Hoping for possibilities, at every instant

Christophe Gallois

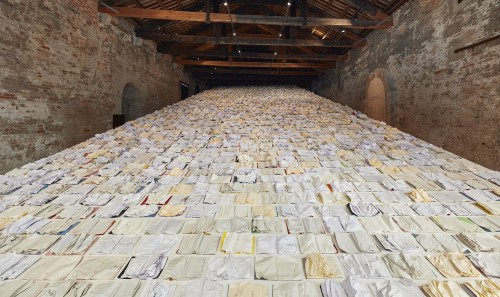

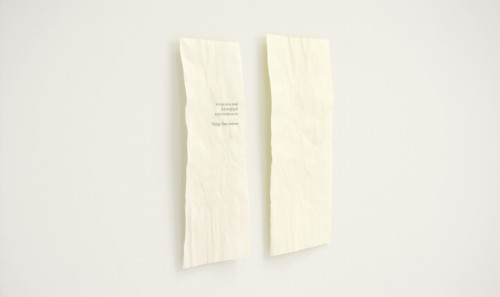

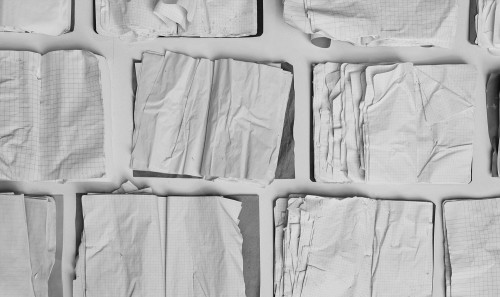

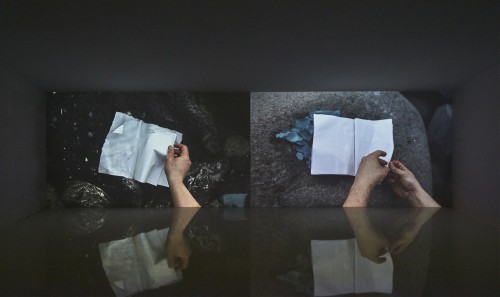

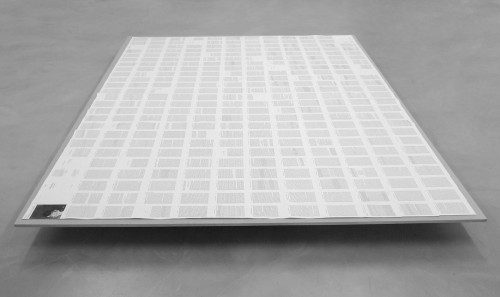

“On my journeys, I immerse blank notebooks in the sea, allowing each page to absorb and be infused with the water’s memory.” This is how Marco Godinho described Written by Water, the collection of notebooks “written by the sea” he had been steadily producing since 2013, as he stopped in cities and on islands around the Mediterranean basin. Palermo, Lampedusa, Catania, Syracuse, Ceuta, Carthage, Marseille, Venice, etc.: cities and islands whose names are cloaked in a dense, often millennial, imagination and which, in some cases, embody the geopolitical issues, and too often tragedies, of which the Mediterranean is now the theatre.

This gesture of “modest simplicity,” become ritual over the years, was marked by motifs that have animated Godinho’s practice from the outset: travels, migrations, writing, erasure, geography, time. It was the way in which these motifs intersect, intertwine and interweave that interested me. In presenting the project for the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale, he suggested seeing images of time in the notebooks, “a fragmentary time, in which each page is a story.” Let’s open a few of those pages.

Evanescence

The time of Written by Water, is, above all, that of appearance and disappearance, of trace and erasure, of memory and oblivion, of ebb and flow, of surfacing, of evanescence. No stories run through the pages of these notebooks, apart from those brought and then carried away by the waves, diluted in the immensity of the sea or evaporated once lifted from the water. But on the surface of the pages, in the traces they contain, in their ripples and their meanders, deep in their folds, thrives a space of possibilities, of potentialities, and an open, indeterminate time, where the past melds with the future, where memories couple with portents.

