In Praise of Vagabond Energy

Hélène Guenin

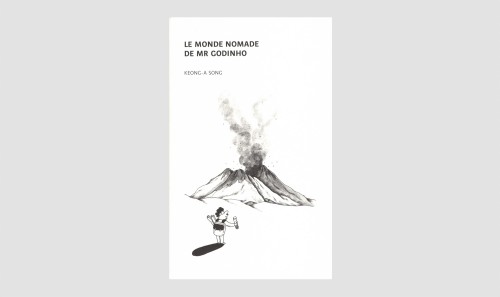

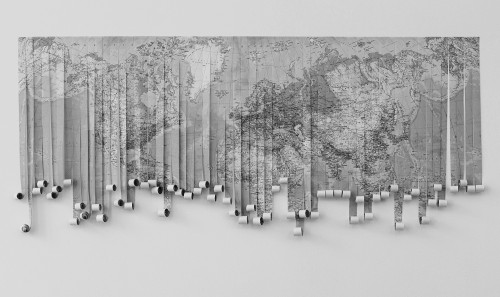

A miniature world …

… lying in the palm of an outstretched hand, carefully rolled up, plucked from a transparent tube.

This is the image that stays with me from my first encounter with Marco Godinho. The nomadic world he evoked that day sparked a glimpse of a commonality of ideas and references, of a certain poetic and political license in the way we relate to the world, to words and, simply, to art, a sharing that over the years has been confirmed.

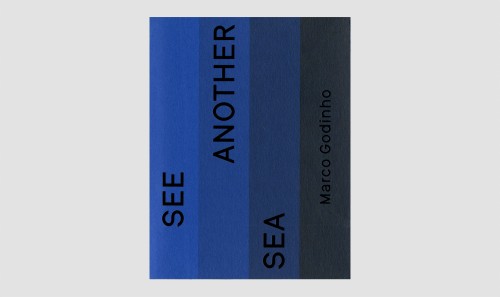

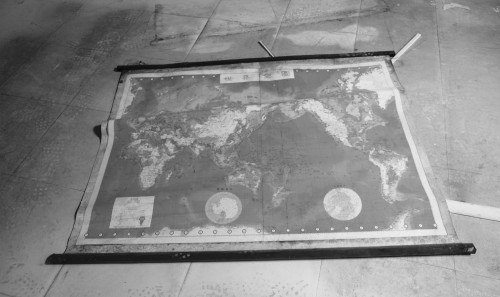

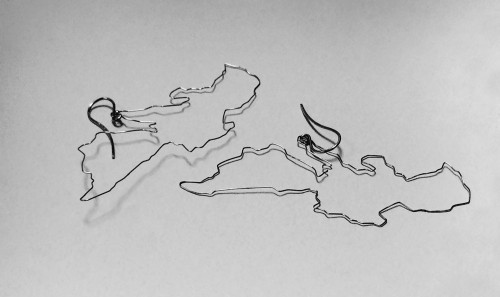

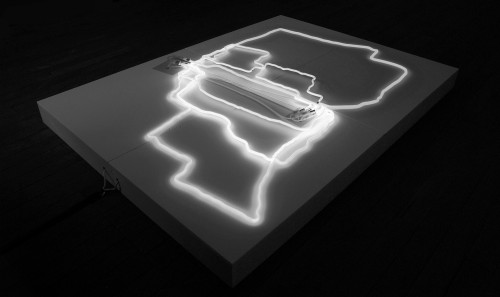

There, already, in the seeming modesty of the vagabond object, lay key dimensions of his work. Divided into sixty strips, this world in transition can be passed from hand to hand in its tube; it can be shown on a wall in its conventional version or reconfigured by interweaving the continents, breaking down borders and upending economic and climatic inevitabilities. From this simple object, the artist conjures a dreamlike vision that simultaneously engenders a call to travel, to the imagination, and arouses intimate reflections on the political issues and consequences of these fictional transpositions. There, too, lay a certain connection to the thriftiness of his art and to what I champion as an ethic of production: working with the world, lending enchantment to that which already exists.

