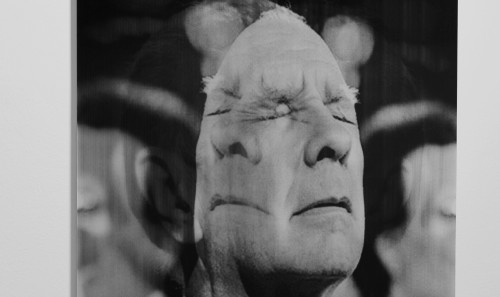

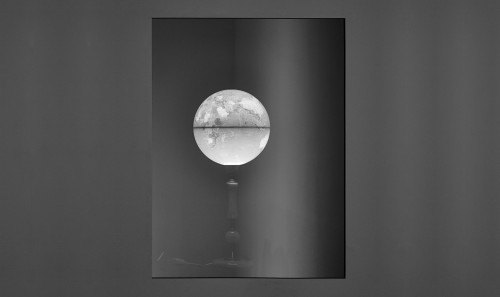

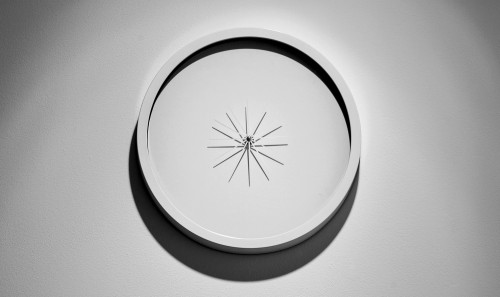

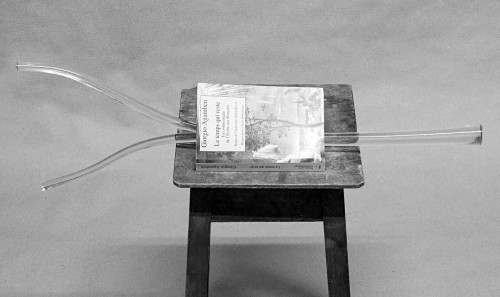