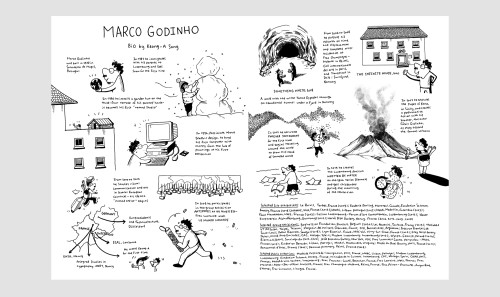

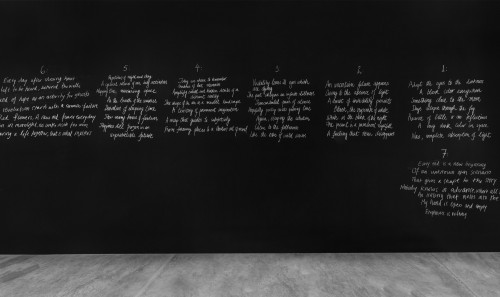

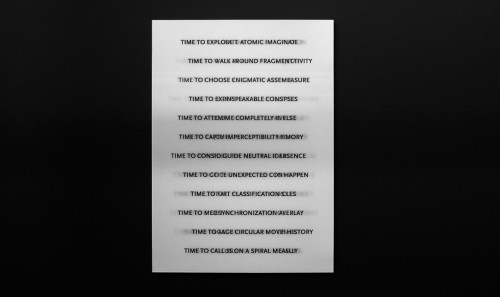

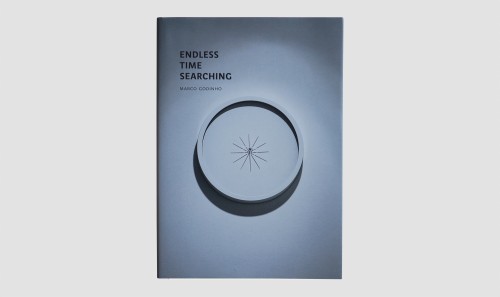

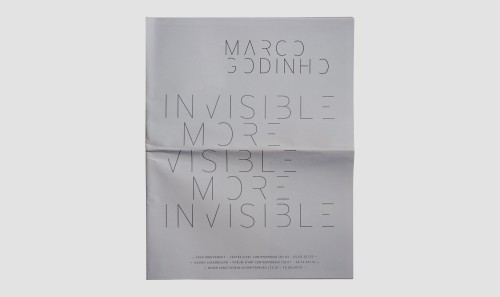

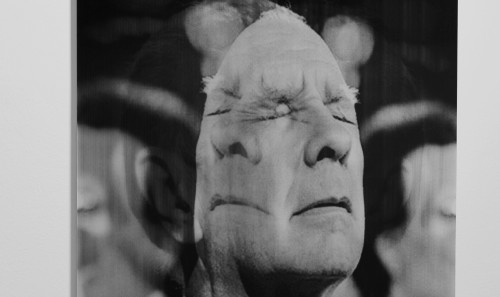

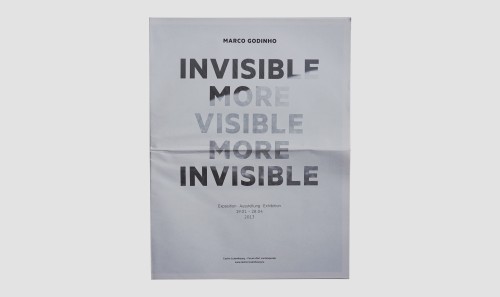

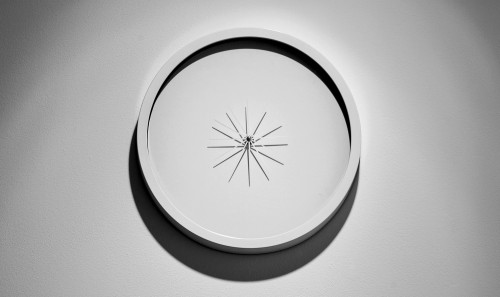

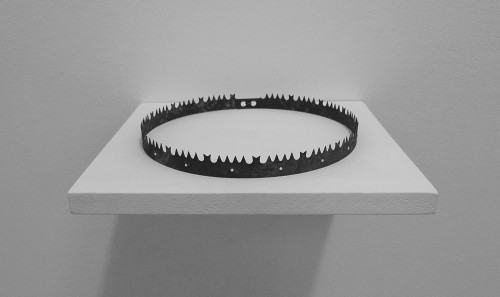

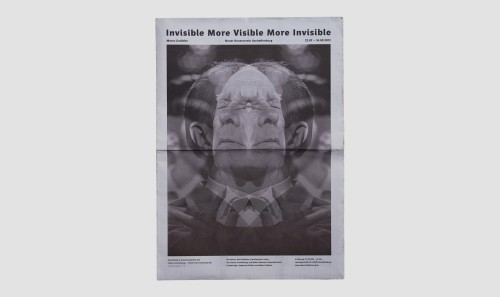

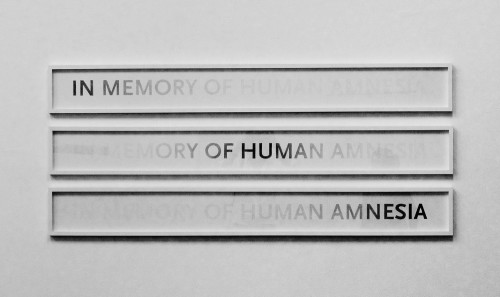

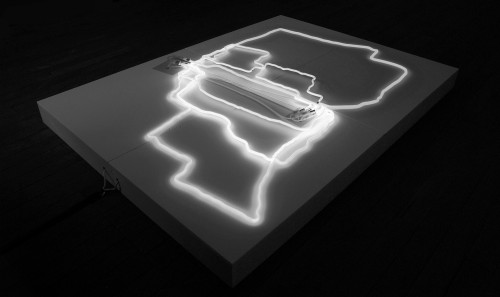

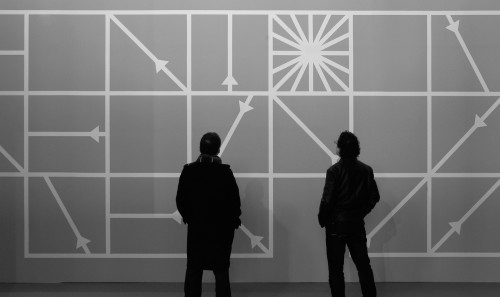

This territory of possibilities, where erasure leads to the greatest openness, where imperceptibility meets immensity, was explored by Godinho very early on, in his initial works. A look at the titles of a few of them suffices to measure the expanse of the temporal imagination that his practice deploys. Endless Time Searching #2 (2008): a series of drawings made directly on a wall by tirelessly repeating the same circular gesture until the graphite pencil completely wore down. In Memory of Human Amnesia (2008-2009): three drawings in which the title words, written three times in different gradations, oscillate between appearance and disappearance. À l’infini (2007-2009): a frieze composed of sixty-five photographs in which the artist records the unexpected (in everyday life) appearance of the symbol signifying infinity (∞). The title he gave the exhibition he had in 2013 at Casino Luxembourg, Invisible More Visible More Invisible, best renders the back-and-forth play of his works between the imperceptible and the tangible, two worlds on whose margins his art lies. More recently, on the floor of the same institution, he created Remember What is Missing (2016), a “carpet” of dust collected at various abandoned or construction sites. “Time,” in his words, “resembles these steps that are going to go through the work and carry this dust with them. We are then in the presence of a space of transition, of passage, of permanent flux.”