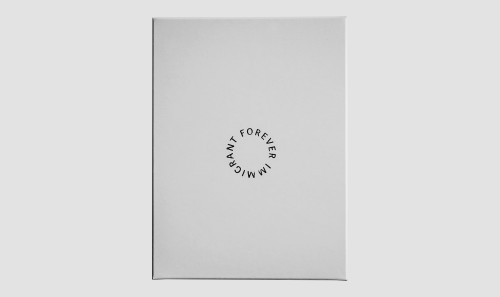

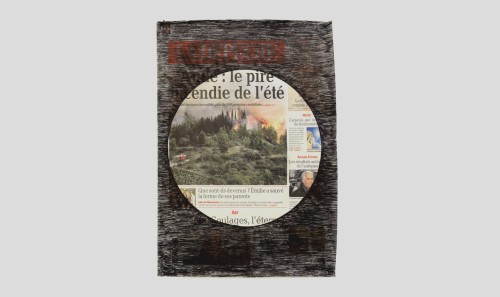

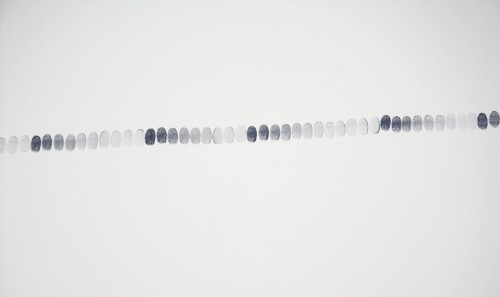

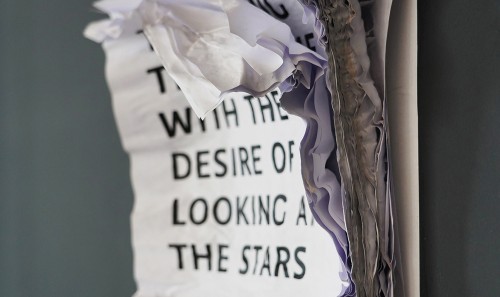

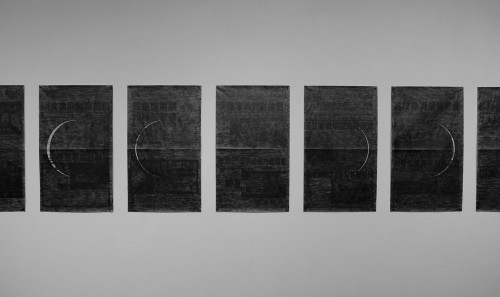

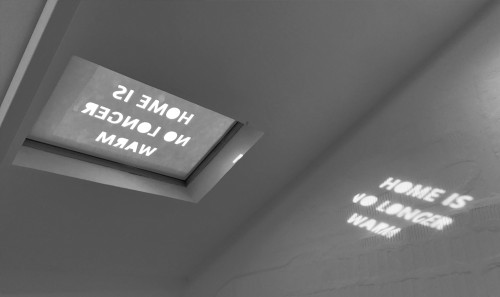

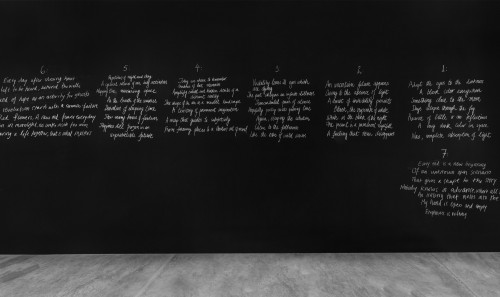

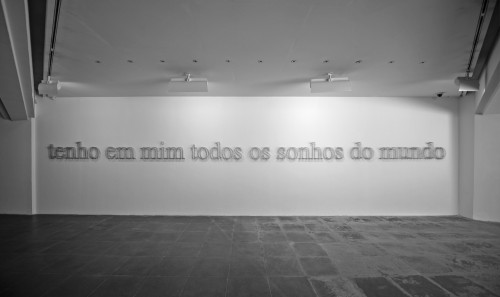

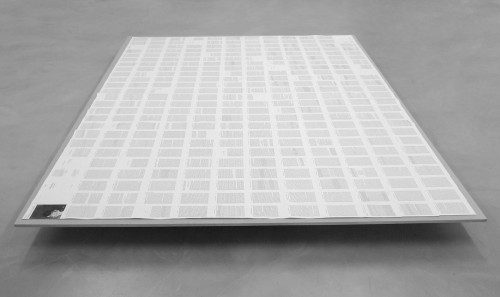

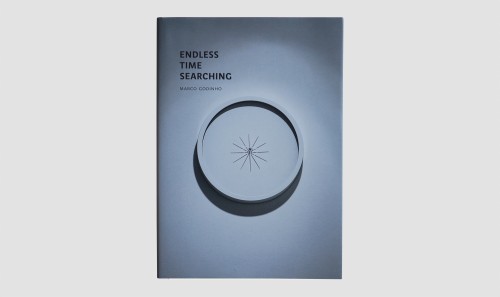

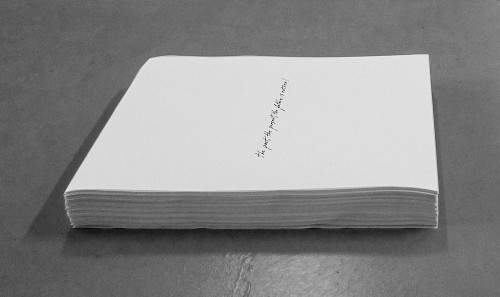

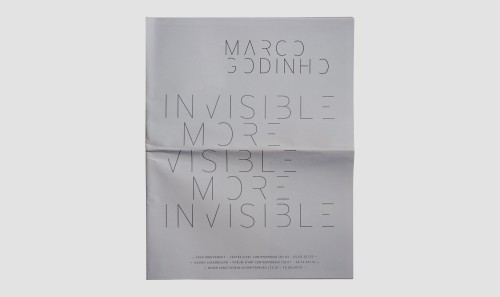

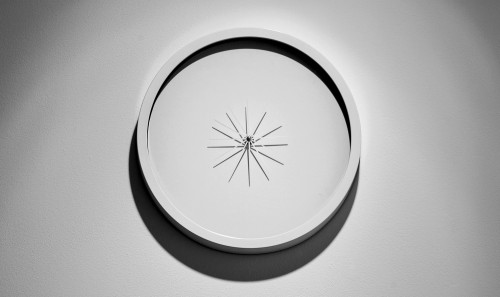

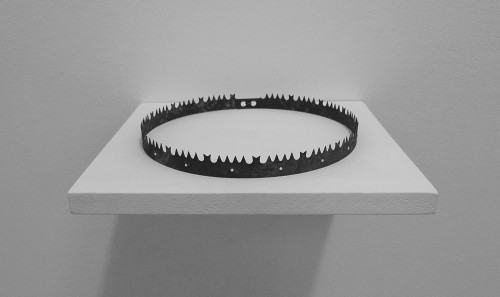

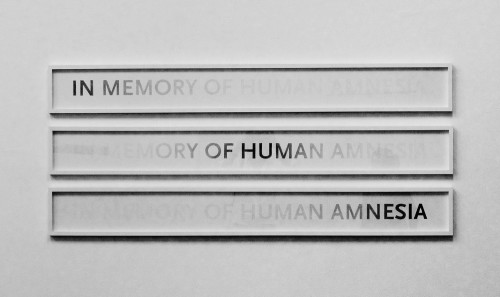

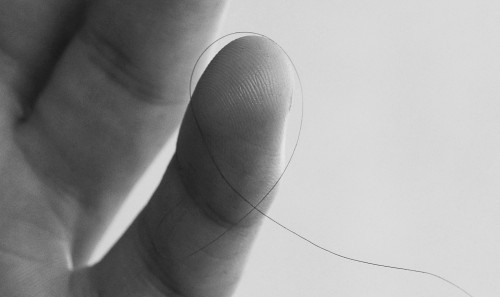

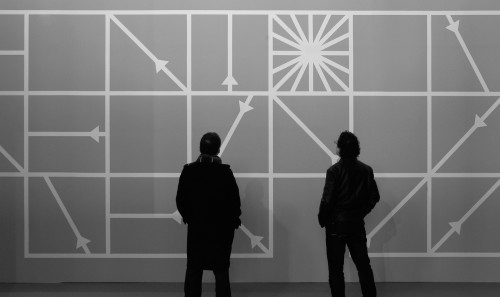

For some years now, this intentional “happy sobriety” or fruitful asceticism has marked his art with thinking gradually honed by the economic and ecological facts of its production. Accordingly, most of his pieces are made from materials recovered or revitalized in the places where he works, following established protocols. Forever Immigrant (2012) is certainly the most striking example. The imprint of a simple rubber stamp bearing a circular inscription around a blank space the size of the artist’s thumbprint becomes an imposing mural, forcefully inked in varying densities on walls, expanding or shrinking according to the size of the designated area. The urgency of the claim or condemnation to exile looms in reading the detail, in observing the singular trace, in the anonymous absence of the suggested fingerprint. The monumentality of this “roaming visa” spreading along gallery walls or the streets of Lampedusa charges it with the evocative