Reader-Traveller

Léa Bismuth

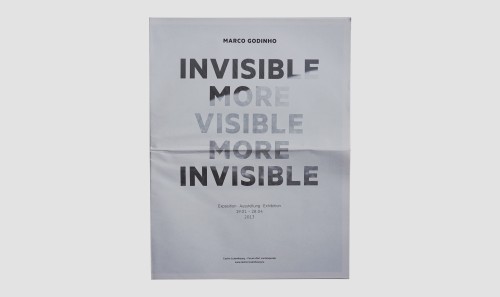

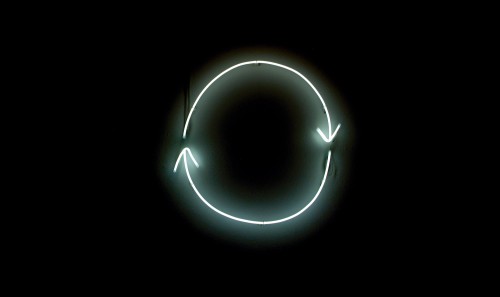

Reading and travelling. These two acts may well proceed from the same way of moving, of being able to engage in dialogue with a landscape, a geography, and to make our trajectories mindful, which is to say, always inhabited and habitable. Marco Godinho’s work proceeds from this dual tension: books accompany him. If he draws on them to extend his practice, it is in order to better see, to make visible, to traverse, to position himself, to turn around and go forward. For the past twenty or so years, his approach has been in progress, progressing in life while pursuing a career path, a strategy of taking in and conquering territories to come, those on which one can set foot but also those which remain unassignable, forever deterritorialized.

A Bookish Encounter

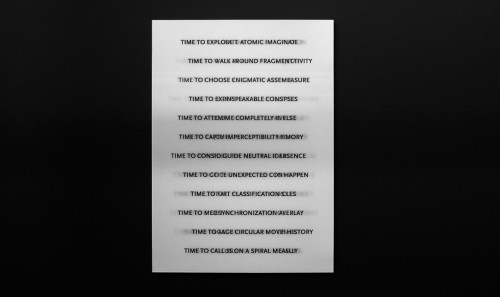

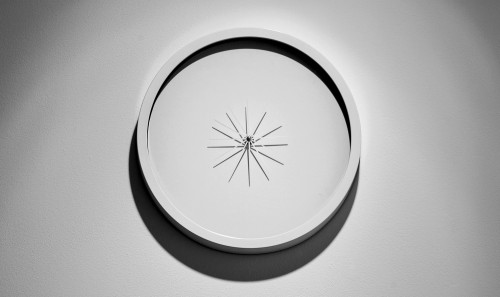

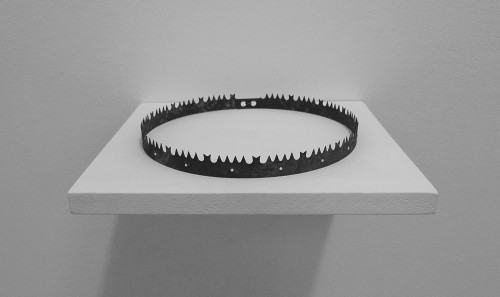

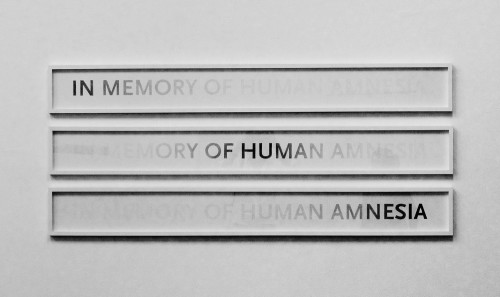

I met Marco for the first time in 2014, at the Art Brussels fair. We struck up a conversation that has continued ever since. That day we talked about Time and its passage, about Memory and the irreversible. I remember that Chronos was smiling at us from the corner of his eye, that a clock was rotating, and that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights had been copied onto a single grid to the point of making it illegible. I remember an eye hungry for knowledge.