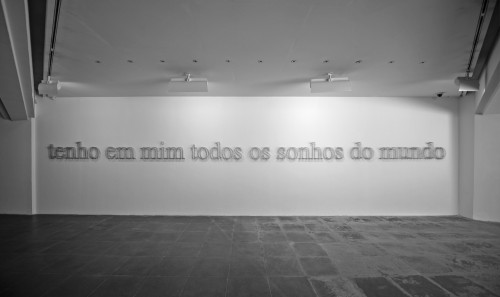

Godinho’s works seem to explore what Fernando Pessoa, who figures prominently in the artist’s literary imagination, termed “the visible enigma of time.” They simultaneously evoke the essential temporality of our existence and the feeling of its unreality. “The past, the present, the future is not real,” he wrote in a poem titled (…) is not real (2013). Might this unreality of time be the fertile ground for the subtle melancholic longing – the saudade – that seems to emanate, discreetly, from some of his works? “I am nothing. … Bar that, I have in me all the dreams of the world,” reads another line by Pessoa, which Godinho borrowed for a 2007 installation: Tenho em mim todos os sonhos do mundo. This phrase could be the credo of every one of his works, of the space of possibilities that unfold there.

Cycle

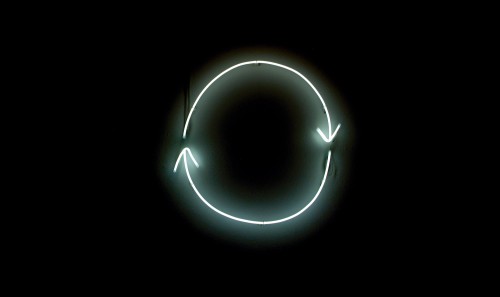

In an interview I conducted with the artist in 2017, he explained, “I do not see time on the model of the timeline, on which each of us walks, grows, then dies, where what has happened is behind you and where we never go back to the same place, but that of the cycle, the loop, the constant return, correlated with space and paced by the seasons: it is thus that we regularly go back to the same place. It is this rhythm that conditions any lives.” The cycle, the loop, the succession of days and seasons set the pace of his work. Created in 2008, Endless Time Searching #4, materialized in neon in the form of a freehand drawing of the Internet symbol for “Refresh page” – two arrows forming a sort of temporal loop – announced this aspect of his oeuvre.