power and freedom of a migratory flow, of a flight of swallows, a swarm of bees, of the topography of an island or a mountainous terrain. Somewhere between a memento evoking his personal journey and an anonymous hymn to the millions of other journeys, chosen or endured, the mural discloses its content only to attentive eyes. It reveals the world traveller’s destiny in a whisper: he does not belong to any territory. Immaterial save for the diverted bureaucratic stamp and its ink, this work is a sensitive exploration of the questions of exile, memory and geography. The artist’s reflection on these questions is fuelled by his own experience of nomadic life, caught between multiple languages and cultures and marked by the influence of literature and poetry. Forever Immigrant was also the primer for the initiatory voyage he undertook some years later, following mythological traces of the multicultural and erratic origins of both Mediterranean culture and the burning issue at the heart of his project for the Venice Biennale. In the age-old and contemporary odysseys that he invokes, Godinho traces an “anatomy of restlessness” shared on all Mediterranean shores. Pages in appearance blank, suffused by immersion in the waves with the destinies that have crossed this sea, are presented like an immense anti-monument, a frail continent of stories, in the Luxembourg Pavilion. They all seem to be haunted by the same message: Tenho em mim todos os sonhos do mundo (I have in me all the dreams of the world). This line from the poem “Tabacaria” by Alvaro de Campos, one of Fernando Pessoa’s heteronyms, belongs to the artist’s body of protocol-based