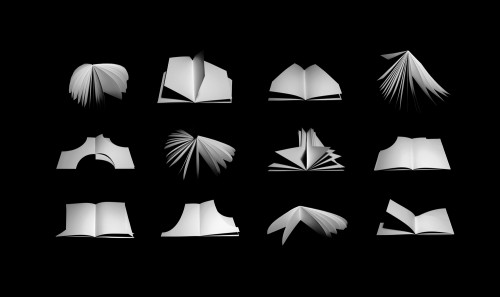

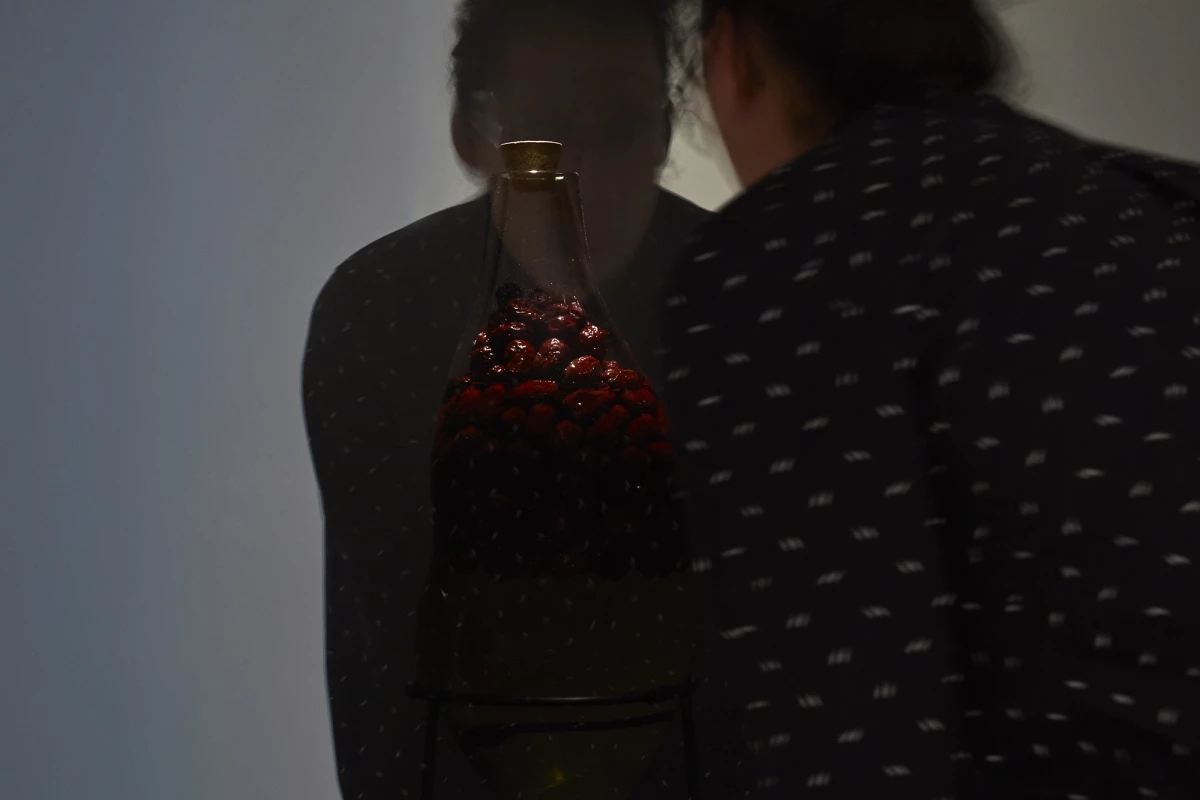

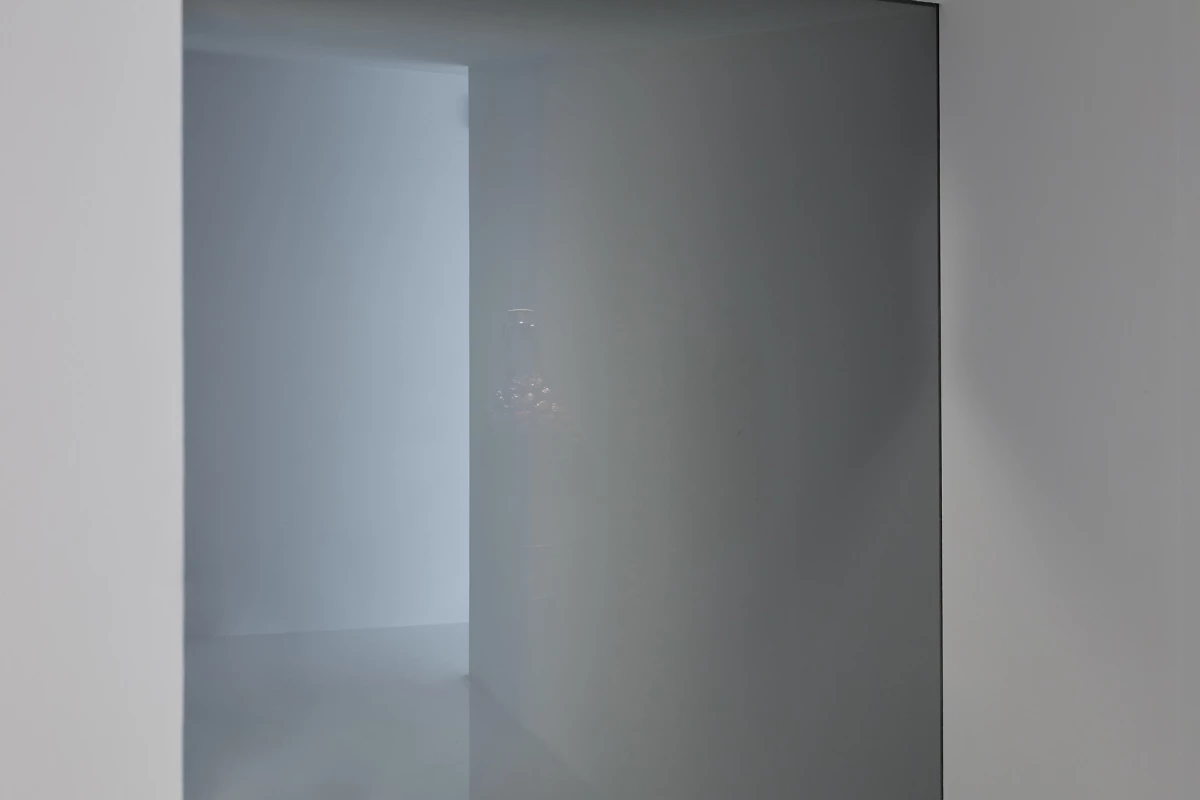

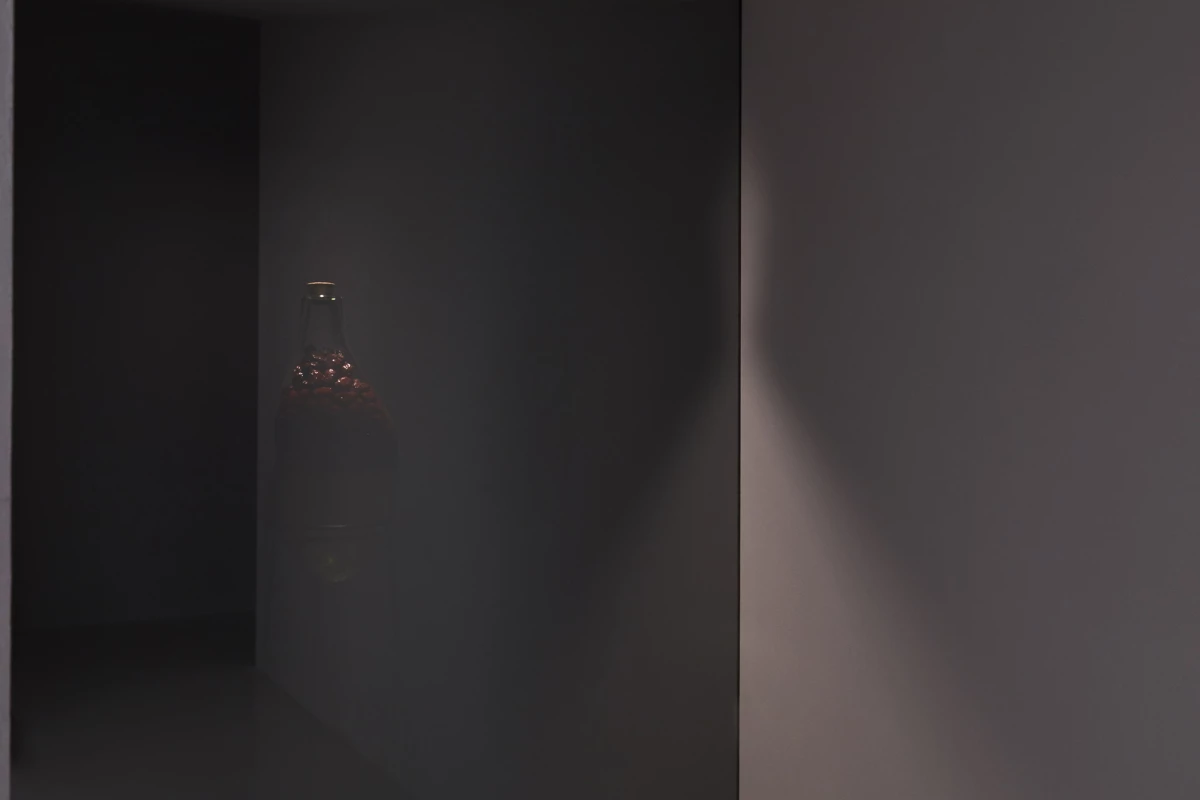

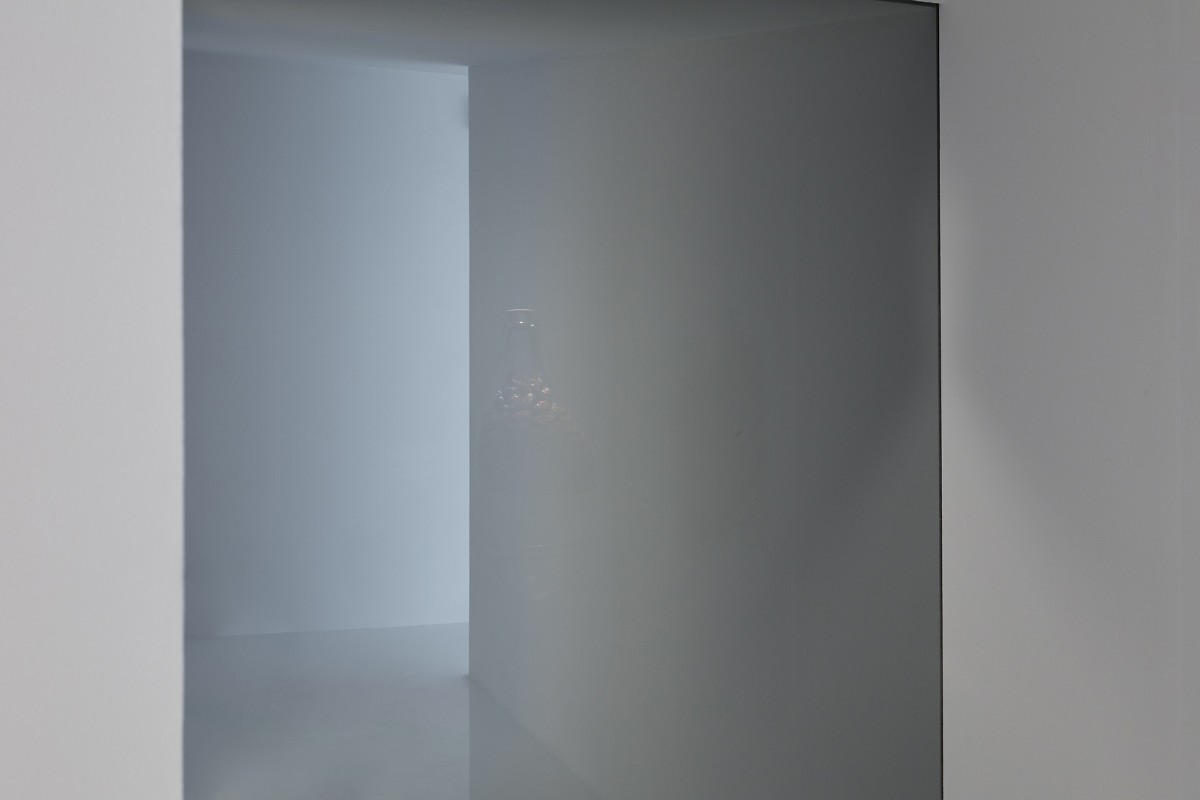