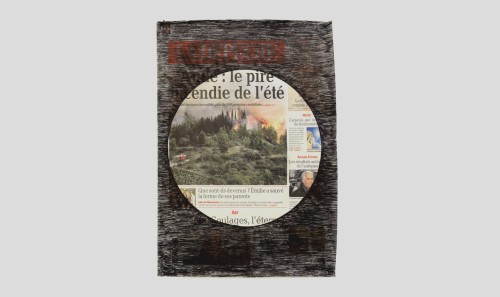

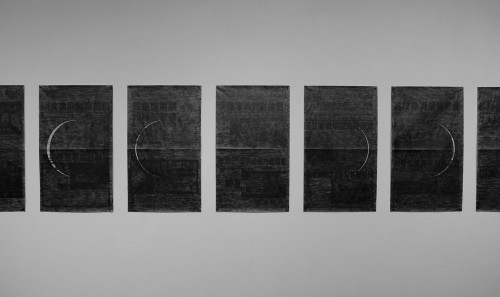

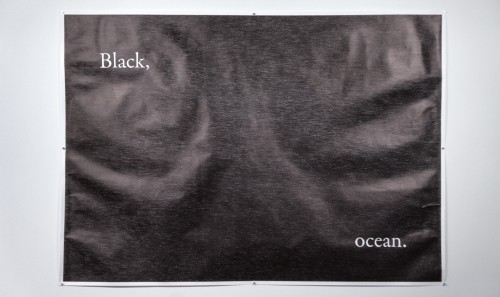

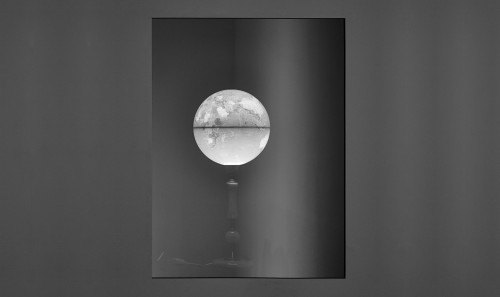

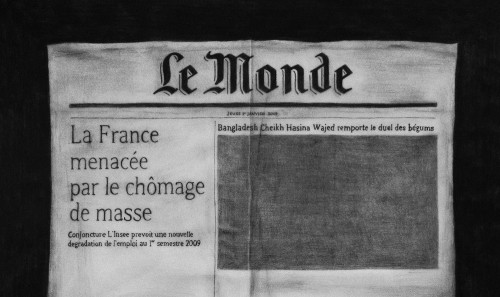

Reproduced on several occasions – in July-August 2017 in Italy, for an exhibition at Galleria Massimo De Luca in Mestre, in September-October 2017 in France, for an exhibition at Fondation Salomon in Annecy, and in April 2018 in Taiwan, for an exhibition at TheCube Project Space and VT Artsalon in Taipei – the series Lunar Cycle juxtaposes the temporality of the lunar cycle with that of human activity. Using the front pages of newspapers bought daily during the production period (the length of a lunar month), the artist blackened the paper with ballpoint pen except for the outline of the corresponding lunar phase. On each page, in the area representing the lit part of the moon, only a portion of the news remained visible.

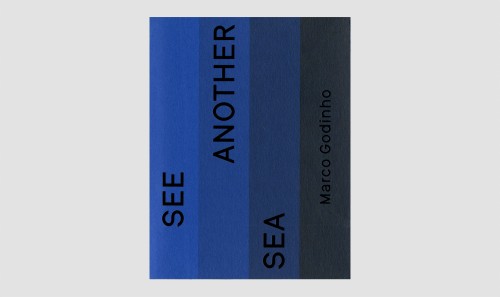

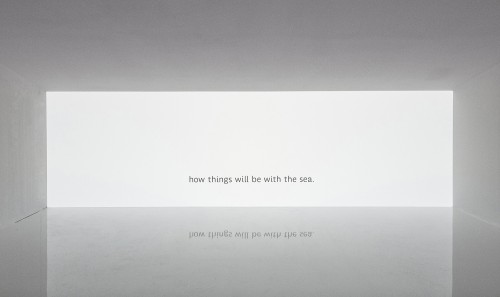

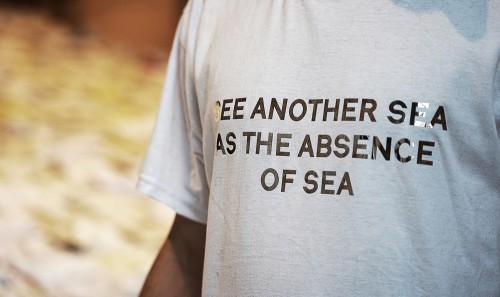

Other of Godinho’s works foreground the temporality of the exhibition itself. In 2012, Every Day a Revolution paid tribute to struggles for freedom in the form of a circle of empty bottles set on the floor into which, one by one, a single carnation was placed each day. Presented as part of his 2018 exhibition in Taipei, Every Day a Poem Disappears Into the Universe was inspired by a ritual observed in the city’s streets, where shopkeepers burn imitation banknotes as offerings in front of their stores. Godinho asked the gallery managers to burn a poem exhibited during the day each evening in front of the gallery. For his exhibition at Musée Pierre-Noël, in Saint-Dié, France, he asked the museum director to write a daily poem, delivered by text message, on the ground in front of the entrance. In Venice, the 201 verses of the poem See Another Sea (2019) appeared one after the other, day after day, on the T-shirt worn by the pavilion supervisor. Each verse meant to underscore the exhibition’s discreet rhythm, its life, its pulse, its breathing.

Mapping Time

In a text on Immemory (1997), an interactive work he created for CD-ROM, the filmmaker and artist Chris Marker wrote, “In our moments of megalomaniacal reverie, we tend to see our memory as a kind of history book. … A more modest and perhaps more fruitful approach might be to consider the fragments of memory in terms of geography. In every life we would find continents, islands, deserts, swamps, overpopulated territories and terrae incognitae. We could draw the map [from] such a memory.”

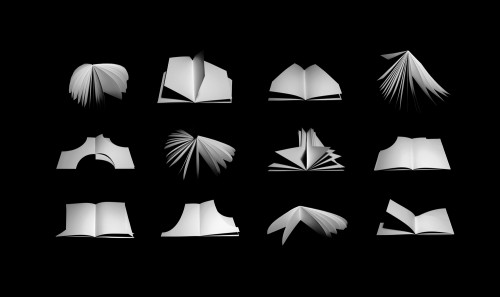

Like Marker, Godinho understands time in terms of space. Through his works, he sketches a “map of time where are intertwined non-linear stories,” a “map of a world shaped by personal, biographical and multicultural trajectories.” Freed from linearity, time becomes a territory to be roamed. Rather than being grasped, understood, mastered, it is experienced physically. It takes form in gestures, in travels, in the steps of walking, the practice of writing or drawing, the experience of reading, the movements of thought. The notebooks of Written by Water seem to visualize this spatial concept of time. In place of the narrative linearity of the story, the usual image of the river of time, they present the currents and swells of the sea, conserving the trace, the currents and the swells of time.