work. Produced for the first time in 2007, the eponymous piece is reactivated on exhibition space walls by means of nearly 3,000 carpentry nails meticulously planted to compose a written line at once physical, fragmented, arduous, monumental and modest. The use of nails is not insignificant: it carries the hopes of all those who have left their countries, the harshness of the journey and the wearying quest for a better life. Pessoa led multiple literary lives under other names, creating the unique oeuvre of a traveller with a thousand masks who steps away from himself to better invent imaginary characters. In using this fecund phrase, Godinho celebrates Pessoa’s metaphysical nomadism, his affirmation of the power of inner life.

The poet wrote these lines under his own name:

…

The Distance opened in flower, and the Southern Cross

Shone in splendour over the galleons of initiation.

…

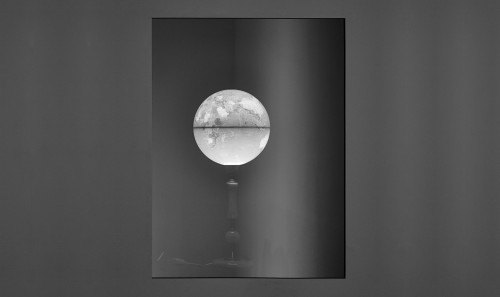

The dream consists in seeing the invisible shapes

Of the hazy distance, and, with perceptible

Movements of hope and will,

Search out in the cold line of the horizon

The tree, the beach, the flower, the bird, the spring …

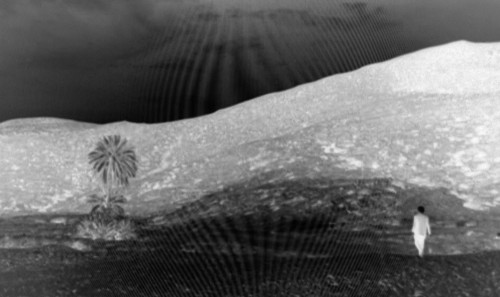

The poetic enunciations of the world, the emergence of dreamed or physical landscapes through the experience of walking, the vagabond works that Godinho brings to life in each new context define the singularity of his approach and stem not from an inconsistent focus but from an articulated relationship to the stories, to life and to his production: a nomad, open to whatever happens, uplifted by the words of a genealogy of world roamers who came before him.