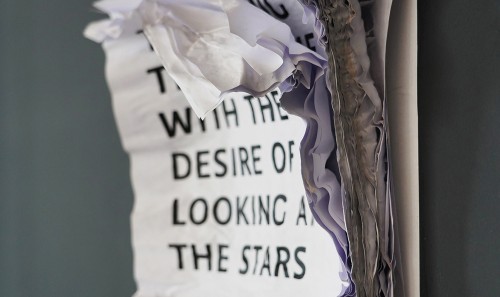

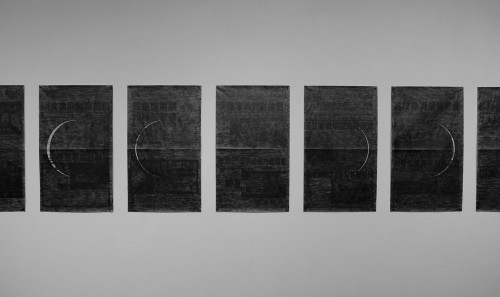

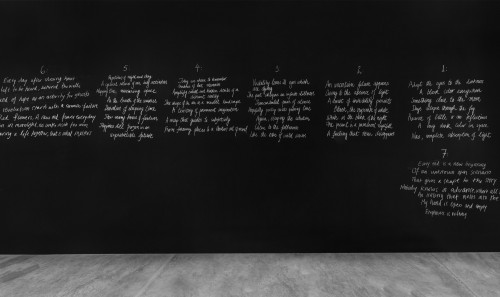

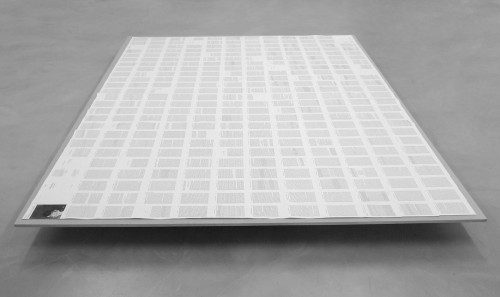

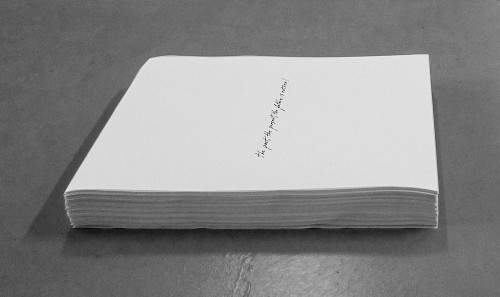

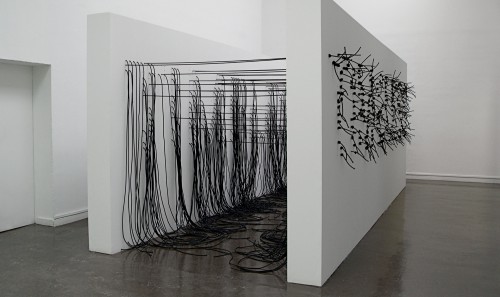

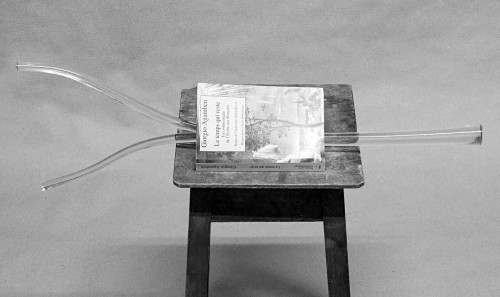

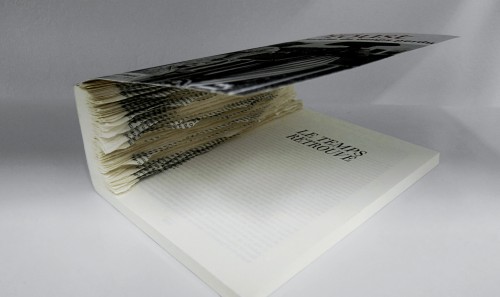

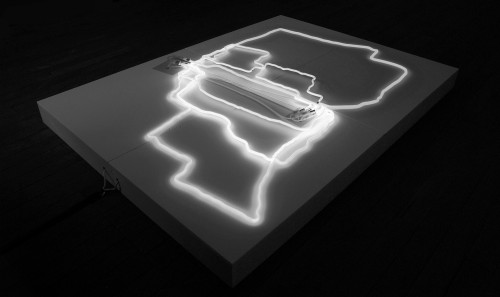

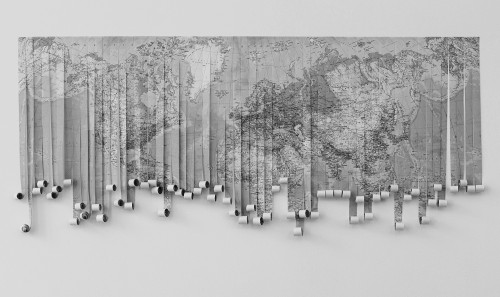

Soon I felt the urge to see this artist again, with his black hair and extraordinary gift of gab. I wrote to him a few days later, proposing an exhibition: “Do you want to create a work based on a book by Aragon dear to my heart, Blanche ou l’oubli?” The response was immediate, a form of acquiescence that ratified our initial discussion, giving him a possible space of shared action. Marco read the book. I understood later that he is a real reader, which is quite rare. I had chosen Blanche because it had exerted a strange power over my unconscious, my time had surrendered to it, my dreams engulfed and my critical faculties exhausted between the pages. I wanted to share it in order to rid myself of that fixation. Marco helped me do this, in that he spread out the book to its full length, completely unfolding it to create the talisman that would deliver me. His work was a carpet of meaning unfurled in the gallery space. The entire little Folio edition lay there, dismembered, like a body suspended slightly above the floor, unwoven, unraveled, undone, stripped of its leaves, forming a sea of pages sewn together in a sort of textual cartography. The pages of Marco’s copy were full of his penciled annotations and underlinings. His readerly attention was captured there as if in the net I had cast for him, and to which he had responded.