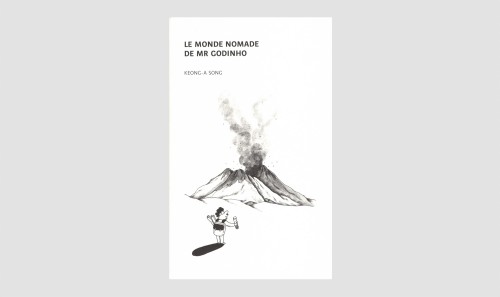

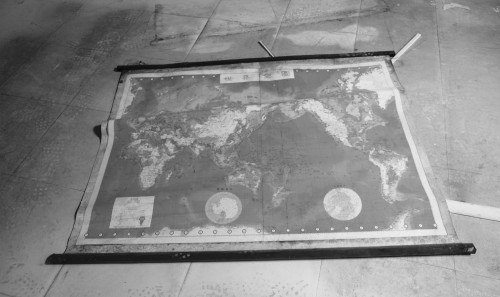

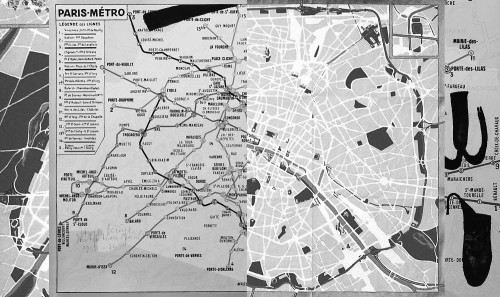

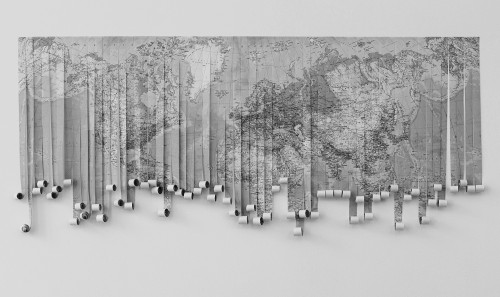

One of Godinho’s earliest works, Calendrier éternel (2006), is subtitled “12 propositions d’espaces pour expérimenter le temps.” That same year, the map motif appeared in his practice in the guise of a manifesto work, Le Monde nomade #1 (2006), for which he had cut a world map into sixty vertical strips, in reference to the division of time into minutes and seconds. These two works prefigured a preoccupation – the interplay of space and time – that has continued to animate the artist’s work, so much so that, in 2015, for the film Et (le dernier dialogue possible), he conceived a dialogue with metaphysical overtones for two fictional characters, Space and Time, questioning their own existence.

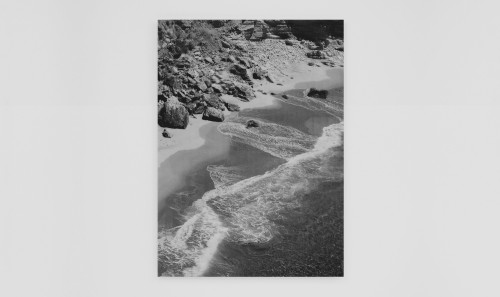

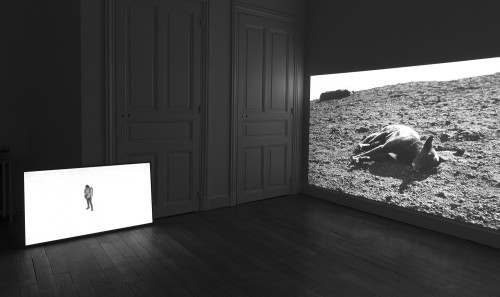

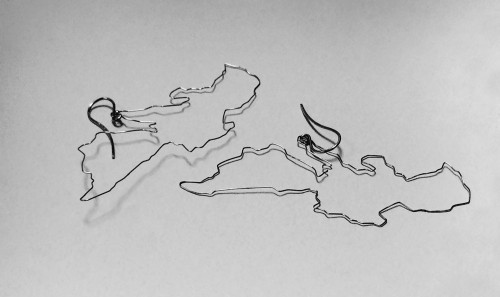

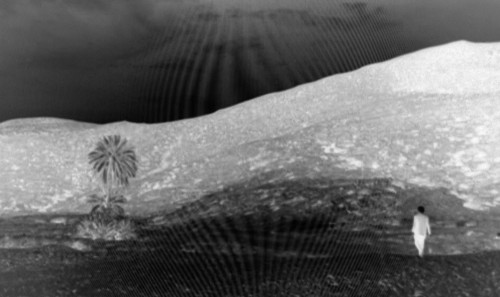

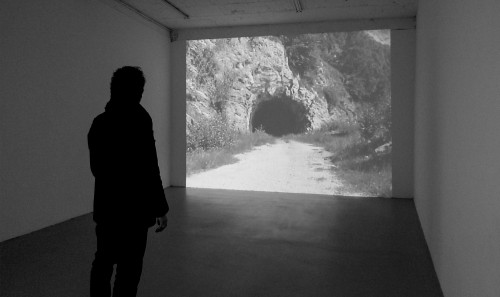

The prism of a cartography of time can also serve to consider Godinho’s interest in frontiers, in liminal areas, in what he calls “landscapes of the edges,” which, he says, stimulate his thinking. “I like to roam geographical limits, the ends of the earth, relentlessly, recklessly, confronting and challenging cartographic conventions. In places where the tension is strongest. … Where things twine together, are made and unmade.” Created on the “edges” of the Mediterranean – a “frontier” that appears several times in his recent-year production – Written by Water is one of the manifestations of this other preoccupation that marks his work. In 2007, for the video Cabo da Roca, he hiked the cliffs of Cape Roca, the westernmost point of continental Europe, and then recreated the vertiginous sensation of the experience in a dual-screen video shot from a subjective point of view. The filmic installation he shot in February 2017 on the slopes of Mount Etna (Notes sur cette terre qui respire le feu (ascension des pentes), 2017) evinces a similarly liminal temporal experience, apparent in scenes such as those where the character, wandering the volcano, appears in the white immensity of the snow-covered crater.