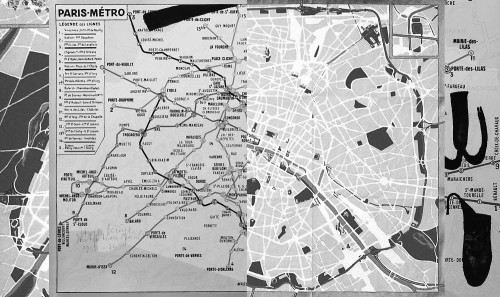

Bruce Chatwin was one of those roamers. He devoted his literary efforts to this question: Why do men wander rather than sit still? From Patagonia to Australia, he satisfied his desire for wide open spaces and his fascination with nomadic cultures and exile. Among other things, he travelled Aboriginal paths in search of a tradition handed down through generations: songs that describe physical and symbolic landmarks in Australia’s vast expanses, oral maps that enable listeners to walk in the footprints of the ancestors. Aboriginals do not imagine territory as a “block of land hemmed in by frontiers, but rather as an interlocking network of ‘lines’ or ‘ways through,’” one told Chatwin. “All the words that we use to say ‘country’ … are the same as the words for ‘lines.’”

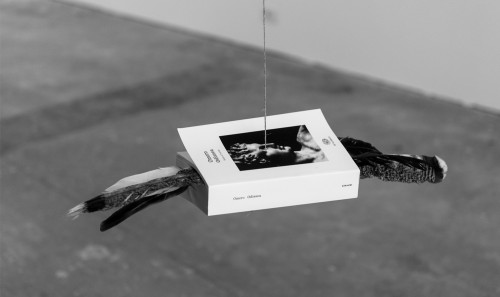

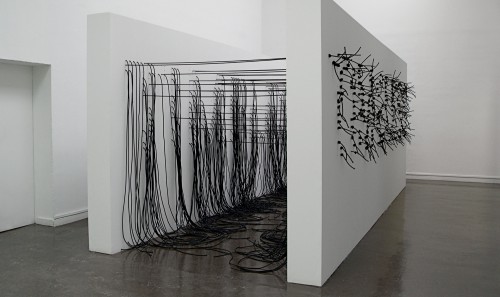

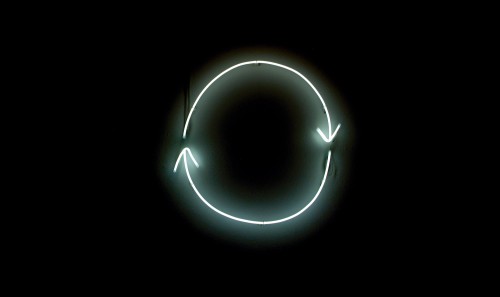

Pathways, memories and chance happenings, lines, individual trajectories. All these things infuse Godinho’s L’Horizon retrouvé. A work in process, solitary or activated by collective contributions, it is a simple knotted line made of strings, cords and shoelaces randomly picked up in streets and on walks. The improbable assemblage of these cast-off and recovered items forms a motley horizon line that runs along gallery walls at eye level or lies rolled up in containers. The artist created it for the first time during a residency in Paris. This 25-meter-long, chance-made work, composed of fragments of abandoned life, is a sort of yardstick of his attentive urban roaming. It reveals the invisible traces and highlights minute and ignored details of daily life, endowing them with new nobility. “It is along paths, too, that people grow into a knowledge of the world around them, and describe this world in the stories they tell,” says the anthropologist Tim Ingold. This knowledge and this story emerge in the silent eloquence of the horizons collected on foot, on the ground, by Marco Godinho.