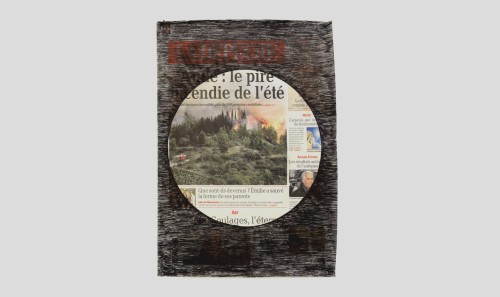

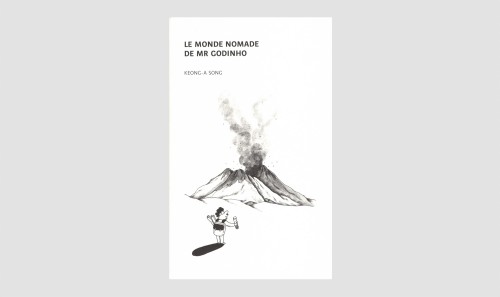

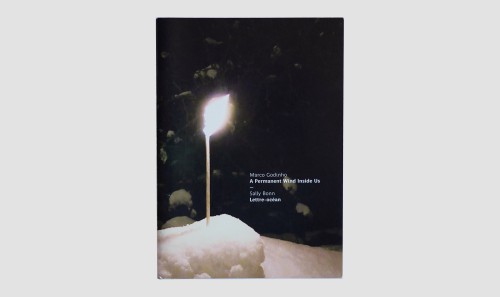

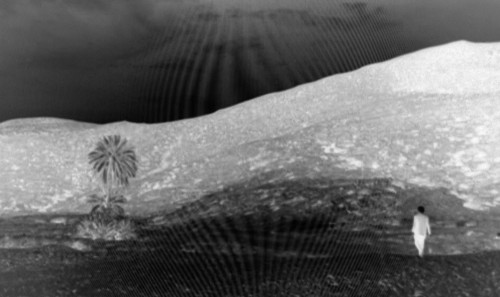

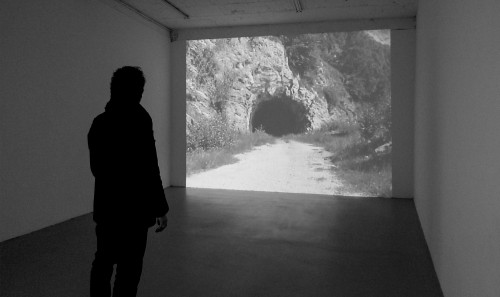

A few years later, we repeated the process with Georges Bataille’s Inner Experience, another book I treasure and had wanted to give to the artists. This time, Marco, accompanied by a character and a few stray dogs, took the book up Mount Etna on a cinematic trek to the partially snow-covered summit of the deserted volcano, searching for a philosopher of antiquity (Empedocles) said to have thrown himself into the crater in a quest for a form of truth. There Marco scattered the book, reduced to confetti, into the empty sky of a godless world as a sacrificial offering, in a conscious deployment of the gesture’s limits. He walked on the volcano with the book, he consumed it and opened it to the four winds. This was also a communication strategy involving volcanic energies, since messages in haiku form were sent by SMS during the climb, leaving the technological tool to engage with Etna’s ancestral entrails. These poetic messages were later laser-cut into the picture side of used postcards of Mount Etna bearing the greetings of earlier pilgrims, which the artist purchased online. In this way, the cards served to obtain a new disappearance of text by fire. “Your silence is my voice exiled in the dead of night,” reads one of them.