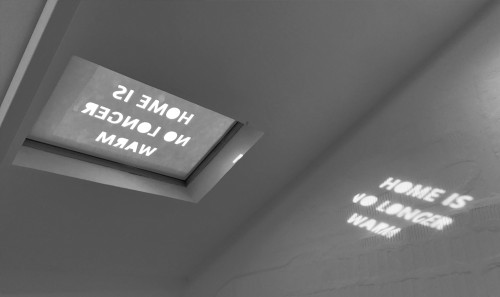

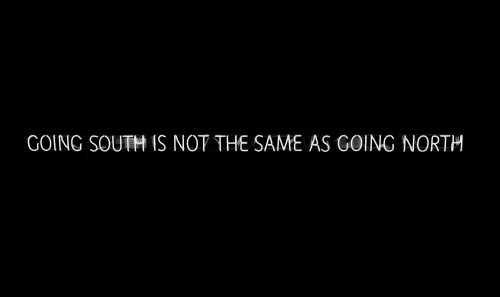

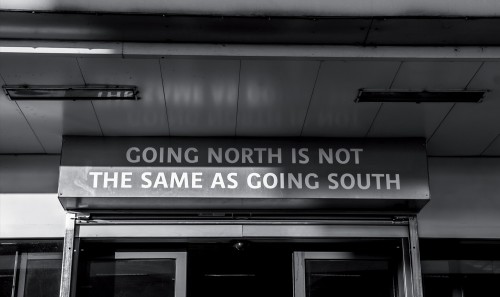

In a similar movement, several of Godinho’s works place our routine gestures and travels on a broader spatial and temporal scale defined by the fundamental forces that govern our understanding and experience of the world. For example, Going south is not the same as going north / Going north is not the same as going south: in 2016, for a collective project in public space, he posted these statements in large letters on vacant signage space above the entrances to two gas stations north of Metz, on either side of highway A31, one of the key transit routes between northern and southern Europe. The north-south axis was also pivotal in his Venetian project, described as an “initiatory journey that would go from north to south, counter to contemporary migrations” He thus addresses both the imagination with which this axis is associated and the political realities of which it has become a symbol.

Writing

Language, words, literature and writing constitute another favourite universe in the practice and imagination of Marco Godinho, who grew up between cultures and between languages. Like the process of translation and the “changes in meanings” it engenders, words in his work represent a force of displacement, of projection in time and space.