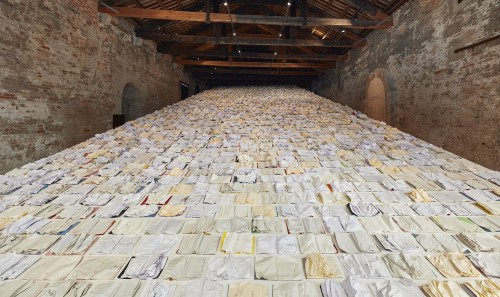

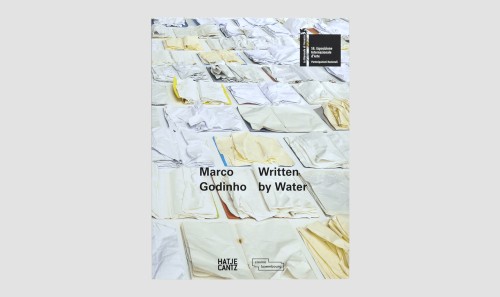

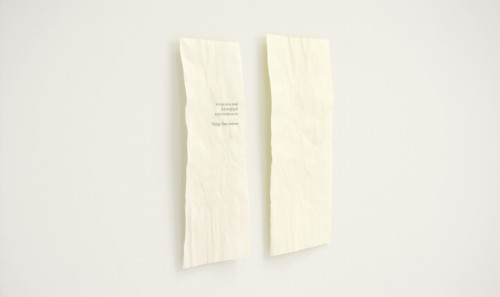

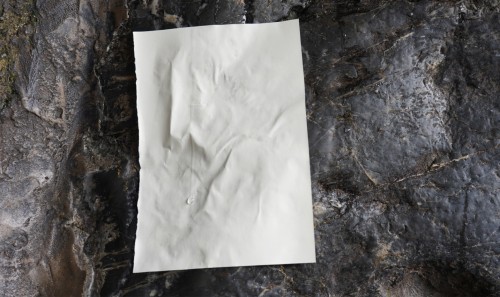

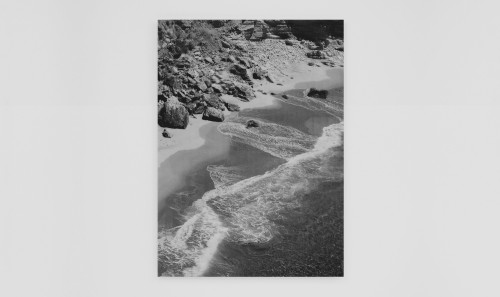

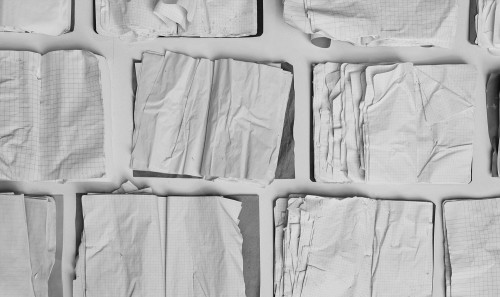

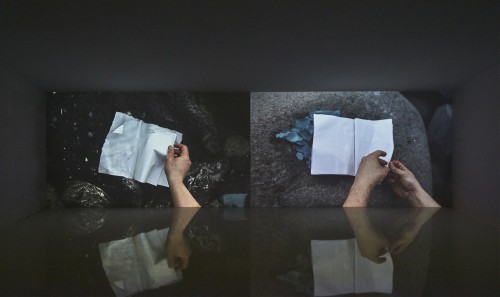

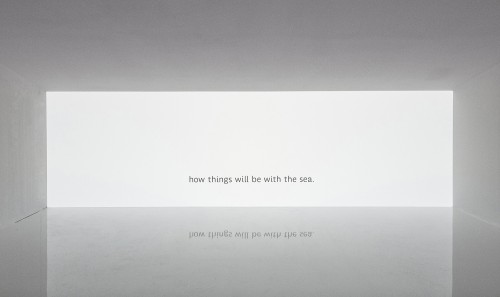

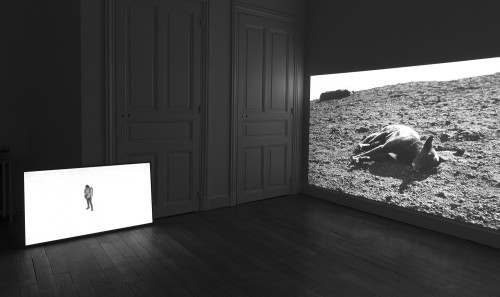

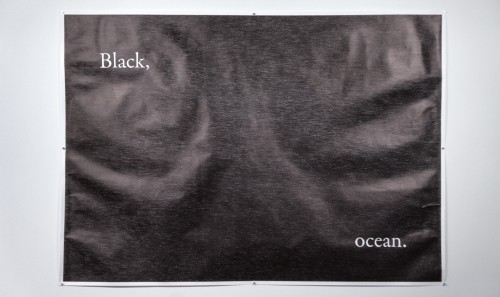

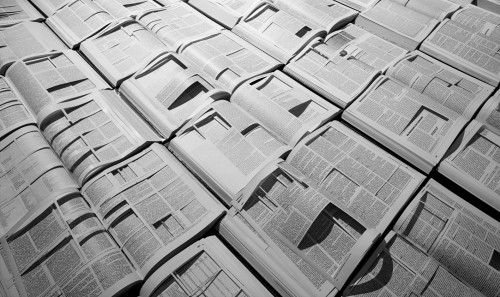

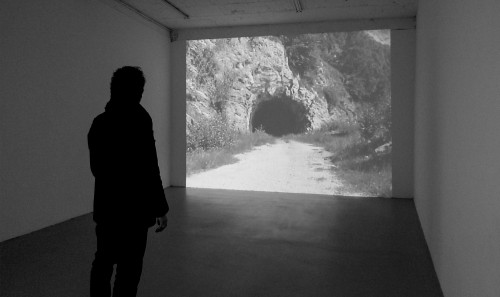

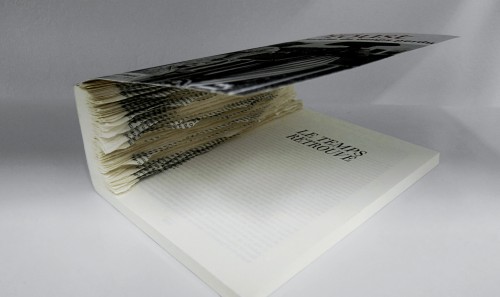

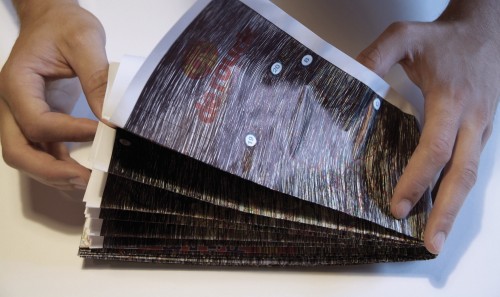

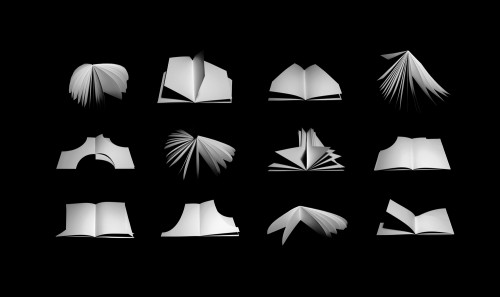

These invisible paths are also embodied in Written by Water, a body of work begun by the artist in 2013 on the European and African coasts of the Mediterranean and assembled like a massive library in the Luxembourg Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The journeys are recounted by the sea itself, bearer of the hopes and tragedies that cross its waves. The artist immersed notebooks devoid of writing in the waters of the cities where he stopped on both sides of the sea. Saturated with the shared waters of coasts whose human, social and economic realities are at once so different and so near, the notebooks took in the wandering destinies. “Of all the elements, water is the most faithful ‘mirror of voices,’” writes Gaston Bachelard in Water and Dreams, borrowing a lovely metaphor from Tristan Tzara. If this supposes the existence of a “rapport” between the voices of nature and the sounds of water, then the hypothesis can be extended to water that carries all the stories of those who enter it. To the water’s memory that fixes its writing, invisible to our eyes, on the blank pages offered by the artist. Paths, seagoing itineraries – all the routes of our journeys rustle with the ancestral memory of humanity’s