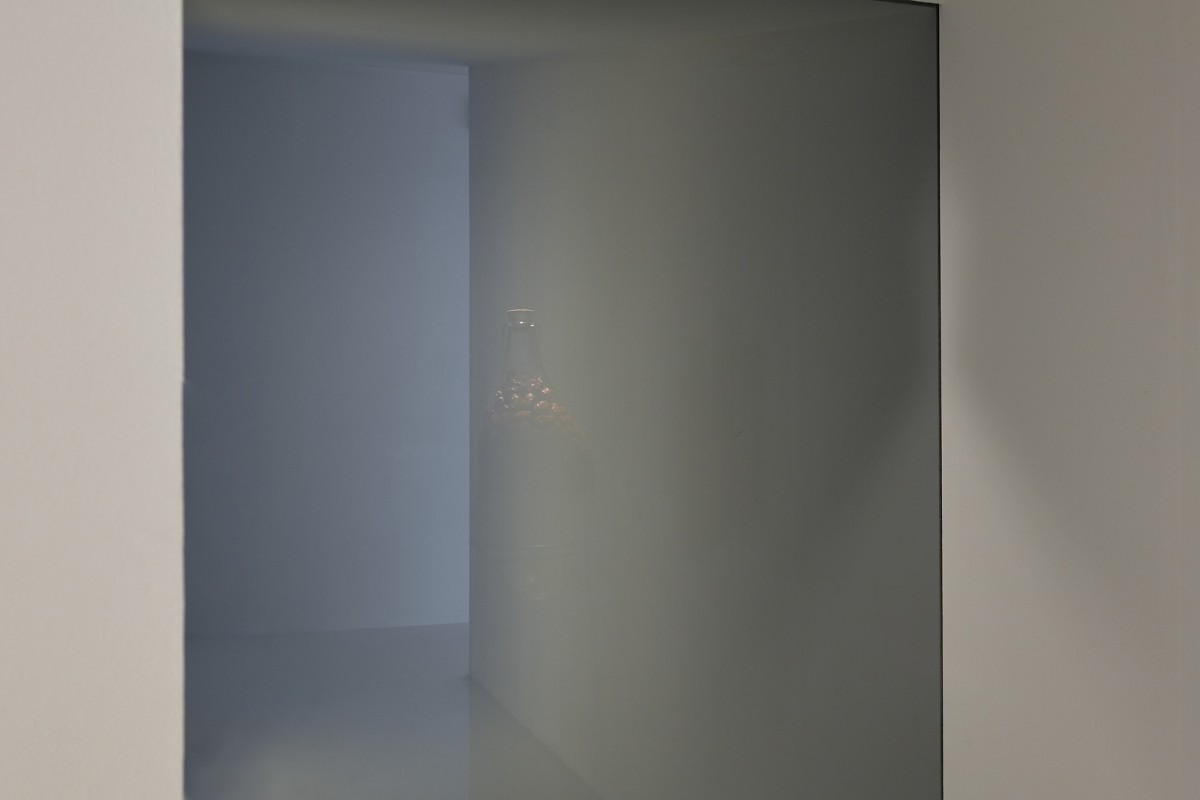

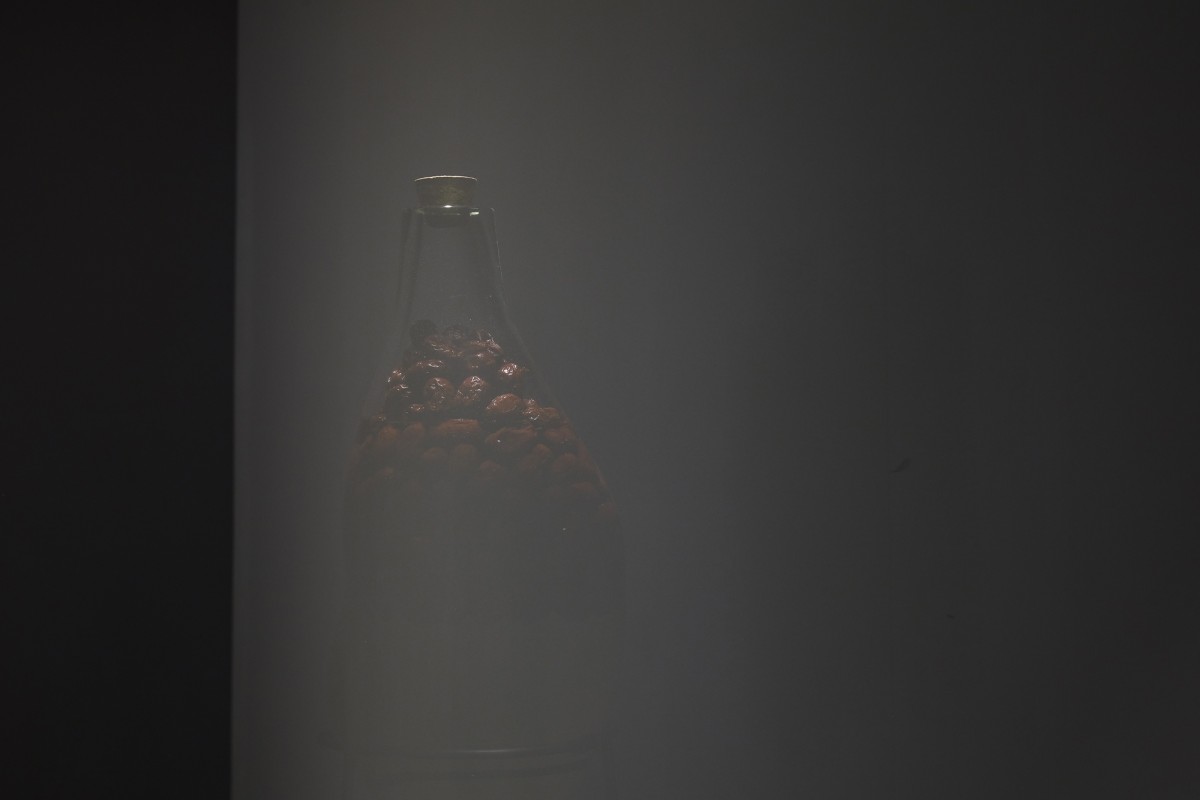

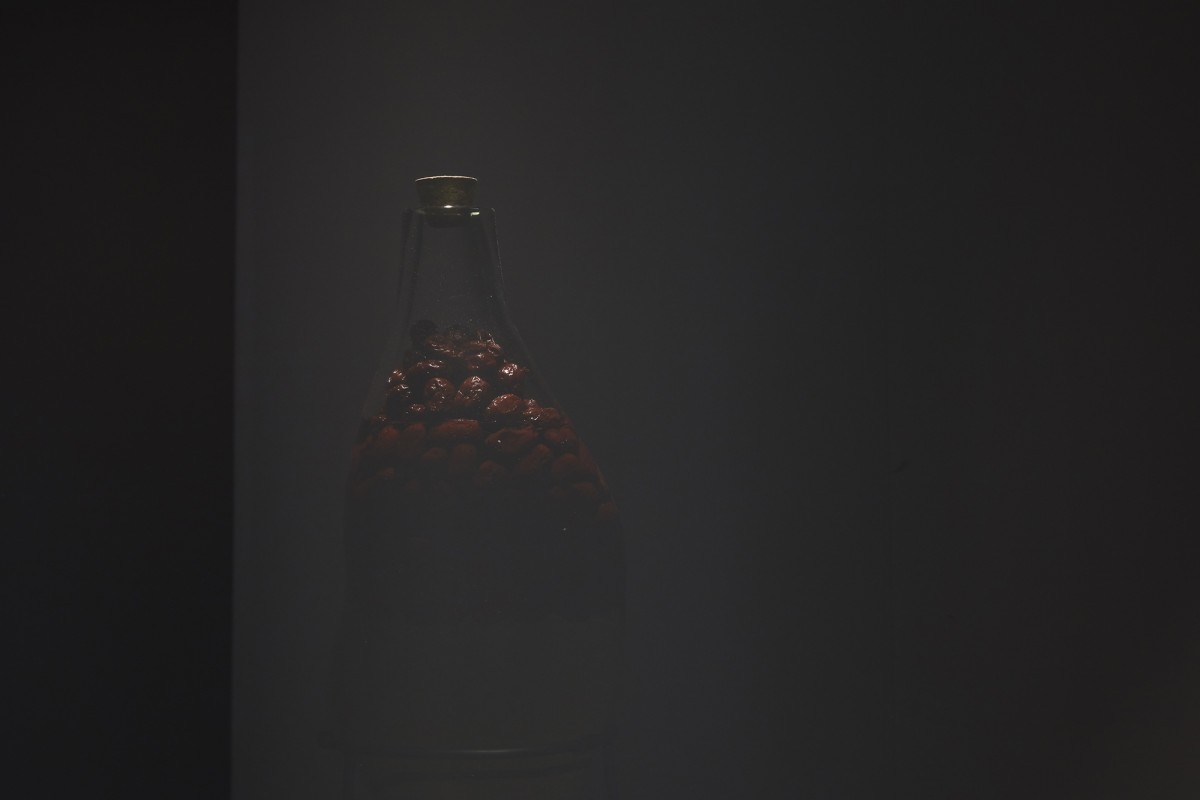

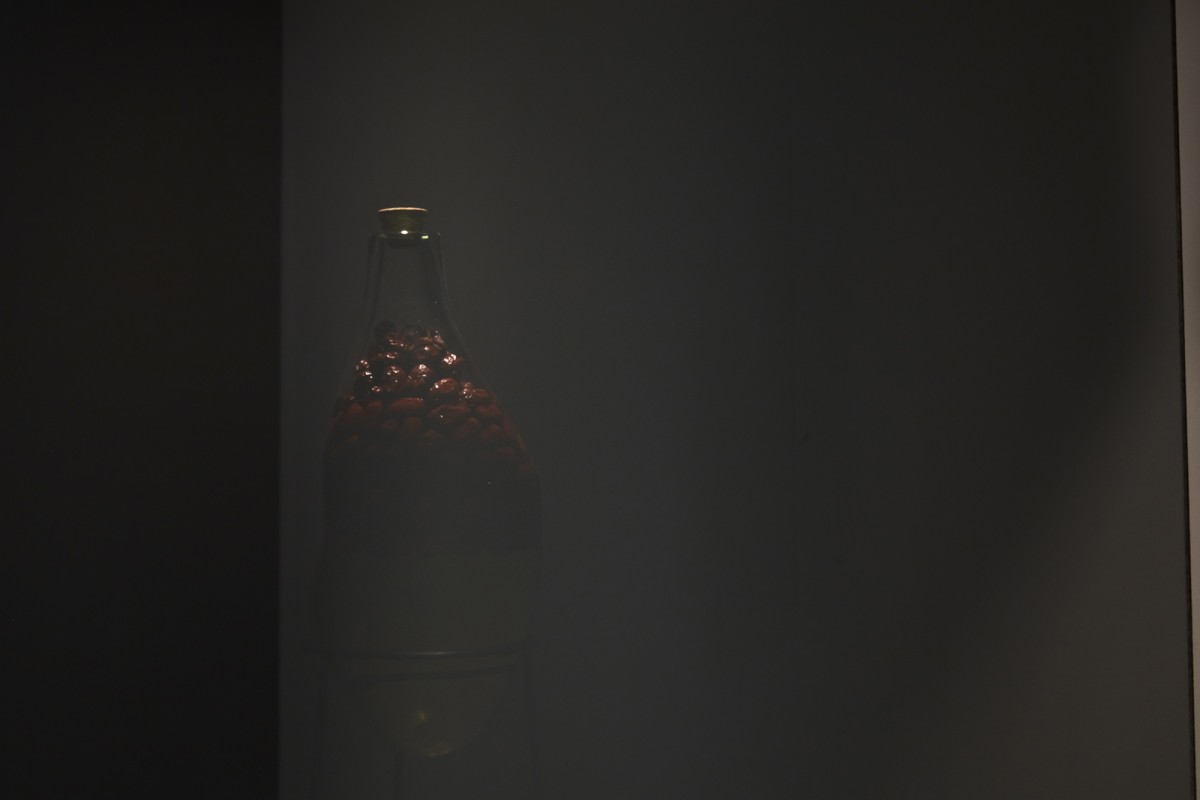