I am speaking of encounters with books, when the books also allow wandering souls to discover themselves on a few lines of flight, in the interstices of concepts and feelings. Have you ever had the feeling when reading a book that you are reading your own thoughts, that you are reading something you had not known about yourself but which someone had already formulated, about you, long before your birth? It can happen (rarely, but it does) that this feeling is sharable. In such case, we would speak of a community of readers, which is the surest and purest of friendships.

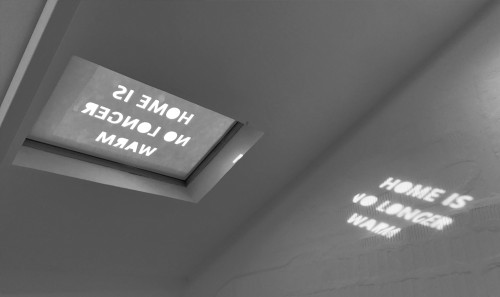

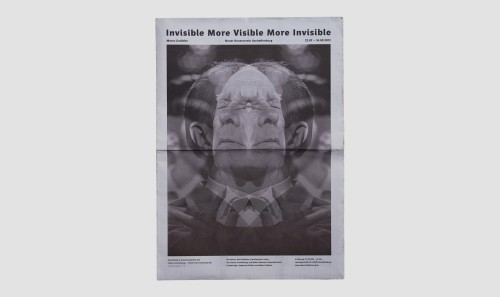

My Library Will Be with Me Everywhere

Then I think about a man who was a philosopher, writer, exile, existential poet, a man who paid the ultimate price (his life) for his intellectual independence. I think of a man whose life as reader and life as traveller were inseparable. I think of an Angel who one day, in a small room in Berlin, predicted to this man that he would be a writer; the Angel gave him his name. If I am thinking of Walter Benjamin here, it is probably because Marco somewhat resembles him. Not that he is Jewish, not that he is German, but as a Portuguese living in Luxembourg and making this dual origin the matrix of his travels and nomadism. When a person searches for the land that is his and no longer really has one, he wanders in geographical, geopolitical, geocritical limbo, beyond the borders, forever immigrant. He finds his place nowhere, on no map, and so he moves ceaselessly between borders in an attempt at peace of mind, a sort of reconciliation, in the zones where the flags remain transparent. His homeland is the one he chooses as a collector of places and books, a collector of quotations and lands. That man will never have a house, will never find a stable home, and his life will navigate from place to place, populated by languages, by faces encountered here and there, by small things captured and carried along in an imaginary suitcase that continues to swell. And yet this suitcase will never become a burden, because its weight is symbolic. That man will invent rituals, counterattack procedures, impossible archives; he will make pharmacopoeias and first-aid kits of his books. He will put in his immaterial suitcase everything useful to have in order to sur-vive, to live in superiority despite the lack, to live in an excessive manner despite the precariousness and the incommensurable loss of home ports.

That being so, reading and roaming become gestures that give life greater depth, and lend consistency and a kind of impetus to the work in the making. He who reads and collects his readings creates his own constellation. This practice, then, is a powerful technology of the self constructed like a tailor-made critical apparatus. The collected readings are material in which to forage, the way a bee drinks a flower’s nectar to make its honey. The quotations that Marco carries everywhere, in his suitcase light as oblivion, are drawn from Franz Kafka, Jorge Luis Borges, Jacques Derrida, Édouard Glissant, Georges Pérec, Gilles Deleuze, Jean-Christophe Bailly, Kenneth White, Nicolas Bouvier. The list could go on, but already it seems to murmur of a secret fraternity of unaffiliated thinking, of outbound geographies, of expanded voyages, of thresholds and griefs, of broken and deterritorialized lines, of spatial poetics. These books are songlines, as in the title of a Bruce Chatwin book the artist values and on which he drew to create The Last Sentence of the Book, copying in pencil the final words of this work devoted to aboriginal cultures: “They knew where they were going, smiling at death in the shade of a ghost gum.”