permanent movements. Just as the mountainous slopes of the Roya Valley, from time immemorial a passageway between South and North, whisper in the footsteps of today’s migrants the fates of the moving populations who took the same paths a few millennia ago. Gabriele D’Annunzio’s words in The Contemplation of Death resonate with foresight in this regard: “The richest experiences happen long before the soul takes notice. And when we begin to open our eyes to the visible, we have already been supporters of the invisible for a long time.”

For the artist, water is also a powerful generator of forms. Here, again, it is not a matter of adding objects to the world’s order but of creating with the elements. Like John Cage, environmentally aware and master of chance, who created the series River Rocks and Smoke (1990) in the wilderness, Godinho works in collaboration with nature. A gesture of humbleness, of creative synergy with the elements, Written by Water updates the process-based art experiments of the 1960s and 70s. The artist’s approach – immersing the notebook, waiting for the elements to “deposit” and the sea to inflect the pages – is close to the Oriental philosophy that teaches respect for nature. This attitude leads to simply revealing that which is and fostering continuity with it.

As he explores the forces and materials at work in the visible and invisible world, Godinho subscribes to a form of animism by conveying the story of the water’s possible voices. He also demonstrates an – ostensibly modest – affinity with the weighty issues of contemporary ecological debates. Altering the course of nearly two centuries of profound transformation of our ecosystem, of a utilitarian relationship to nature seen as a mere resource and not as a partner, a generous host whose heartbeats we must listen to, whose rhythm we must respect. Leaving