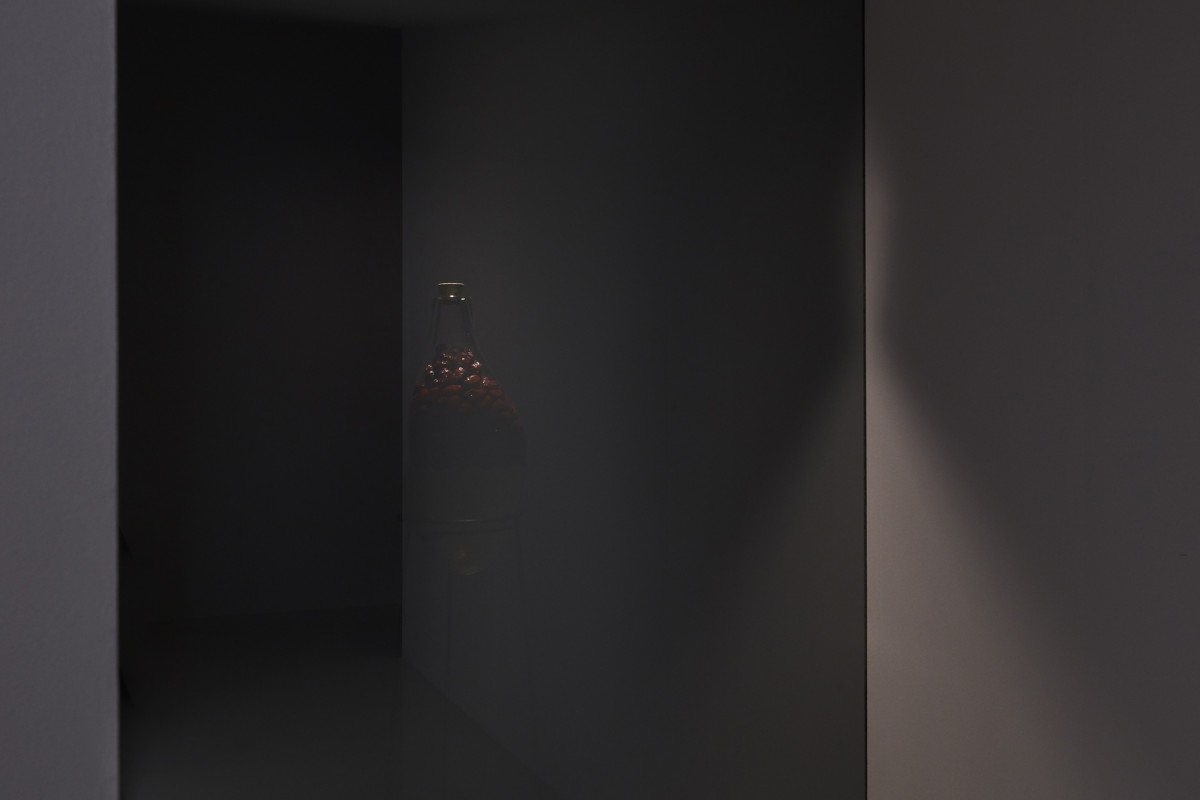

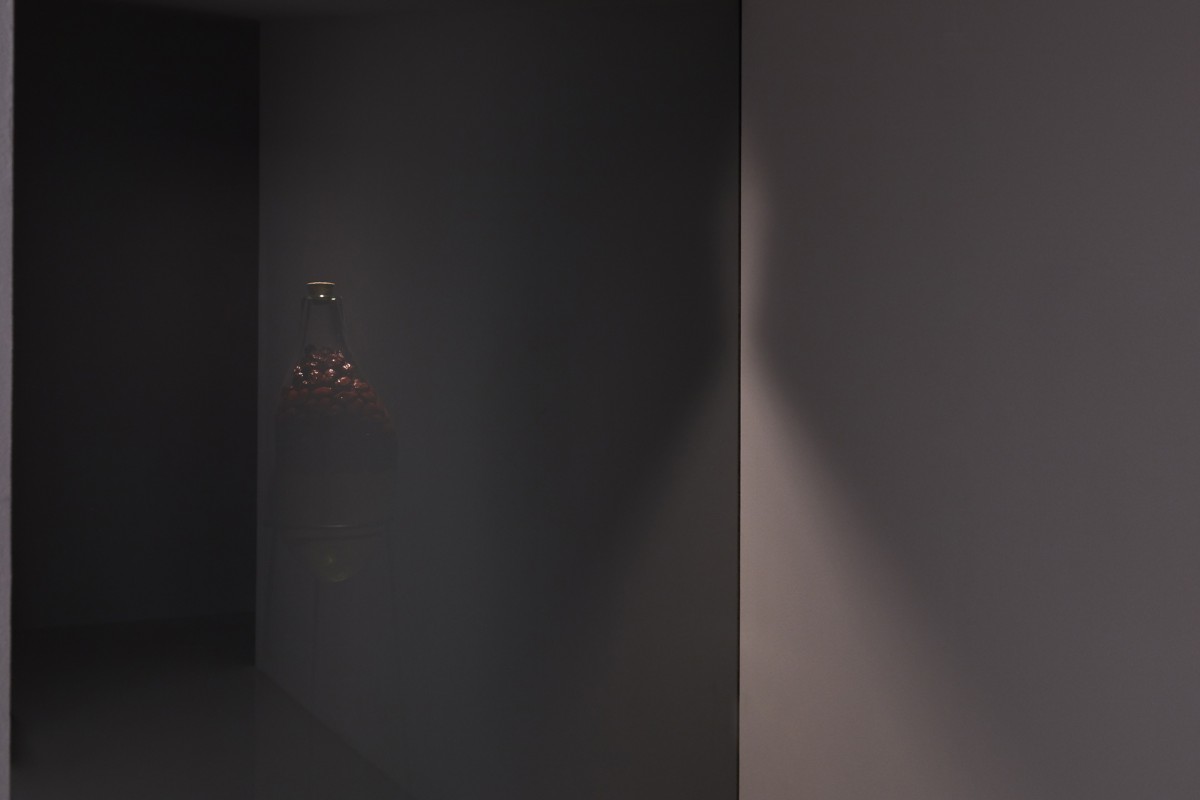

The blown glass bottles in which the liquid of for getfulness macerates are an attempt to materialize the shape of the glassmaker’s breath. The irregular, organic forms are all similar, yet each has its own identity. Suspended behind a one-way mirror, the bottle placed within the scenographic installation is visible at times, caught between the reflection of the mirror and its transparency.

-

I.

-

II.

-

III.

-

IV.

-

V.

-

VI.

-

VII.

-

VIII.

-

IX.