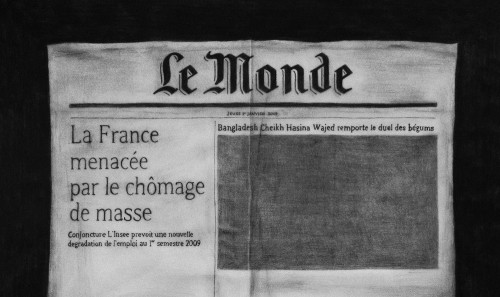

The Song of an Odyssey

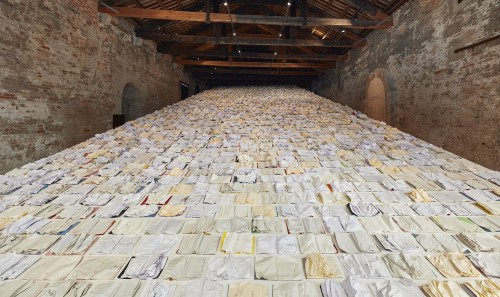

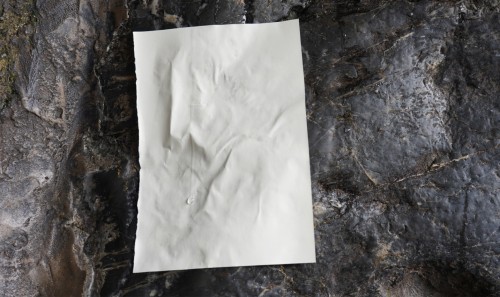

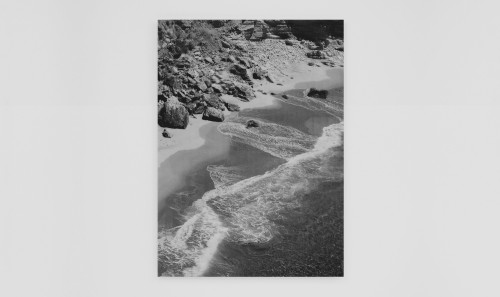

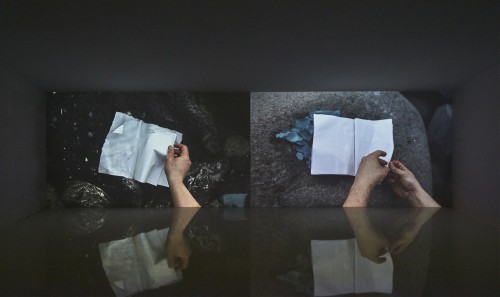

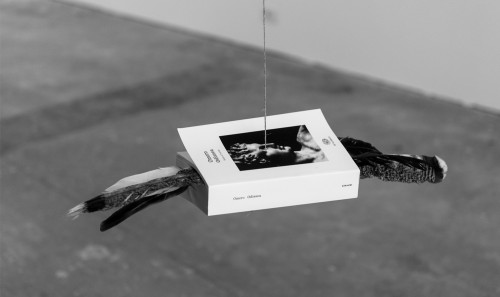

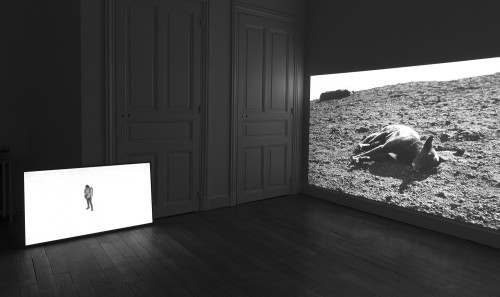

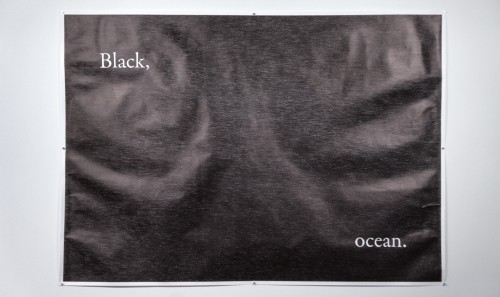

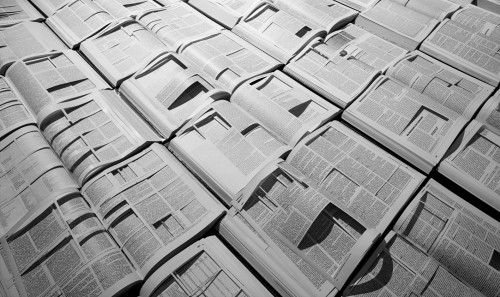

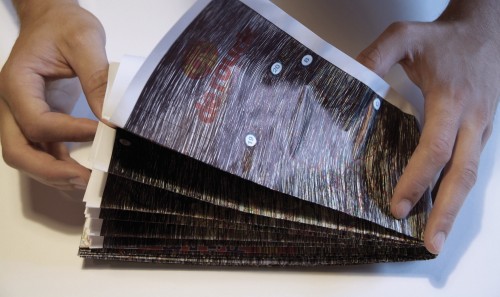

For the installation Written by Water, presented in the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, it was Homer who guided the artist as he journeyed around the Mediterranean rim, accompanied by the Odyssey. What could be more fitting? Is the Odyssey not the epic that would become travel narrative itself, in other words, the exemplary vector of all literature? For literature is just that: a journey, a setting in motion, an effective point of departure (Troy), a hoped-for point of arrival (Ithaca); and between the two, wanderings and encounters, torments and abysses, experiences and epiphanies. Such is the Ulyssian voyage that Marco restages, replays, in a venture that rethinks the meaning of the migrations our contemporary world is witnessing, aghast. For this project, he undertook an action (Left to Their Own Fate) consisting of three initiatory journeys (Strait of Gibraltar/Tunis, Carthage, Djerba/Trieste and Istria) during which his brother, Fábio, silently read all three volumes of the complete text of the Odyssey: once read, each page was dispatched to the sea, in a gesture of dissemination, toward the souls disappeared in the Mediterranean. The reading was thus an actual enactment by the reader as cantor of an age-old expression and spokesperson of a sea peopled with corpses swept along by History.