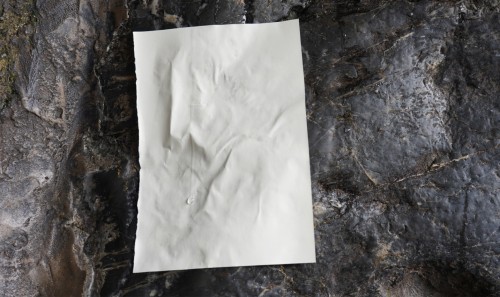

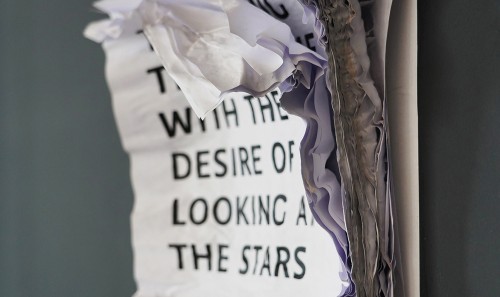

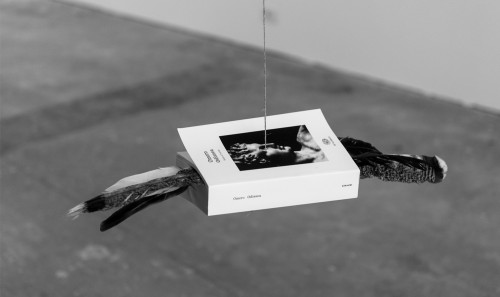

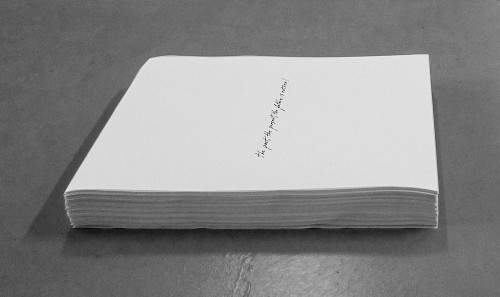

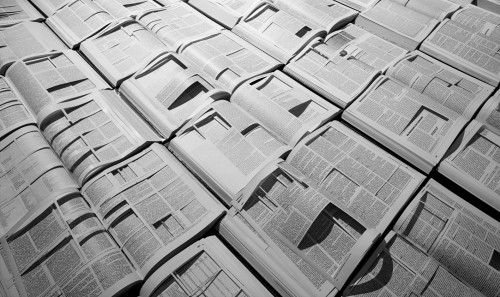

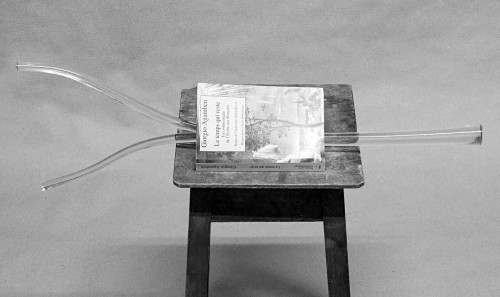

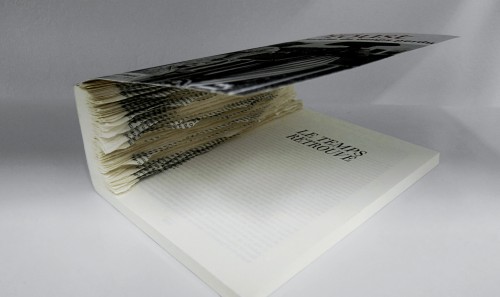

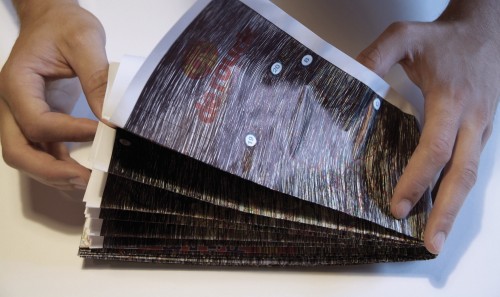

This is seen first in the activity of reading, which the artist has made central in several works. In 2009, with the installation Du temps perdu à la recherche du temps perdu, he offered a meditation on the very temporality of reading and its anchoring in the quotidian. , His ambitious film Left to Their Own Fate (Odyssey) (2019), made for the Luxembourg Pavilion at Venice, echoes Written by Water and proposes a reflection on the work’s relationship to the world, via reading, and on reading’s capacity to activate the past in the present of the experience. In the film, we watch the artist’s brother, the Luxembourgish actor Fábio Godinho, silently read the three volumes of the French translation of Homer’s Odyssey during three voyages made along the Mediterranean coasts: the first in the Strait of Gibraltar, the second stopping at Tunis, Carthage and the Island of Djerba, and the third at Trieste and in the Istria region. Once read, each page was torn out and, in a gesture of offering, abandoned to the sea. In this gesture, there takes shape what Jean-Christophe Bailly calls the “relaunch of meaning”: “Meaning ricochets from the world toward the author, then from the author toward what he writes, then from the composed book toward the reader, then finally from the reader toward the world.”

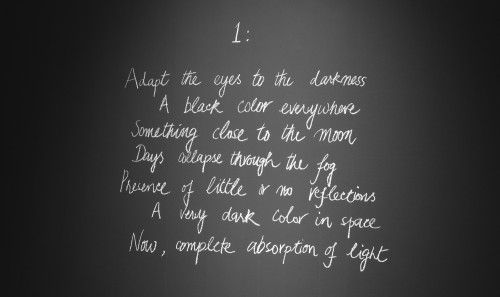

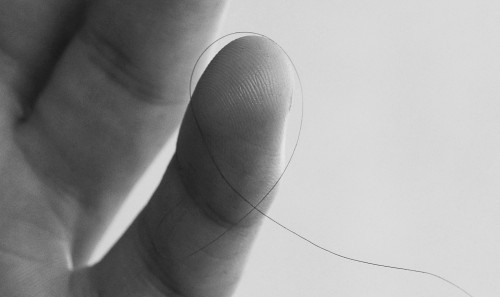

This relationship of language with the world is evident in Godinho’s interest in two specific writing practices: poem composition and note-taking. Both are characterized by their economy of means, their concision of form, the observation, attention and availability they entail, the crucial connection they forge with the real, and their capacity to record and render the vibration of the world. These forms of writing are not confined to works that make explicit use of language; indeed, they span his entire oeuvre. They are found, for example, at the core of a series of videos begun in 2003 and assembled under the eloquent title The Evanescence of Things. The artist compares these short sequences recorded in everyday situations to “notes,” “visual poems,” and “perceptive haikus” in which “time seems to be suspended or denotes a tension.” More broadly, this expressing through writing speaks to Godinho’s desire to maintain his practice in the flow of life. It is the power of the title he chose for his notebooks. Written by Water suggests the idea of a writing that, far from going from the writer toward the world, takes the opposite route; a writing that comes from the world and to which, in a way, it suffices to be attentive. As Novalis wrote, “It is not only man that speaks – the universe also speaks – everything speaks – infinite languages.”

The “broadening of the poem,” as Jean-Christophe Bailly nicely puts it, also serves to explore the place of the poem in our lives, to affirm its receptive and freeing power. Godinho sees in the furtive instants that he calls poems “this tiny time-space that can shatter everything if we pay attention to it.” “It is also the idea of a poem: an eternal beginning, a detonator of possibilities, of openness to the world,” he adds. The instant, the fragment, the “sliver of the present” are the entry points to a far more vast time. Which is what Roland Barthes says of the haiku: “We musn’t be misled by the haiku’s tenuity: in the form of a strict enclosure; it’s the beginning of an infinite speech that can unfold the summer.” It is also what Jean-Christophe Bailly suggests in words which, because they invoke the image of water, because they speak of the white of the page, seem to have been written for Written by Water: “Whereas prose inhabits time like a continuum around which it winds itself, the poem leaps from the timeline. Although unable to escape it as the image can, it takes a step to the side and replaces the unswerving flow or course of time with an internal time that exposes itself in the white of the page. … In hydraulic terms … the poem multiplies the locks, the forebays, the rapids, the waterfalls.”