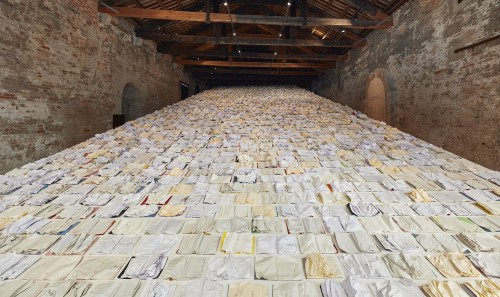

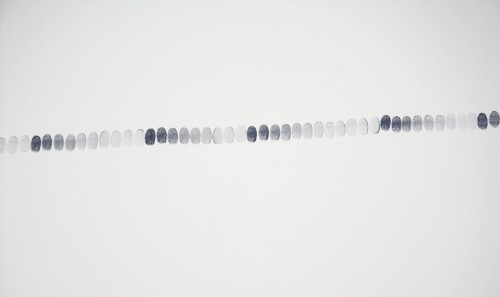

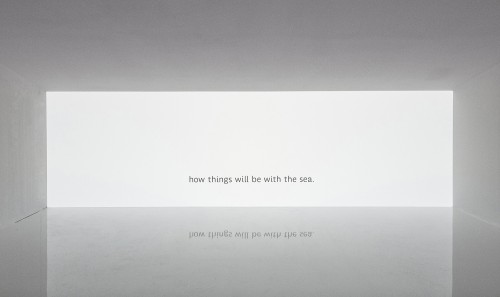

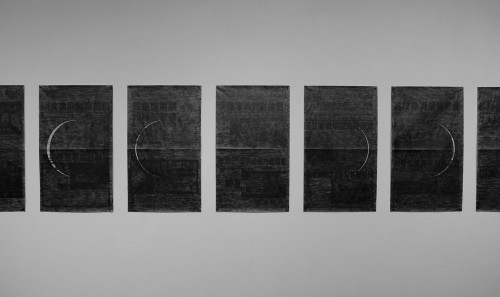

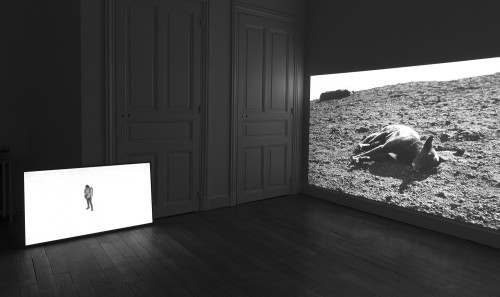

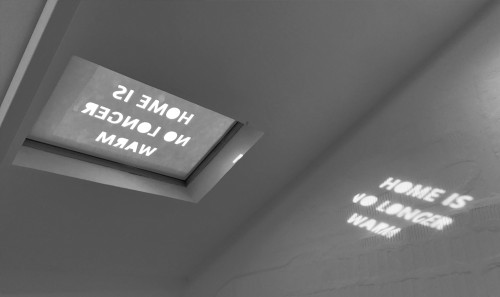

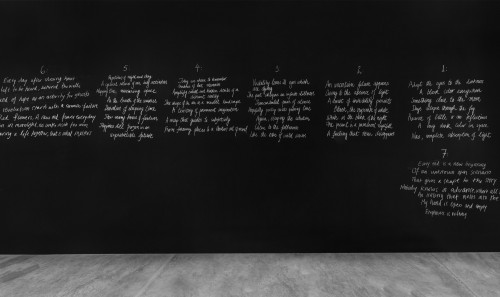

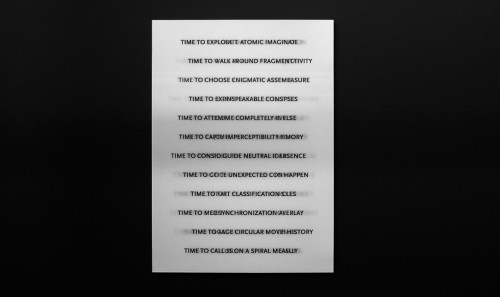

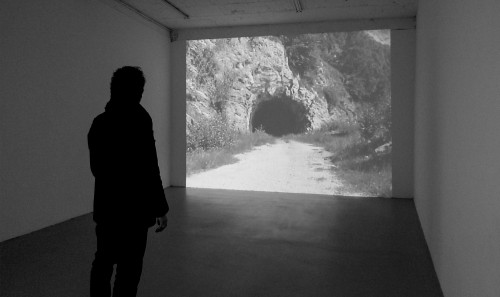

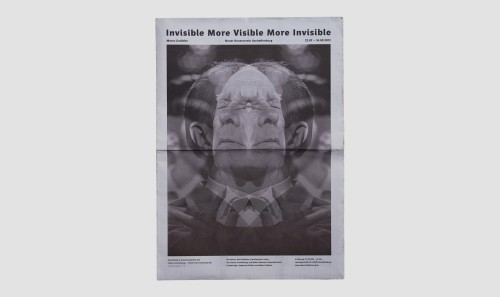

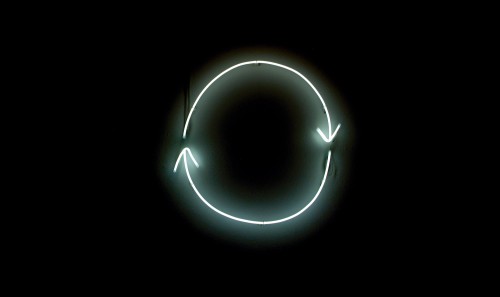

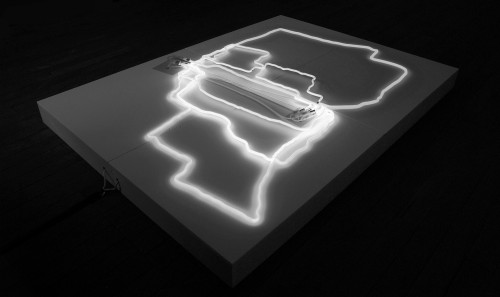

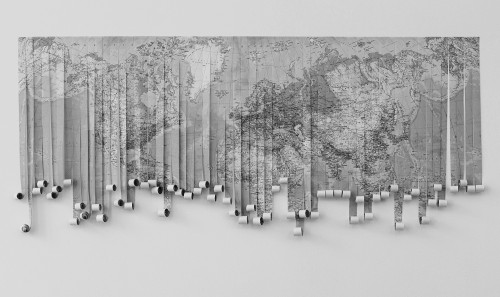

Installation views of the Luxembourg Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, 2019. Opening ceremony.

-

X.

-

XI.

-

XII.

-

XIII.

-

XIV.

-

XV.