the parasitic relationship to return to the symbiotic bond that still existed a few generations ago and which, in some indigenous cultures, continues to constitute the everyday horizon of living together. Working in “co‑birth,” as Michel Serres expresses his wish, “no more war to the death, rather exchanges of reciprocal services,” conceiving non-invasive gestures instead of pursuing the arrogant stance of world-shaping and the accumulation of monument objects.

Marco Godinho travels light, with no logistics other than his own roaming. Part of his work fits in a suitcase and re-emerges from context to context in the shared energy of collective re-creation. Open to explored territories, to encounters, to whatever happens, in the fertile, febrile, harried margins of the Mediterranean. Moved by the epic spirit of age-old storytellers to convey, with neither pathos nor literality, the beauty and torment of this common heritage.

Hélène Guenin is the director of Musée d'Art Moderne et d'Art Contemporain (MAMAC), in Nice.

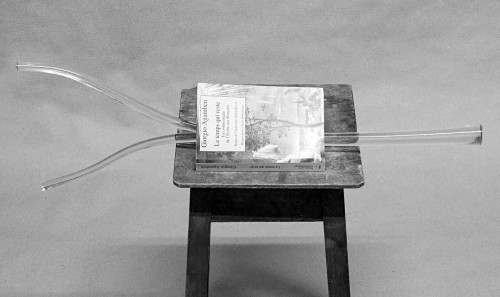

- Le Monde nomade #1, 2006.

- Bruce Chatwin, Anatomy of Restlessness: Selected Writings, 1969-1989 (New York: Viking Penguin, 1996).

- Fernando Pessoa, “Horizon,” in Mensagem/Message [1934], trans. Jonathan Griffin (Exeter: Shearsman Books, 2007).

- Bruce Chatwin, The Songlines (New York: Penguin, 1988), 56.

- L’Horizon retrouvé (Paris), 2013-14. This protocol-based work has since been reactivated in different places and on collective scales.

- Tim Ingold, Lines: A Brief History (Abingdon: Routledge, 2007), 2.

- Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter [1942], trans. Edith R. Farrell (Dallas: Pegasus Foundation, 1983), 193.

- Gabriele D’Annunzio, cited in ibid., 16.

- Michel Serres, Biogea, trans. Randolph Burks (Minneapolis: Univocal, 2012), 170.