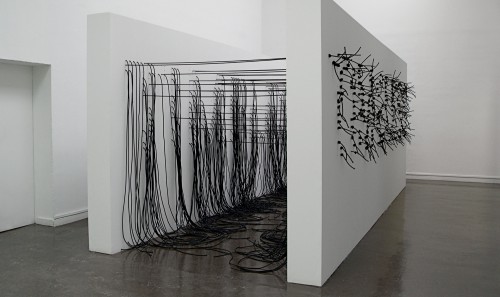

Nomadic Work

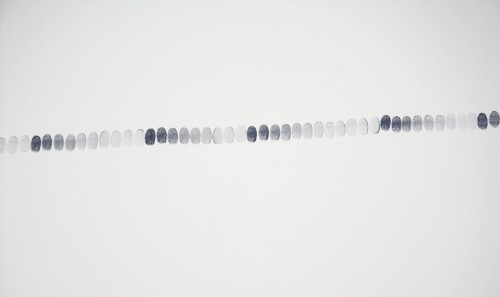

Extending the metaphor, we also could address “in hydraulic terms” the way Godinho’s works manifest themselves in the world. Owing to their often elliptical nature, to the room they afford the viewer’s memories and projections, to the important role of the imperceptible, the invisible, the infra-thin, they elude any overly fixed materiality to explore other modes of being and circulating. They are at once anchored in the present of experience and turned toward a temporal and geographical elsewhere. This is the meaning we gave, in our conversation in 2017, to the idea of “nomadic work.” Forever Immigrant illustrates this notion more than any other piece. Activated numerous times since 2012, it consists of organic forms composed of a single motif repeated myriad times: the mark of a rubber stamp showing, in a circle, the two words of the title: “forever” and “immigrant.” “For every reactivation of the work, I deploy, from this pattern, some forms that are volatile, floating, liquid: a cloud, gas, a wave... This permeability makes, I think, the strength of the work. It is like some water flowing, it can infiltrate several spaces, in several contexts. It is an open form, in transition, passing, permanently evolving, a form one cannot stop.”

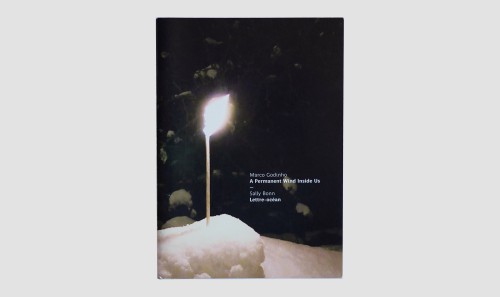

A Permanent Sea Inside Us: this is the title Marco Godinho considered for the Venice pavilion before deciding to extend the notebooks title, Written by Water, to the entire project. “How do we permanently carry inside ourselves the sensitive, life, as it were?” he asks in his working notes. The sea embodies this sensitivity in his work, and we must recognize the full significance of that image. It suggests the idea of a sensitivity which, beyond each person’s imagination and inner world, traverses our innermost selves, links them, connects them – a shared sensitivity. “I do not believe in separation. We are not single,” affirms Virginia Woolf in The Waves (1931). John Donne was of the same opinion in the 17th century, writing in Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions (1624), “No man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.” Even if they are “nothing more than the presence of a vital, sensitive respiration,” the “ghostly invisible writings” of Written by Water offer us this story. They remind us that in each of us there is a part of the sea, and that this immense, intense, moving, infinite sea unites individuals. In this other time of “emergent occasions,” these days of turmoil, this story is essential.

Christophe Gallois is Curator, Head of exhibitions at Mudam Luxembourg.

- Marco Godinho, untitled text on his work, July 2017.

- Marco Godinho, working notes for the project Written by Water, 2019.

- Godinho, untitled text, 2017.

- Marco Godinho, presentation of the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, Casino Luxembourg, June 13, 2019.

- Marco Godinho, quoted in Christophe Gallois, “Nomadic Works - An Interview with Marco Godinho,” Mondes nomads, trans. Anne-Sophie Lecharme (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2017), 72.

- From the poem “Tabacaria” by Fernando Pessoa as Alvaro de Campos, in Selected Poems, trans. Jonathan Griffin (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1974), 111.

- Godinho, quoted in Gallois, 71.

- Chris Marker, liner notes for the CD-ROM Immemory, 1997.

- Godinho, quoted in Gallois, 72.

- Godinho, untitled text, 2017.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The drawing shaped by the “frontiers” of the Mediterranean appears in two recent works: the installation Ecosystem (2016) and, in the unexpected shape of earrings, The Mediterranean Sea as Suspended Territory (2017).

- Godinho, working notes, 2019.

- Godinho, quoted in Gallois, 68.

- Jean-Christophe Bailly, Panoramiques (Paris: Christian Bourgois éditeur, 2000), 18.

- Marco Godinho, quoted in the visitors’ book for the exhibition Out-of-Sync, Les Paradoxes du temps, at Mudam Luxembourg, 2011.

- Novalis, Notes for a Romantic Encyclopedia [Das allgemeine Brouillon, 1798-1799], ed. and trans. David W. Wood (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007), frag. 143, 24.

- Jean-Christophe Bailly, L’Élargissement du poème (Paris: Christian Bourgois éditeur, 2015).

- Godinho, quoted in Gallois, 71.

- Ibid.

- Roland Barthes, The Preparation of the Novel [1978-80], trans. Kate Briggs (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 90.

- Ibid., 35.

- Bailly, L’Élargissement, 56.

- Godinho, quoted in Gallois, 68.

- Godinho, working notes, 2019.

- John Donne, Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions and Death’s Duel (New York: Vintage, 1999), 101.

- Godinho, working notes, 2019.