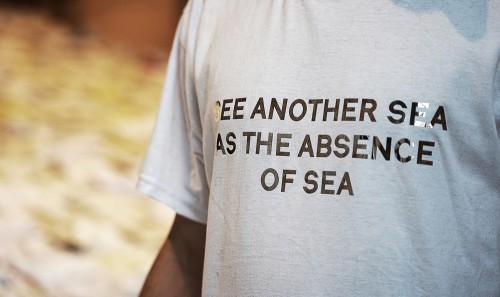

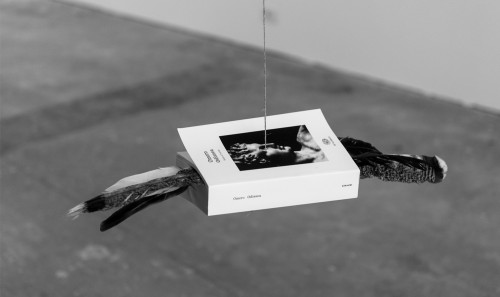

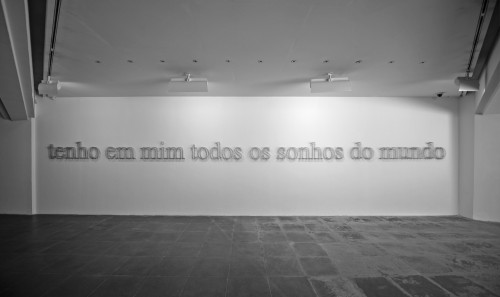

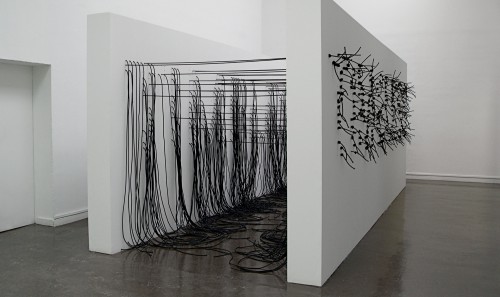

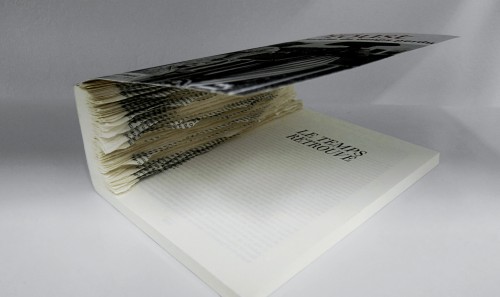

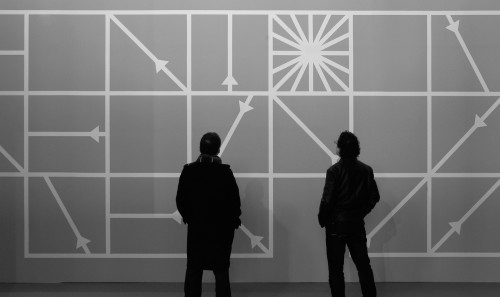

Performance views, Casino Luxembourg – Forum d’art contemporain, Luxembourg, 2019. Ending ceremony.

-

XVI.

-

XVII.

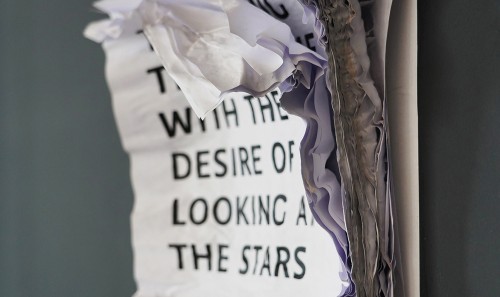

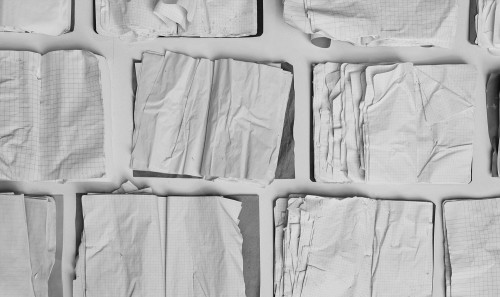

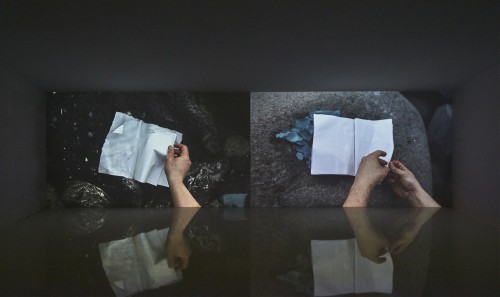

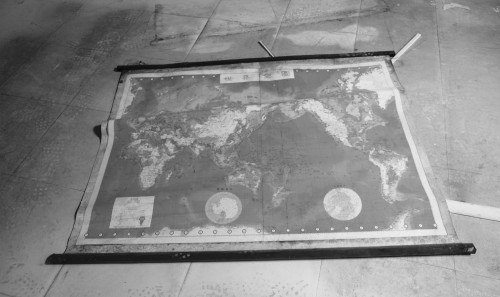

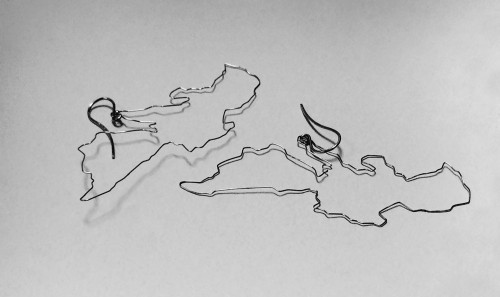

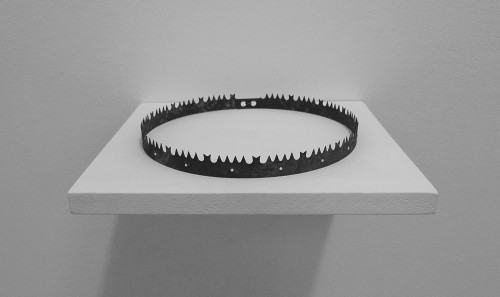

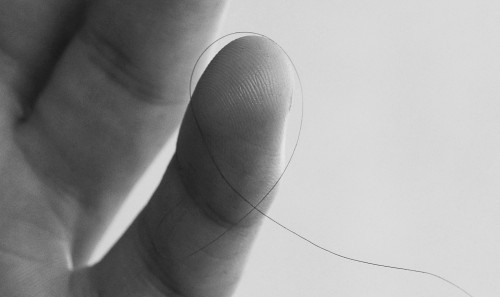

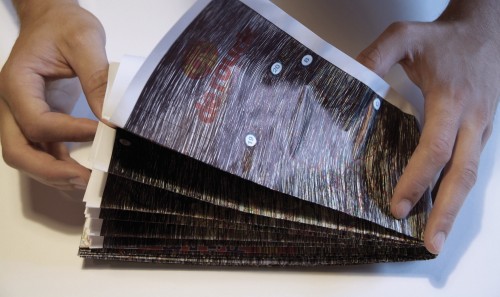

The breath and the hands of Stéphane and Paolo during the preparation of the project.

Installation views of the Luxembourg Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, 2019. Opening ceremony.

Performance views, Casino Luxembourg – Forum d’art contemporain, Luxembourg, 2019. Ending ceremony.

The breath and the hands of Stéphane and Paolo during the preparation of the project.