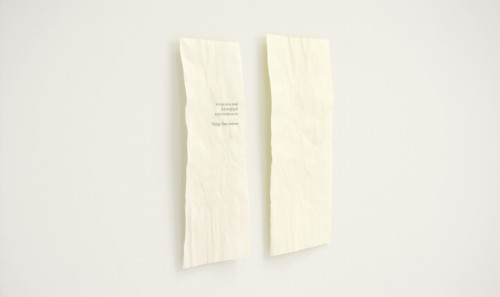

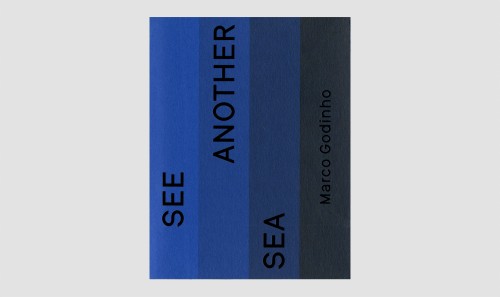

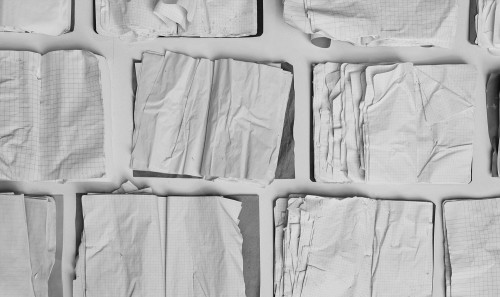

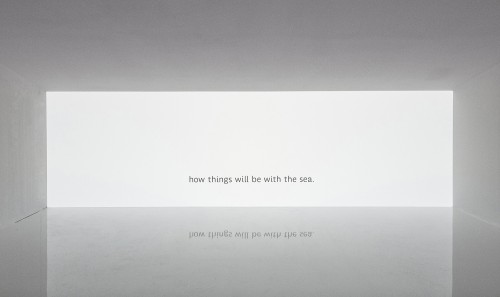

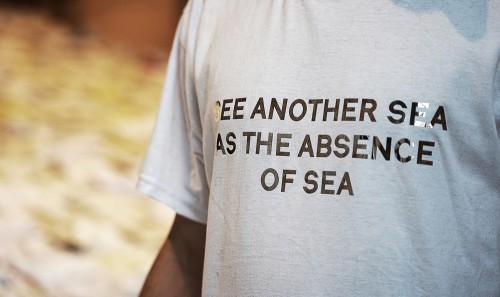

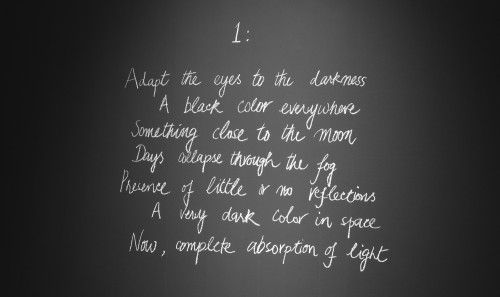

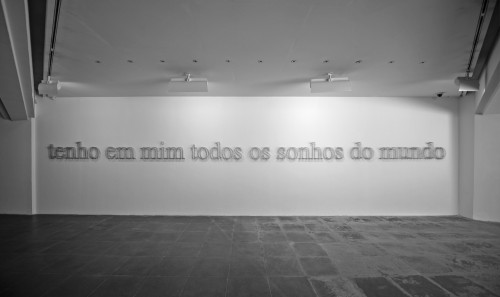

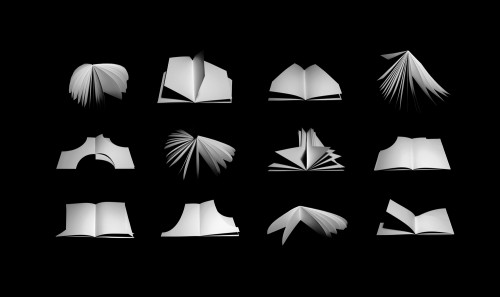

Reading is also an actual operation of restitution, a story of ghosts and dialogue. But it turns out that any authentic reading, especially if combined with a voyage that resurrects it in a lived landscape, is also a writing: writing reading can take many forms, including plastic ones. This is why Marco asked the Mediterranean Sea to write invisible narratives, by immersing in it blank notebooks that the tide would come to fill with a new poem. The notebooks became his library as well, but a library no longer in need of quotations and blackened pages. The foam sufficed, and the trace of its passage on the white pages. Hundreds and hundreds of notebooks written by the sea form the roof of the immersive structure (house or cabin) in the Luxembourg Pavilion at the Venice Biennale: it is an organic sculpture that visitors can enter, an architecture, an arch, whose roof is a canopy of student exercise books. However, the poem See Another Sea gives the white writing a voice: composed of 201 verses (one for each day the pavilion is open to the public), the song, this time, is that of the artist himself. For, as Barthes asks, “How is it possible to read without being bound to write?”

Hence, reading-travelling-writing, these three acts are simply a constituent and irreducible triad. These are the first and last lines of the artist’s daily-renewed song: See another sea as the absence of sea / See another sea in the wind that blows without a noise. The voyage seems to end, yet never totally ceases. Many murmurs remain suspended, the rustlings of that which has disappeared and sunk but which we can awaken. Marco Godinho’s work embodies a form of invitation to see another sea, and still another; seeing another sea disappear and reappear; seeing other exiles and other enthusiasms, other impulses surpassing that which cannot be surpassed, ignoring the obstacles, celebrating the solar and lunar energies, reinventing passages.

Léa Bismuth is a writer and art critic. Her practice mixes literature and contemporary art and explores possible ways of writing about exhibitions, from essay to narrative. She has contributed to artpress since 2006. With a background in philosophy, she initiated the curatorial research program La Traversée des Inquiétudes, a trilogy of exhibitions inspired by Georges Bataille and produced between 2016 and 2019 at Labanque, in Béthune (France). Since 2013, she has curated some twenty exhibitions in France, including for Le BAL in Paris, Les Rencontres d’Arles, Les Tanneries in Amilly, Drawing Lab in Paris and URDLA in Villeurbanne. In 2019, she published La Besogne des images with Éditions Filigranes, Paris, and co-curated the exhibition Dans l’atelier la création à l’œuvre at Musée National Eugène Delacroix, in Paris.

- I refer here to two works, Time to (...), 2014 and L’irréversible, 2014.

- The Abyss of Chronos, 2014.

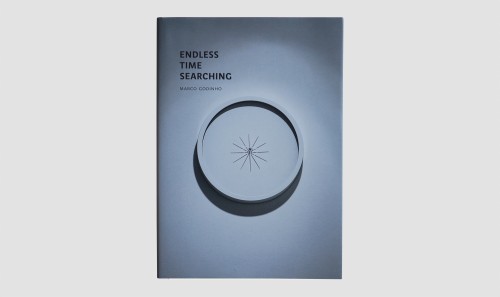

- Endless Time Searching #3, 2008.

- Allgemeine Erklärung, 2013.

- For the exhibition Blanche ou l’oubli, Galerie Alberta Pane, Paris, 2014 (curated by Léa Bismuth).

- For the exhibition Intériorités, the second in La Traversée des Inquiétudes, Labanque, Béthune, France, 2017 (curated by Léa Bismuth).

- Character played by the actor Fábio Godinho, the artist’s brother, later seen in Written by Water.

- See, in this regard, the video Notes on this earth breathing fire (Gesture of offering).

- See, in this regard, the multiscreen video installation Notes on this earth breathing fire (Climbing the slopes), 2017.

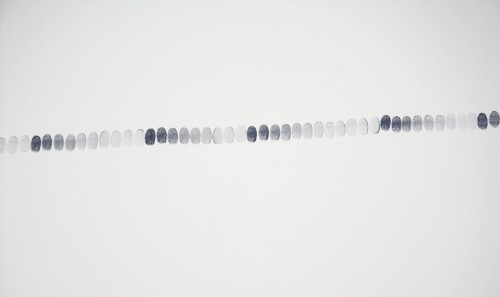

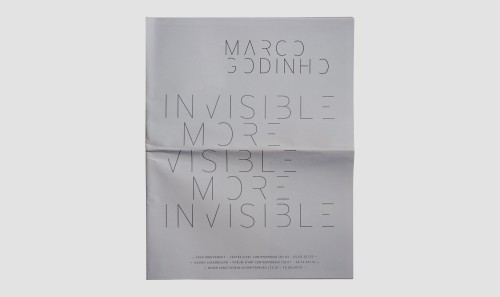

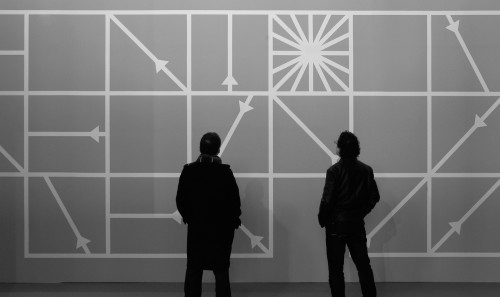

- I refer here to an adaptable in situ work made with an ink stamp, which the artist has produced several times: Forever Immigrant.

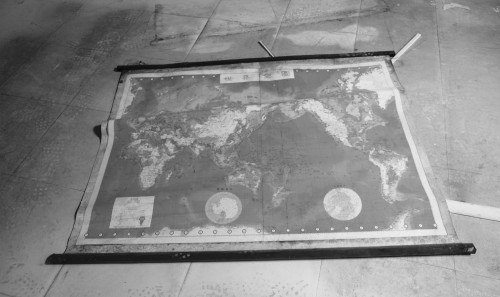

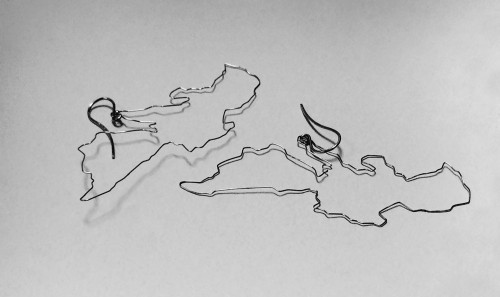

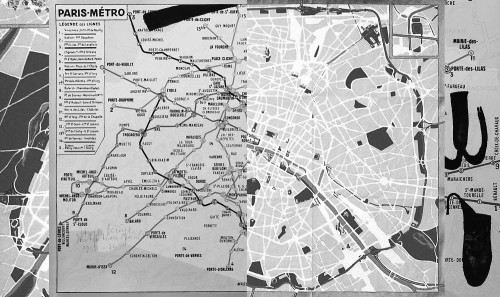

- In GR #1-4 (2007), Marco Godinho reinterprets a map showing the territorial identity of the Greater Region – so named by a political agreement among four regions located in the heart of Europe: the German Länder of Saarland and Rhineland-Palatinate, the Lorraine region of France, Wallonia, the French Community and the German-speaking Community of Belgium, and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg – in a contextual displacement. The artist covered over four of these maps with the four basic colours (red, green, blue, black) of the famous BIC ballpoint pens.

- See Untitled (Transparent Flags), 2007-2011.

- Roland Barthes, The Preparation of the Novel [1978-80], trans. Kate Briggs (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 139.